Part 2 – Energy and Health

After designing and running a home health and weatherization program in three Pittsburgh neighborhoods over five years, I know my way around an energy audit. After multiple certifications in building science and health, I know my way around a healthy homes assessment. I’ve worked with contractors who know their stuff and do good work – and contractors who don’t. Each hard-learned lesson from my last job came flooding back as we began soliciting proposals from roofers at Christmas.

Unfortunately, to date, I have never had a positive experience with a roofing company. The roof is not a place where you can skimp, and I have never seen a repair work the way it should, at least not for long. A problem in the roof affects the entire home, which is why all of the low-income weatherization programs I know of (run by state agencies or utility companies) disqualify or defer homes with leaky roofs. A roof leak could result in mold, and you can’t air seal a house that has mold because it exacerbates potential health problems for the people inside. Most people don’t realize how closely connected energy efficiency and health are, but they are absolutely inextricable in the built environment, which is why I am every contractor’s worst nightmare.

If I insist on a course of action, it’s because I’ve seen an example of it turning out badly before, such as an under-ventilated attic growing mold that made the residents sick. In my program, I only used weatherization contractors with Building Performance Institute (BPI) certification,[1] but even when my team checked the work, we almost always sent our contractors back to fix things they had missed.

Disclaimer: I no longer work in the weatherization industry, and I am not a licensed professional. Always talk to a professional and do your research before undertaking any home improvement projects.

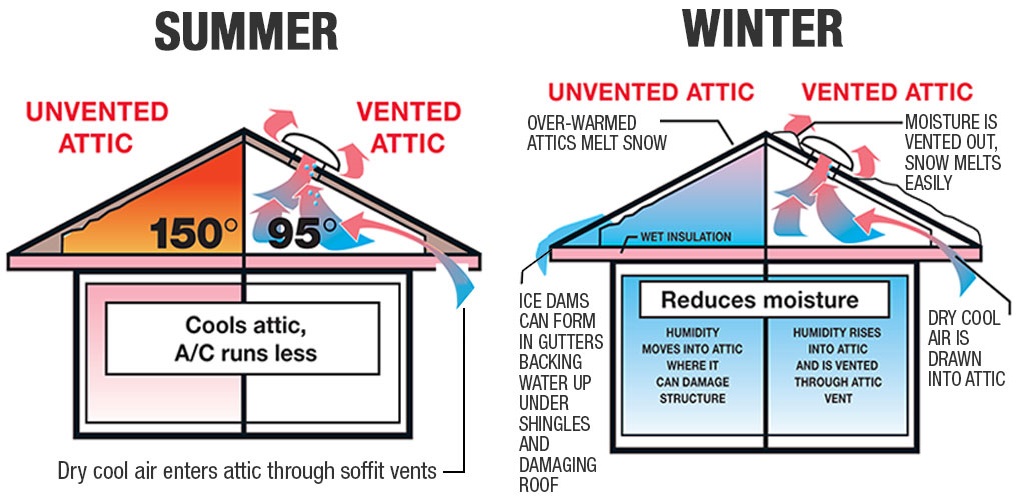

Image credit: [2]

Insulation and Air Sealing

“Weatherizing” a home involves insulating, which prevents shifts in temperature between inside and outside, and air sealing, which prevents air flow. It’s easy to think of them like wearing both a sweater and a windbreaker, which each have separate jobs but together keep you warm and dry.

As I mentioned in last week’s post,[3] we have some insulation in our attic, but not a lot, and little to no air-sealing. On top of that, our insulation was not even installed correctly – many such DIY “improvements” were completed by the previous owner, most of them unattractive at best and unhealthy at worst.

Homes have “conditioned” and “unconditioned” spaces: conditioned space is where the heated (and cooled, if you have air conditioning) air is supposed to be, while unconditioned space is more open to the elements (most garages, attics, and even some unfinished basements fall into this category). Insulation serves as a thermal barrier, keeping the conditioned space cool in the summer and warm in the winter.

There also needs to be an air seal, or “vapor barrier.” Air carries moisture in it, which condenses into water when it cools down (think of the water beads that collect on the outside of your favorite cold beverage). Because of that, the vapor barrier must always line up with the thermal barrier at the edge of the conditioned space. In our house, the attic (unconditioned) is above our living room (conditioned), and someone installed the fiberglass insulation upside-down, with the paper backing facing the attic, not the living room.

By leaving the vapor barrier on top of the insulation in the attic, you create an air gap between the conditioned space and the vapor barrier. When it’s warm in the living room and cold in the attic, moisture in that air gap can condense against that barrier, inside the insulation, which causes multiple problems. First, wet insulation becomes less effective, but also, anywhere there is moisture, there can be mold, which creates a health hazard for residents. Because some of our insulation was damaged from the leak, it made sense to take this opportunity to pull it out and properly weatherize our attic. Fortunately, I knew some guys.

Image credit: [4]

Roof Ventilation

Ironically and/or fortunately, it was our poor insulation that probably saved our roof and our health to some extent, because our attic space is under-ventilated. The only ventilation we have is in the form of very tiny gable vents (the vents you typically see at the apex of the roof on opposite sides of the house), which do not provide for much intake of outside air… only the intake of outside mice in the winter.

If we had had sufficient insulation in our attic all these years, that would have kept the attic hotter in the summer and colder in the winter. Without proper ventilation to handle these more extreme temperature shifts, condensing moisture would have stayed in the attic, creating a risk for mold, reducing the effectiveness of the insulation, and eventually reducing the integrity of the wood that makes up the roof.

These problems are still apparent but not exacerbated: warm temperatures coming up through the living room ceiling and water vapor coming in through air gaps in the attic door result in a warmer, wetter attic than we would otherwise have, and you can see water stains where moisture has condensed on roofing nails and dripped onto the attic floor. But that is about to change.

Most new roofs include a ridge vent for exhaust, which goes along the length of the roof at the top, and soffit vents for intake, which are cut into the underside of the roof along the bottom. Make sure your roofer calculates the amount of intake and exhaust vents needed for your roof so you have – at the very least – even airflow (50/50 for intake/exhaust). However, most sources now recommend creating positive air pressure in the attic by having more intake than exhaust (our contractor is doing 60/40).

Weatherization Savings

One of the perks at my last job was getting a free energy audit of my home (which also afforded the opportunity to train new employees). The energy audit involved depressurizing the house to find out where the leaks were and using an infrared camera to find out where we might be missing insulation. The report included a look at our electric and gas bills over the course of one year, and the recommendations calculated approximate annual dollars saved for each measure, based on a national database of home improvements.

The program I designed and managed was for homes in low-income communities. We were working on a budget, and every home had different needs, but we always tried to at least air seal and insulate the attic, and seal the duct work. Attic insulation is expensive but worth it for the energy savings. Sealing forced air duct work is effective and can be incredibly cheap to do, making the return on investment massive.

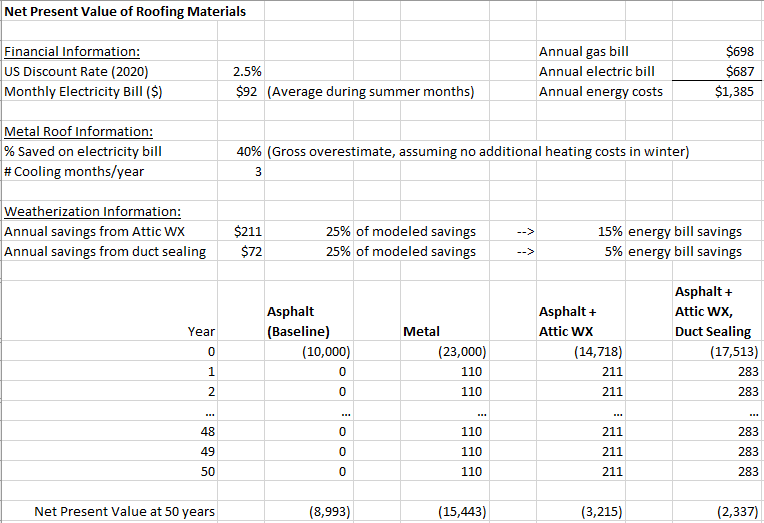

Once Christian and I were done getting roofing proposals, I called two of my former contractors to come take a look at our attic. For the purposes of this exercise, I’m going to use the more expensive estimate so I’ve got the most conservative calculations. In last week’s post I used a Net Present Value calculation to show the present-day value of all the cash flows of our 50-year roof. The baseline option is just the asphalt roof: one cash outlay at the beginning. The second option is a metal roof, with one initial cash outlay but annual energy savings after that (which, while grossly overestimated, still didn’t bring metal even with asphalt).

In this update, I have included two more options: an asphalt roof plus attic weatherization (insulation and air sealing) and an asphalt roof plus attic weatherization and extensive duct sealing. Since our energy usage is already low, I cut the estimated cost savings per measure down to 25% of what was projected in the report. That translates to a total projected drop in energy costs by about 20%, which is on par with what we achieved for the homes in my program. In any case, it appears that paying extra for the weatherization work will still be the cheapest option in the end.

Of course financial savings aren’t the only factor, and I’ve been more than willing in the past to spend extra on goods and services that promote safer, healthier options for the environment. In next week’s post, we’ll look at a lifecycle analysis of the various products.

~

Have you had weatherization work done in your home? What has your experience been like as far as comfort and savings?

Thanks for reading!

[2] http://www.elmenergygroup.com/the-importance-of-air-sealing

[3] https://radicalmoderate.online/my-cabin-doesnt-leak-when-it-doesnt-rain-part-1/

[4] https://www.menards.com/main/buying-guides/building-materials-buying-guides/roof-ventilation-buying-guide/c-19710.htm

0 Comments