Part 1 – Admitting it is the First Step

Princeton: You’re a little bit racist. / Kate: Well, you’re a little bit, too.

– “Avenue Q”

Princeton: I guess we’re both a little bit racist. / Kate: Admitting it is not an easy thing to do…

Princeton: But I guess it’s true. / Kate: Between me and you, I think

Both: Everyone’s a little bit racist, sometimes.

Doesn’t mean we go around committing hate crimes.

Look around and you will find, no one’s really color-blind.

Maybe it’s a fact we all should face.

Everyone makes judgments… based on race.

My college boyfriend and I spent most of senior year singing the score of “Avenue Q” together.[1] I loved how edgy it was – like Sesame Street for adults – covering such jaw-dropping topics as homosexuality, loud sex, internet porn, interracial relationships, and racism in America. Upon recent review, I can’t say that all of the lyrics have aged with the times, but I will always credit it with being the primary reason I readily admit my own racism.

Accepting Racism

For the fifteen or so years or so since I learned every word of this musical and was awoken to the fact that I have inherent racial biases with which I was raised, I haven’t been quite sure what to do with that information other than work actively to recognize when my decisions are made based on fact or on personal bias. I have also long believed that since I was born into a life of resources, stability, and privilege, that it is my responsibility to lift up others who have not had the advantages I’ve had, whether racial, economic, or educational. Again, when it comes down to how to do that, I feel like I’ve never been quite sure of the best course of action, though social equity is something I have tried to focus on supporting in my career path. But ultimately, I don’t consider myself to be very progressive, and I feel like I could be doing more good with my position of privilege.

The events of the past few weeks and months have been incredibly disturbing and have really shone a spotlight on the systemic racism in our country and biases baked into our law enforcement and criminal justice systems. On one hand, it has been horrifying simply to turn on the news; on the other hand, it has also been heartening to see the sheer scale of voices from communities of color and support from white allies calling for justice and accountability. When I “look for the helpers,” as Mister Rogers taught us to do,[2] I see ways I can educate myself and work toward the change I want to see in the world.

Image credit: [3]

Friends of mine have been sharing information online about how to contribute time, money, information, and physical presence in a variety of ways (and I will be providing a list of resources and ideas below and in the coming posts). One opportunity in particular that caught my eye was from my dear friend Kelly who is leading a discussion group on the book White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism.[4] I signed up immediately.

One friend I told about this group was surprised that I signed up for it because she does not consider me to be a “fragile white person” – because, she told me, I do recognize my privilege and take steps to fight for social equity. I hope her assessment of me is accurate, but I also believe that we can all do better. And my goal in joining this group was to learn how I can better engage others in these types of conversations, particularly those who aren’t as willing as I am to talk about race.

Minority Voices

Since we’re going down this path, I feel the need to say that I recognize it is not my place to speak for minorities. It is not my time to be center stage, but to be a good ally by supporting others’ voices and highlighting their experiences. However, I am becoming rapidly aware that many of us in the majority don’t know how to do that. I think that part of the problem with talking about race in America today is not only the fact that we aren’t taught how to talk about race, but that most of us don’t have the first idea of what it is like to be a minority. Therefore I’m going to go on a tangent about myself to demonstrate how little I understand about being a person of color in America…

I had an interesting conversation recently with my friend Katie about our time living in Japan.

In relating details of this conversation, I do not mean in any way to speak for communities of color, nor do I mean to imply that I know what black and brown Americans are going through. I don’t.

I did, however, get an experience that many white Americans will never know: I got a peek at what it is like to be a minority, whose every move is watched, who is expected to be a token representative for one’s entire culture. And while I ultimately loved my time in Japan and wouldn’t trade it for anything, I could never quite put my finger on why at the end of it I was so emotionally exhausted and ready to leave my little town in the mountains.

I can’t even imagine what it’s like to be a minority in an unwelcoming society.

For the two years I lived in Japan, the level of scrutiny visited upon each one of my actions or decisions was a source of low but chronic stress for me. I was expected to learn the culture and adhere to norms – and I did – but I knew that no matter how hard I tried, I would never be accepted as part of the group. I felt that I had the responsibilities but not the benefits being part of Japanese society. And I think the knowledge that I would never not be a gaijin (literal translation: “outside person”) was what ultimately broke my spirit and told me it was time to leave.

No mistake, I was absolutely welcome there, but I was, in the end, a novelty. Levels of discretion and privacy afforded to Japanese people were not afforded to me. People knew what I had bought at the grocery store the previous evening, when and where I went running, if my computer got a virus, my weight and how my body was shaped – all of these were topics of conversation, and nothing was off limits. Kindergarten boys and elderly men alike made comments about wanting to touch my large breasts, as though I had no bodily autonomy. Sometimes it just happened, without even the pretense of asking. (In the years since, I’ve watched people there touch my husband’s chest and stomach without permission – because he’s shaped differently from most Japanese men.)

I can take a step back now and know that I received this incomprehensible level of attention because I was different, and they were curious. But during that time in the spotlight, I felt somewhat diminished, flattened to two dimensions. I was, in a way, reduced to the sum of my actions and statements … and then oddly stretched to the sum of all white people’s actions and statements. If, heaven forbid, another white person who lived hours away broke a law, chances were I would hear about it, and my coworkers would want to know if I knew him, and if we all did that. By the end of those two years I felt like I had lost some of my personhood.

But it was only two years. I cannot begin to imagine how I would have responded if I had lived there over a longer period of time, or if I had been raised from childhood treated that way. And furthermore, they brought me there because I was different; they wanted me to teach their children about the English language and American culture – being different was how I brought value. I cannot begin to imagine being a minority in a situation where I was not formally welcomed, but actively shunned.

First Steps

And that’s where I am now – thinking deeply about the incredibly cushy life I led for two years, in which my biggest sources of stress involved constant time in the spotlight and generalizations about my race – and how, as stressful as that was for me at the time, it is a drop of water compared to the ocean of 400 years of racism, classism, profiling, injustice, police brutality, segregation, violence, and slavery that we as white people can’t even bring ourselves to talk about. So let’s talk about it.

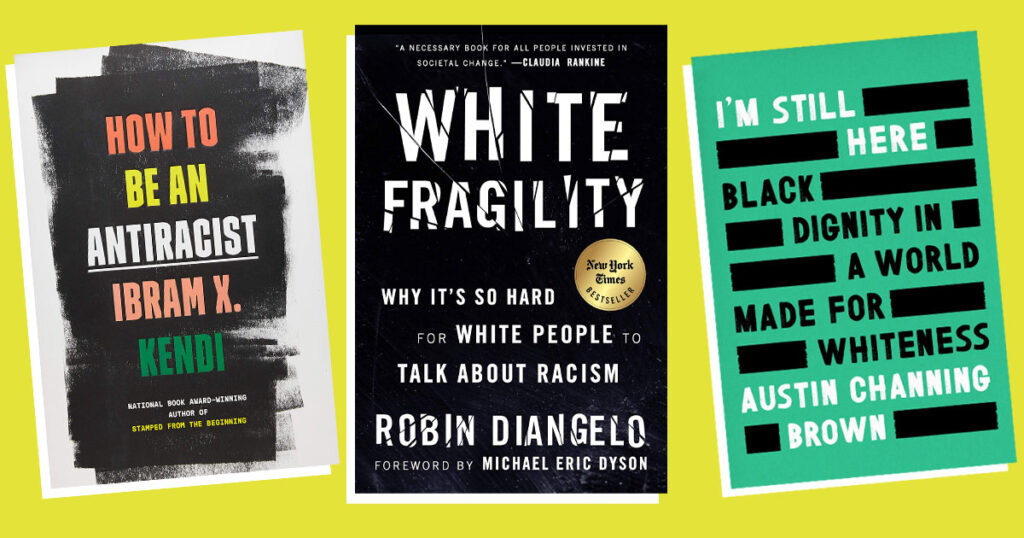

Image credit: [5]

The first step in having an educated discussion on a topic is making sure that you yourself are educated. Fortunately for me, that involves something I love: reading. There are a number of books available that can help educate me and people like me (by which I mean politically-moderate white people) about the history of racism in America and put events in their proper context. The list below, compiled by a white mother of black children,[6] is a good place to start:

- I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness, by Austin Channing Brown

- White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, by Robin DiAngelo

- An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

- How to be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. Kendi

- The Making of Asian America: A History, by Erika Lee

- So You Want to Talk About Race, by Ijeoma Oluo

- An African American and Latinx History of the United States, by Paul Ortiz

- The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America, by Andrés Reséndez

- Me and White Supremacy: Combat Racism, Change the World, and Become a Good Ancestor, by Layla F. Saad

And one more book suggested by a reader: Beyond the Whiteness of Whiteness by Jane Lazarre

Next week I will talk about my own steps down this path, which include educating myself, meeting with my discussion group, and supporting organizations doing good work.

~

Have you read any of these books? What were your thoughts? I’d love to hear what you have to say on this difficult but important topic.

Thanks for reading.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avenue_Q

[2] https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/198594-when-i-was-a-boy-and-i-would-see-scary

[3] http://www.tucsonsentinel.com/arts/report/102212_avenue_q/avenue-q-hilarious-raunchy-sesame-street-parody/

[4] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/43708708-white-fragility

[5] https://www.scarymommy.com/stop-asking-people-color-explain-racism/?fbclid=IwAR3TIu2HlxBrUsK2nuH_t8JJj2z4100bUB8eBlaFtqCWDKF6kGj57LbddjQ

[6] https://www.scarymommy.com/stop-asking-people-color-explain-racism/?fbclid=IwAR3TIu2HlxBrUsK2nuH_t8JJj2z4100bUB8eBlaFtqCWDKF6kGj57LbddjQ

5 Comments

Galen Osby · June 14, 2020 at 10:22 am

I caught part of NPR’s “Only A Game” yesterday, where they interviewed Penn State Professor and “Burn It All Down” podcast co-host Amira Rose Davis, Professor Kenneth Shropshire, CEO of the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University, and the Washington Post’s Kevin Blackistone. At one point, one of them mentioned that if as black people, they could have ended institutional racism and discrimination, they would have done it sometime in the last 400 years, but they can’t, so white people have to step up and help. It raised the question for me of where are the lines between supporting vs being on the forefront and listening vs speaking out, and when is appropriate to do each? I don’t know what the answers are.

Here’s a link to the episode.

https://www.wbur.org/onlyagame/2020/06/12/bonus-podcast-black-lives-matter-sports

Alison · June 14, 2020 at 10:41 am

Thanks Galen for sharing the link. I look forward to listening to it.

As to your question, I may feel differently after the discussion group starts tomorrow, but at the moment, my impression is that the lines between supporting vs. standing at the front and listening vs. speaking out are fuzzy and more of a progression of actions than a choice between discrete actions. Again, I’m still learning too, but I would think that speaking out (while something one could choose to do immediately) can be made more effective through first listening and learning; that standing at the front and knowing how best to do that can be informed by first supporting and learning from those who are already doing it.

Ultimately, I feel like many of us can be doing more than we currently are – I know I fall into that category. It may involve big leaps or baby steps, and that is going to vary by each individual’s ability to share time/money/attention/energy.

That’s my way of saying I don’t know either… yet.

John Rothschild · June 16, 2020 at 1:19 pm

I’m so angry after reading this, that I’m hesitant replying. But here goes. So black people couldn’t end institutional racism? Well, ripped from their homes by slave traders, brought over in chains below ship and sold into slavery. Great start for ending institutional racism. When were the slaves freed? What did that actually achieve? When did the civil rights movement grow. What did that actually achieve? Where are we now? And, oh my God, the Black people still haven’t ended institutional racism or even discrimination! Where does racism and discrimination against Blacks emanate from? WHITE PEOPLE, duh. And there is the idiotic comment that white people need to step up and look for lines to step up properly?! My mind is hurting listening to this.

Galen Osby · June 16, 2020 at 8:23 pm

I’m sorry, but I’m not clear on what your saying. Could you please clarify?

Galen Osby · June 16, 2020 at 8:53 pm

*you’re