As I’ve mentioned many times in many situations, I am frequently crippled by analysis paralysis – the state of having too many options from which to choose and too much information to make use of in order to arrive at the “right” decision. In other words, my perfectionism runs rampant, and I can’t get started. On the occasions on which I can start a project, I often can’t finish it – because achieving a state of doneness that does not reach a state of perfection is something I also cannot handle.

Ironically, one sizeable project that has plagued me (and my perfectionism) for several years is my garden – something that is supposed to be natural, i.e. not perfect. That being said, I grew up looking at stunningly beautiful gardens that were designed by my aunt, who is an artist and horticulturist who owns a garden center.[1] Therefore, I also have incredibly high standards and expectations for what gardens can and should look like, and – not having my aunt’s encyclopedic knowledge of plants or artistic ability – have had difficulty designing something that satisfies my standards.

Getting Started

For those not crippled with perfectionism like I am, there are several things to keep in mind when planning a native pollinator garden, most notably that you should be selecting plants that are native to your region and that represent a variety of shapes, sizes, colors, and bloom times throughout the season (early spring through late fall). You should also be planting each type of plant in groups of at least three so it’s easier for pollinators to gather pollen and nectar from them when they’re in bloom. [2]

I wanted to design something artistically perfect that had beautiful swaths of color, complementing each other, with something always blooming in each part of the season, and I fully intended to put together a massive spreadsheet of my options so I could just select plants by the desired characteristics I needed in any given area of the garden. After several years of debating which plants to put where and not making any progress, I gave up and finally just commissioned a garden design from a professional who specializes in native plant landscapes.

I found him through the native plant nursery I frequent multiple times a year,[3] and he advertised his services as offering to create a design using plants available at that nursery. I didn’t follow his design to the letter, instead adjusting here and there with plant preferences, but even now that many of these plants are in their second year (growing to full size and blooming), I’m already thinking about where to relocate them next spring because it still doesn’t look quite right. But the trick here is making a start, which is really the hardest part (at least for me).

I’m the same way in the kitchen: I will always deviate from a recipe based on personal preferences, but I still need the recipe to serve as a reference point. To that end, starting basically from scratch in several new gardens throughout the yard has been difficult for me without someone providing a plan. (My aunt is still not retired and busier by the year – she’s also on the other side of the state – so I can’t really ask her.) For that reason, I was absolutely thrilled to discover sample pollinator garden plans earlier this year – with all of the research about plant combinations and artistic design ready to go for someone who doesn’t quite know how to get started.[4]

The Best-Laid Plans

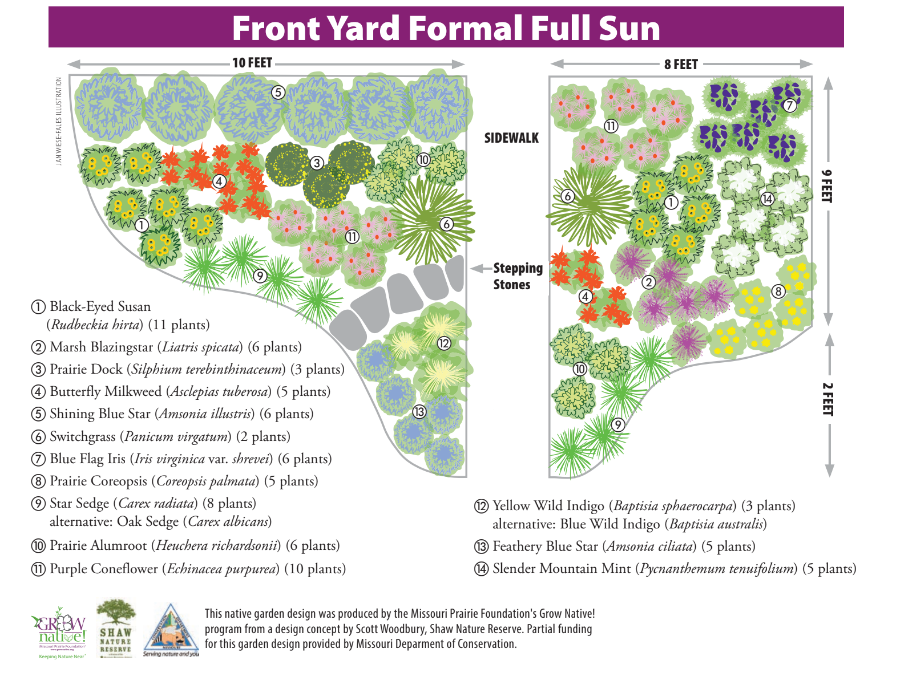

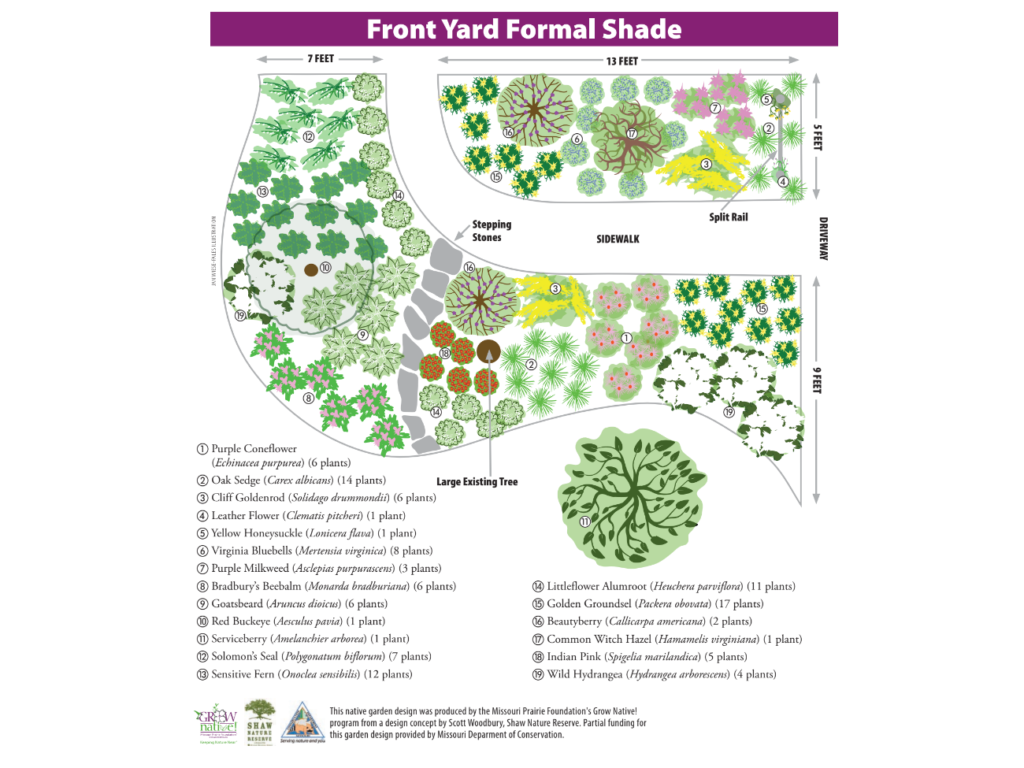

I’m not entirely sure how I stumbled across them, but I believe they were linked from the same nursery where I’ve been spending much of my disposable income for at least two years. These plans are from the Missouri Prairie Foundation and cover a variety of options, such as sun vs. shade, dry vs. wet, and desired visitors (butterflies, songbirds, hummingbirds, etc.). Given that the website is focused on Missouri, I wasn’t expecting much on the plant list that would be compatible with western Pennsylvania, but I was thrilled to be wrong when I saw several plants I recognized (and have already planted in my garden).

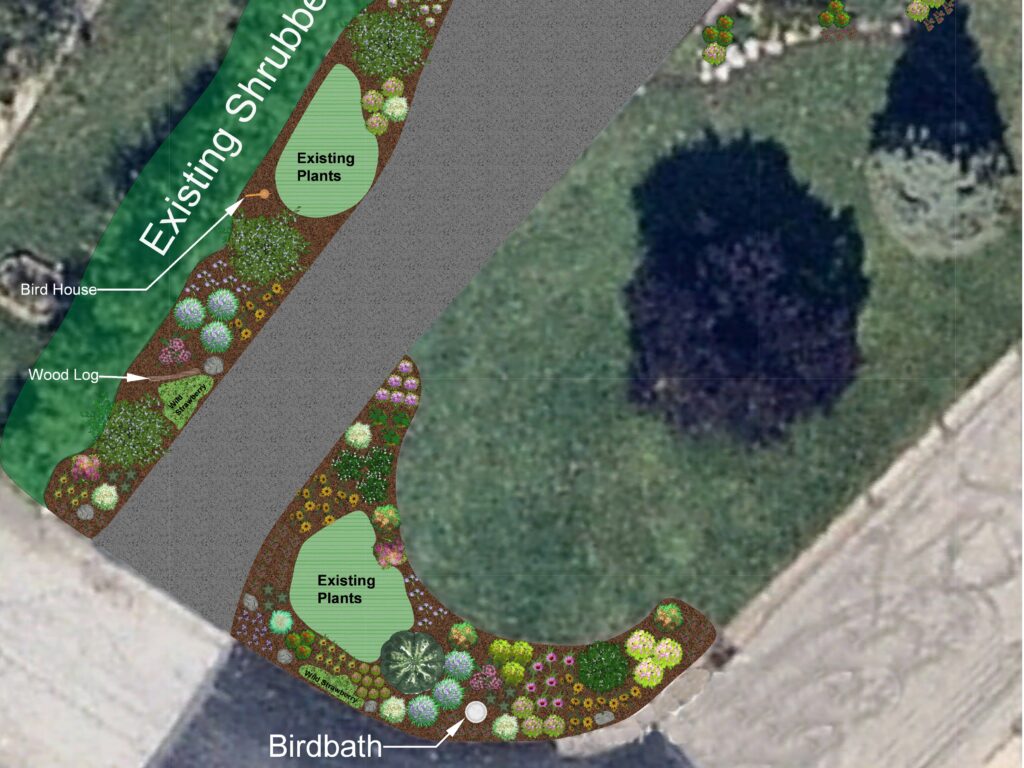

Image credit: [5]

An article linked from this page describes the values of creating an organic garden filled with native plants to support pollinators, rather than a wide span of uniform, fertilized turf grass. [6] If you are starting from scratch, the author recommends starting small (around 150 square feet or so) until you get a sense of how much maintenance you can commit to, especially in a neighborhood where turf lawns are the standard. I can attest to the fact that in the early years of starting a new garden, it is very easy for weeds (particularly stubborn grass) to fight a hard fight. We’ve received at least one nasty-gram from our borough reminding us of the local ordinances for maintaining our lawn.

For the record, my garden space, which is easily 10 times that recommended starting size listed above, was ambitious for sure, but it was also largely undertaken during the pandemic, when I really wasn’t doing much of anything else. Now that I’ve already committed to the size I have, I keep telling myself that the garden will get easier to maintain over time, which should happen as I continue to mulch (to condition the rocky, clay-heavy soil), spread corn gluten (to stop new weeds from sprouting), and let the plants I have intentionally put there fill in.

The Cost of Waiting

But getting started with a blank canvas can be daunting for some (myself included). I have friends who have told me that they want to put pollinator gardens in their yards but don’t know where to start, so they keep putting it off for another year. And I can’t really blame them. I can also attest to the fact that if you clear a space for a garden and don’t start planting it, the weeds are not going to politely wait their turn: see my thistle post from earlier this summer. [7] Having a plan when you go in can be incredibly helpful, not only so you can get moving quickly, but also so the result doesn’t look haphazard – another issue I dealt with in my first garden expansion project.

Image credit: [8]

All that said, as my aunt likes to remind me, it’s OK to move plants if you don’t like where they are. Several plants have already gone on journeys throughout my yard (and several more will next spring), which is perfectly fine as long as you’re following the instructions on how and when to move them. Another fun aspect of moving them is that sometimes if you don’t get the whole root system, you can leave a little bit behind, which is why I have black-eyed Susans growing in my yarrow – and I’m fine with that: they bloom yellow at different parts of the summer, and it looks more natural (the look I’m going for anyway).

I hope the plans on the Missouri Prairie Foundation’s “Grow Native” website give you some ideas for how to get started if you’re stuck.[9] The formal front gardens for sun and shade are specifically designed to look tidy in case you’re in a neighborhood where you’re more likely to get scrutinized for having a natural-looking yard. And as we’ve explored before on this blog, there are ways around picky, opinionated neighbors too. [10]

Since these plans are from Missouri, not all the plants listed may be native to your area. Wildflower.org has an excellent and extensive searchable list of plants that includes information about size, sun and soil preferences, bloom time, and native range. [11] Now that we’re into October, I’ll wish you happy planning instead of happy planting. But if you are looking to create or extend a garden, fall is a great time to do it. [12] As for me, I just made a big impulse purchase during a fall perennial sale, so I’ll still be at it for a while – and you can read more about that next week.

~

Are you starting a pollinator garden? I’d love to know what you’re planting! Let me know in the comments below.

Thanks for reading!

Keep reading about this year’s garden updates –>

[1] https://www.facebook.com/pharogardencentre/

[2] https://extension.psu.edu/planting-pollinator-friendly-gardens

[3] https://arcadianatives.com/

[4] https://grownative.org/learn/native-landscape-plans/

[5] https://drive.google.com/file/d/1cz5H98pjpbgGUUfDxCTmlO25kbsxW0kp/view

[6] https://drive.google.com/file/d/1cz5H98pjpbgGUUfDxCTmlO25kbsxW0kp/view

[7] https://radicalmoderate.online/thinning-a-thicket-of-thistle/

[8] https://drive.google.com/file/d/1cz5H98pjpbgGUUfDxCTmlO25kbsxW0kp/view

[9] https://grownative.org/learn/native-landscape-plans/

[10] https://radicalmoderate.online/for-the-birds/

[11] https://www.wildflower.org/plants/

[12] https://radicalmoderate.online/eco-friendly-weed-control-2020-update/

0 Comments