Part 2 – Leveraging Privilege

I recognize that I live a privileged life. I am white, was raised in a middle class family, and had my college costs covered. I could go on, but suffice it to say that there are numerous factors I recognize (and probably many more that I don’t) that have given me an advantage in modern American society. That being said, I was also raised with the understanding that it is my responsibility to use my position to lift up others who haven’t had the same advantages.

Noblesse Oblige or White Savior?

I’ve been fortunate enough to build a career I love in the nonprofit world focusing on the concept of social equity, working to address the social determinants of health in both urban and rural settings. However, I still feel like I could be doing more to help others, particularly given more pressing current issues. (A person of color recently reminded me that I am showing my privilege by describing what has been an ongoing issue for black communities for generations as “current events.”)

My last job focused on housing inequality in minority/low-income neighborhoods in Pittsburgh, and therefore put me in the position to listen and learn about issues that many black Pittsburghers face. However, I wouldn’t say I’ve put in much time on my own to learn about issues of race throughout America’s history. For example, neither Christian nor I had heard of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre[1] until a few months ago when we watched the TV show “Watchmen,”[2] which opens its first episode on that event. (While watching the show, I Googled “Tulsa 1921” out of curiosity, and we were horrified that we had never learned about it in school.)

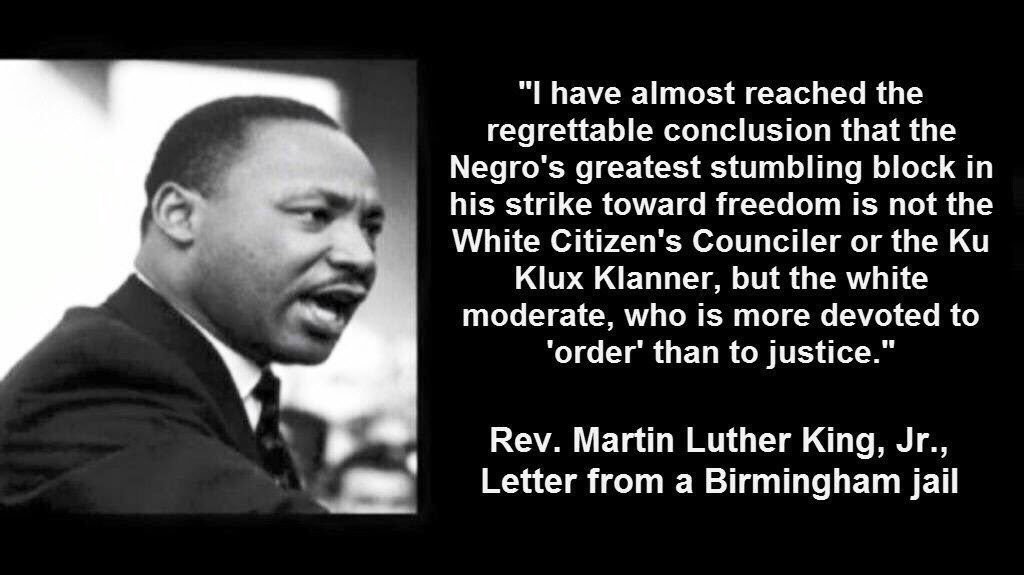

I realize that I fall into the realm of the “white moderate” that Dr. King described in his letter from the Birmingham jail.[3] While I certainly don’t value order over justice, I do recognize that I share some responsibility for my silent complicity. I want to bring an end to that silence – my own and maybe others’ if I can. However, I realize the inherent problem in getting privileged people to discuss their privilege (and yes, I’m going to generalize here): we (or at least I) feel some level of guilt and shame over that position of power. It takes a lot of courage to talk about personal shame, and unfortunately, that reluctance to talk perpetuates the problem. I hope to begin down that path with what you’re about to read about personal exploration of my biases.

Image credit: [4]

As I mentioned in last week’s post, a friend of mine is running a “White Fragility”[5] discussion group for her job at a local university and decided to host a parallel group for her friends. We had our first session this past week, and I was surprised by how much time we took to set up a safe space for discussion, and (despite that step) how many people still seemed hesitant to discuss their privilege and learned biases (with other white people, in a safe space).

As DiAngelo explains in the book, many of us grow up learning about racism as a binary system of good vs. bad. And from that learning, we can easily conclude that “I am not a bad person, therefore, I am not racist.” She says that “we are taught that to have a racial viewpoint is to be biased,” and since racial bias is a bad thing, we don’t want to recognize or admit that we all have it. She continues: “unfortunately this belief protects our biases because denying that we have them ensures that we won’t examine or change them.”

Growing up White

Homework for our discussion group involved examining my own past to tease out what messages I learned about whiteness and when. This exercise was more difficult than it seems because it involved exploration of messages about race in popular culture and products, as well as what we were told by our teachers and parents.

I honestly don’t remember much thought about race as a child. I lived in a white neighborhood and went to a white school. There was a playground across town that I wasn’t allowed to go to, but I wasn’t sure what made its location a “bad neighborhood.” White was a non-issue because almost everyone I knew was white. It was normal; it was standard. I had a few minority friends, but they were mostly Asian minorities, and they (as individuals) were generally bright and came from wealthy families.

Image credit: [6]

My hometown has a large Puerto Rican community, so the middle school I attended was (based on my recollection) approximately half white and half Hispanic. I remember my friends and I were afraid to start school there because it was a “bad” school in a “bad” part of town. I don’t actually recall much in the way of overt narratives related to race during those years, but my experiences there helped create my personal biases. While my middle school academic classes remained largely white (like in elementary school), there were now lower-track classes full of predominantly Hispanic students. As we were divided by academic ability, race and class lines also seemed to track with those divisions.

While we were still constantly told by our teachers that everyone is equal, and we should treat everyone the same, middle school was the first time I remember thoughts that included “us vs. them” style narratives. I began to draw connections between race and things like academic ability, interest in the arts, polite behavior, and affluence. Later on, high school honors classes, orchestra, and French club reinforced those beliefs even more, and then I went off to a small, private, expensive, white, liberal arts college in New Jersey.

The White Moderate

What’s the best way to educate a bunch of affluent, white kids about systemic racism? My college offered electives and special events about multiculturalism, which I don’t believe do much for people who don’t want to recognize their own privilege. Sophomore year I attended a panel discussion on campus one evening about slave reparations. My jaw dropped as real Black Panthers walked into the hall. My boyfriend (not the one who sang “Avenue Q” with me – a different one) was taking notes for his blog during the discussion, and I can still remember watching him write in all caps and underline the words “I AM INNOCENT!”

Are we “innocent”? No one I know personally has ever kidnapped human beings from their home continent and forced them into slavery. No one I know personally has ever committed hate crimes. My dad’s family lived in the south before the Civil War and some of them likely fought for the confederacy, so I’ve got that connection. But the aforementioned boyfriend’s family came to America in the mid-20th century and had no connection whatsoever with the Civil War.

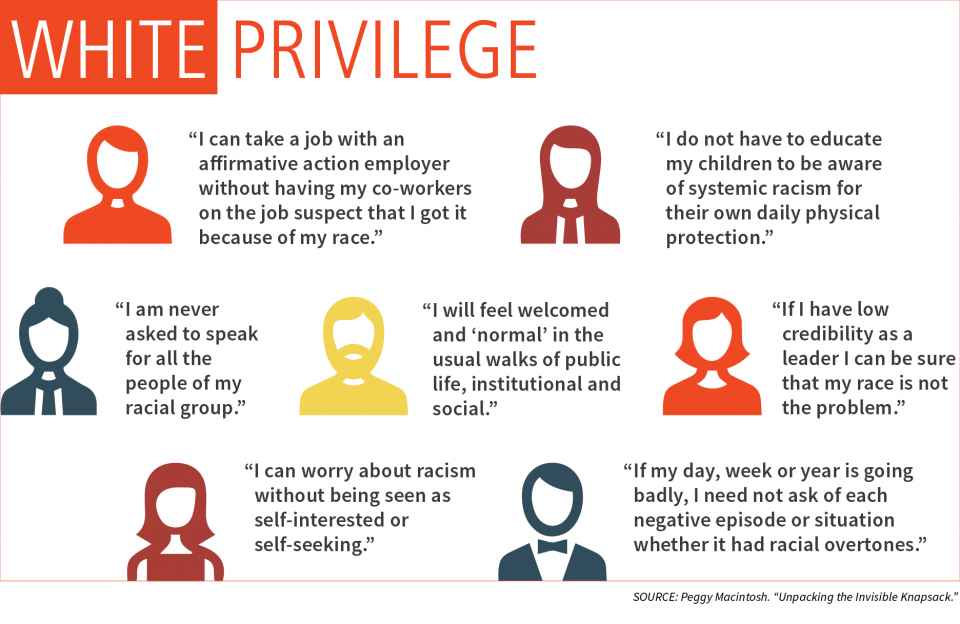

Image credit: [7]

Based on those facts, it’s arguable that I would have more responsibility than he for making things right. But regardless of our ancestors’ involvement (or not) in the support of slavery, he and I were both unknowingly benefiting from larger cultural biases that labeled us as intelligent, cultured, and high-potential; biases that I now realize I learned in middle school (or possibly earlier).

If we’re defining “racist” as someone who shouts slurs and actively claims hatred of other human beings based on the color of their skin, then no, I know few, if any, racists. (And if I do, they know to hide it around me.) But if we’re talking about racism as a set of learned biases that fly just under the radar, then yes, I am, and everyone I know is. So my question is: what can I do about it?

Getting Involved

DiAngelo suggests that we ask ourselves not if we are racist, but rather ask ourselves whether or not we are working to interrupt racism in a given situation. As I mentioned last week, my first step in doing that is becoming more educated on the history of racism, particularly racism in America.

My second step is supporting organizations that are doing work nationally, regionally, and locally to support justice and a more equitable society. To that end, I have provided a well-researched (not by me) list of organizations that are doing good work to address root causes more than acute symptoms. Each one of these groups could use financial support if you are willing and able. As always, I encourage you to do research on your own before donating. You can find more detail on each of these groups in this article from Vox [8], but the list below includes links to the sites directly:

Large network that re-grants donations where needed

- Donations to Movement For Black Lives through ActBlue

National and regional organizations

- Black Voters Matter Fund

- Showing up for Racial Justice

- National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls

- Survived and Punished

- Fund for Black Newspapers

- Highland Center

- JustLeadershipUSA

State and local groups doing movement-building and organizing work

- JusticeLA (Los Angeles)

- Bread and Roses Community Fund (Philadelphia)

- Voice of the Experienced (Louisiana)

- Southsiders Organized for Unity and Liberation (Chicago)

- Equity and Transformation (Chicago)

- The Crossroads Fund (Chicago)

- Texas Organizing Project (Texas)

Restorative justice, violence interrupting, and other large-scale transformation groups

- Life Comes From It

- Spirit House

- National Black Food and Justice Alliance

- Community Street Team (Newark, NJ)

- H.E.L.P.E.R. Foundation (New York City)

- LIFE Camp, Inc. (New York City)

- National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform

- The Professional Community Intervention Training Institute

…and one more on restorative justice, recommended by a reader: International Institute for Restorative Practices

Electing more progressive prosecutors

I try to provide as much comprehensive information as I can in this blog, but I recognize my own limitations and invite you to add resources and links below (for my benefit as much as for other readers’). We are all learning and working our way through a difficult subject. As always, I welcome discussion below, but please remember to be respectful as we learn and grow.

Thank you for reading.

[1] https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/tulsa-race-massacre

[2] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt7049682/

[3] https://www.africa.upenn.edu/Articles_Gen/Letter_Birmingham.html

[4] https://medium.com/@luqmannation/hillary-rosen-the-democratic-establishment-are-exactly-the-white-moderates-king-warned-us-about-fd507d81b891

[5] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/43708708-white-fragility

[6] https://www1.lehigh.edu/housing/buildings/umoja-house

[7] https://www.mankatoywca.org/concepts-racial-equity

[8] https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2020/6/9/21281538/how-to-donate-to-black-lives-matter-charity

2 Comments

Lisa Moriarty · June 22, 2020 at 6:12 pm

Wonderful very very important

Ty Allison

Alison · June 23, 2020 at 9:06 pm

Thank you Lisa!