Part 2 – Environmental Impacts of Production

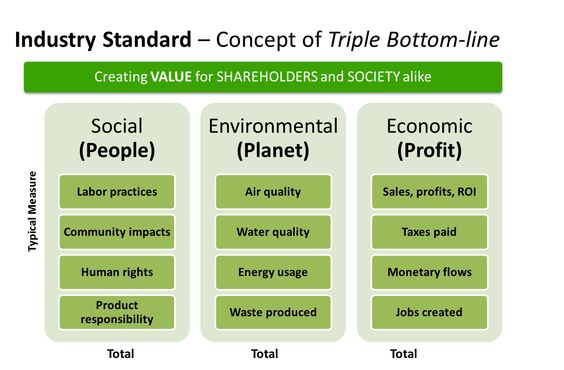

When I was getting my MBA in Sustainable Business Practices, the “Triple Bottom Line” was the newest industry catchphrase. The idea is that hard numbers associated with short-term profit cannot be the only consideration in business decisions. Examining and responding to the impacts on both people and the environment are essential from a moral standpoint as well as a long-term financial viability standpoint. The term became “Triple Bottom Line” because it incorporated People, Planet, and Profit.[1]

Last week we talked about specific health impacts associated with the production and consumption of artificial (plastic) and real Christmas trees.[2] Those health impacts (particularly those associated with plastic trees) could be experienced by people living near plastic manufacturing facilities, as well as by consumers handling PVC-based tree branches and ingesting phthalates or inhaling volatile organic compounds. Real Christmas trees could contain allergens, such as mold, or be covered in pesticides if they don’t come from an organic farm. These impacts fall largely under the “people” category (though there’s some crossover to the other categories as well). This week we’ll focus more on the “planet” category.

Objectivity in Analysis

In my research for this post, I ran across a Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) comparing artificial and real Christmas trees.[3] I’ve included information from LCA reports before on this blog, and always with the disclaimer that in this world there are “lies, damned lies, and statistics.” It is very easy to influence the findings of an LCA, depending on the scope of your analysis and the assumptions you make. The first thing that caught my eye was that this LCA was paid for by the American Christmas Tree Association (ACTA, a trade group for artificial tree manufacturers).[4]

That fact alone doesn’t automatically mean that the report is biased, but it’s something to keep in mind. The consulting group hired to perform this analysis assembled a three-person review panel to provide input on the process. The panel included the program director for Sustainability at Harvard, a professor emeritus of the Department of Horticultural Science at North Carolina State, and a senior director at the American Chemistry Council (a trade group for the US chemicals industry).[6] Looking at these names, I do wonder to what extent the client (The American Christmas Tree Association) had decision-making power in the makeup of the review panel.

The inclusion of the American Chemistry Council (ACC) raises additional questions about objectivity here. Members on the ACC website include “subsidiaries of Chevron, ExxonMobil, Shell, Total and BP.”[7] Plastics are made from oil and gas, so it follows that the oil and gas industry has a financial interest in the public perception (and consumption) of plastic in general. And plastic Christmas trees were a $2.5 Billion industry in the US in 2018.[8]

It’s also worth noting here that ACC’s former leader, Jack Gerard, left in 2008 to become head of the American Petroleum Institute (API) and was notorious for “‘aggressive’ and well-funded campaigns against Obama administration attempts to regulate the energy industry.”[9] API remains a supporter of ACC, having given over $1.2 Million between 2006 and 2018. Several of ACC’s other supporters are vocal in their opposition to oil and gas industry regulations and the existence of climate change.[10]

As always on this blog, I encourage you to draw your own conclusions, but in doing so, consider the source of each piece of information and what that source has to gain or lose from your decisions as a consumer. Certainly the professor of Sustainability would like people to be making more sustainable decisions, and the professor of Horticulture would like people to be making more ecologically friendly decisions. I simply find it curious that the third choice for the review panel was a representative from a chemical industry trade group, rather than a chemical science professor.

Impact Comparison

With that disclaimer out of the way, here is what the report had to say. The scope of the study covered the creation (either growing or manufacturing) of one Christmas tree used for one season, the transportation of raw materials to the manufacturing or cultivation site, the shipping of the tree to a retail location, and the transportation of the tree to the disposal site. There were three end-of-life scenarios for the real tree: landfilling, composting, and incineration. The artificial tree was landfilled. Both trees were 6.5 feet tall. The artificial one was made from polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polypropylene (PP), and steel, manufactured in China, and shipped to the US; the real one was grown in the southeastern US.

Manufacturing and transportation of the plastic tree were the biggest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, pollution to air and water sources, and use of non-renewable energy. The report states (buried in one of the impact descriptions) that “human health impacts and ecotoxicity were not included for this study.” They focused specifically on global warming potential, primary energy demand, acidification and eutrophication of water, smog potential, and water usage. In each case (except eutrophication potential) the plastic tree was worse than the real tree. But again, we need to consider assumptions made in the study.

When looking at the carbon footprint of growing trees, there is always a question of how to count their impact because growing trees absorb carbon dioxide, giving them a net-negative carbon footprint on their own. I attempted some calculations a few years ago on my Christmas card analysis [11] and encountered arguments that cutting down a tree (for lumber, paper, or whatever commercial product it will become) removes a tree that can be absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (meaning the tree should not be cut down for any reason), as well as arguments that the demand for lumber, paper, etc. is what put that tree in the ground at a farm in the first place.

For the purposes of this study, there was an assumption of 10.9 kg of CO2 sequestered by a 15 kg tree over an 11 year period. (For reference, the report lists the calculated global warming potential of the comparison plastic tree to be 17.9 kg CO2.) But the benefit of carbon sequestration accomplished by the real tree is offset by fuel consumption for cultivating, transporting, fertilizing, applying pesticides to, and harvesting it. Cultivation and transportation were not the biggest impacts noted in the report, however. It was, in fact, disposal – and how the consumer disposed of the tree at the end of its useful life did make a difference.

According to the report, a significant factor for the environmental impact of both types of trees is consumer behavior. Specifically, they considered the length of use for an artificial tree and method of disposal for a real tree. ACTA commissioned a similar analysis from a different consulting company in 2010,[12] and it achieved similar results (although the consulting company performing the 2018 analysis noted that approach, assumptions, and available information varied between the two studies). The 2018 analysis landed on a breakeven point of around five years. That is to say that reusing an artificial tree for five or more years will result in less of an environmental impact than purchasing a live tree for those five or more years. Conversely, if you were to purchase an artificial tree and use it for four or fewer years, it would be more environmentally friendly to have purchased real trees for those years.

But the question I was left with was what is the most environmentally friendly option for disposing of a real tree? ACTA-funded analysis covered the question but not to my satisfaction. And we will continue there next week.

~

Is your tree up yet? What choice did you make and why? I’d love to hear about it below.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/what-is-the-triple-bottom-line

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/real-vs-plastic-christmas-trees-part-1/

[3] https://8nht63gnxqz2c2hp22a6qjv6-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/ACTA_2018_LCA_Study.pdf

[4] https://www.christmastreeassociation.org/

[5] https://www.pinterest.com/pin/493214596665256685/

[6] https://www.americanchemistry.com/

[8] https://www.statista.com/statistics/209249/purchase-figures-for-real-and-fake-christmas-trees-in-the-us/

[10] https://www.desmog.com/american-chemistry-council

[11] https://radicalmoderate.online/christmas-cards-and-their-environmental-impacts/

[12] https://8nht63gnxqz2c2hp22a6qjv6-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/ACTA-Christmas-Tree-LCA-Final-Report-November-2010.pdf

0 Comments