Big Beer vs. Craft

This past fall when Christian and I took a road trip from Maine to Virginia to visit friends, one of my goals for the journey was to visit a local craft brewery every day. We almost succeeded, hitting locations in six states, but options in northern New Jersey (around my alma mater) were a little sparse. Nonetheless, I had a lot of fun trying local brews, particularly from places I’ve never heard of and can’t get at home.

The renaissance of small, independent breweries in recent years has been exciting to follow, particularly as a homebrewer (and also in light of the history that I detailed last week, with female homebrewers getting edged out of the medieval market by male-dominated, commercial production). But the battle between small, craft breweries and Big Beer rages on, and with higher stakes than one might expect.

Photo credit: Christian Korey

A Craft Beer by Any Other Name

It wasn’t until that trip, while we were sitting in Brooklyn Brewery,[3] that I realized how clearly some of these terms are defined by the industry. I had assumed that all microbreweries were inherently independent, craft breweries, but that isn’t the case. These terms indicate specific delineations about product, volume, and ownership. According to the Brewers Association,[4] a trade association for the industry, in order to be a “craft brewery” in America, you need to be:

- Small, with an annual production of 6 million barrels of beer or less (approximately 3 percent of U.S. annual sales). For reference, Yuengling and Sam Adams hover around the 3 million barrel mark. Microbreweries also have a specific definition, producing 15,000 barrels or less per year. The term “nanobrewery” is not formally defined, though that term is used to indicate production levels far smaller than microbrewery scale.

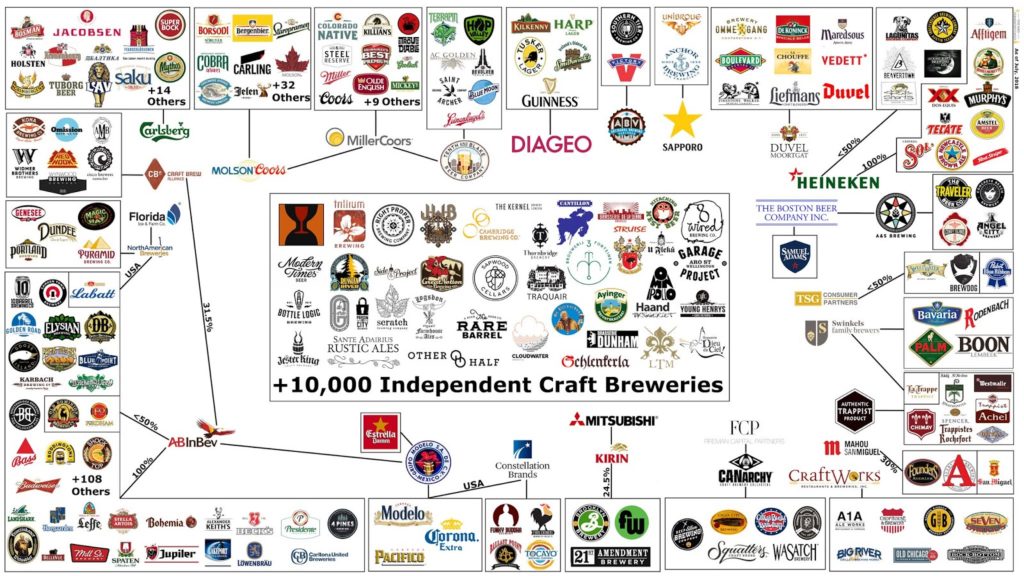

- Independent, with less than 25 percent of the craft brewery owned or controlled by an alcoholic beverage industry member that is not itself a craft brewer. For example, Elysian, Goose Island, Blue Point, and hundreds of other labels are owned and controlled by Big Beer names like Anheuser-Busch (AB InBev) and therefore not independent.

- A brewer of beer with a Brewer’s Notice from the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. That means my homebrew label does not count, as I have never registered it anywhere other than Untappd.[5]

There are certainly beer drinkers who do not pay much attention to these terms. There are plenty of beer drinkers who prefer a simple, consistent product, avoiding craft beers (even craft pilsners and lagers) whenever possible – like my father. So the question remains: does it really matter who brews your beer or who owns the brewery? It does, for a variety of reasons.

What’s the Problem?

We probably all know people who shop at farmer’s markets when they can, instead of grocery store chains; who buy from local artisans instead of from home decor chains; who eat at local mom-and-pop restaurants instead of national restaurant chains. Similarly, there are people (myself included) who try to drink beer from small, local, and/or independent breweries. There are legitimate reasons for these choices, including supporting the local economy and local jobs, fostering creativity and diversity of options, and a variety of other arguments to be made related to product quality and sustainability.

Image credit: [6]

I won’t refuse to drink beer that isn’t independent, but it’s not my preference. That being said, I also live in Pennsylvania, which ranked second in the country (after California) in 2021 for number of craft breweries and barrels of craft beer produced;[7] in Pittsburgh especially microbreweries seem to be everywhere. On top of that, I know plenty of homebrewers, and there is a nanobrewery within walking distance of our house, so we are blessed with an overabundance of choice here.

And the choices are seemingly endless… today. In the 1870s, there were over 4,000 breweries in the United States (many of which were small, locally-owned and operated breweries), but by the 1970s, there were less than 100 (many of which were large-scale producers).[8] This stark decline was, in part, a result of Prohibition followed by certain regulations after the 21st Amendment that made it easier for larger breweries to bounce back.[9]

But even before Prohibition, the widespread popularity of beer contributed to mass consolidation of production and distribution, ultimately leading to a decline of small, local, independent breweries in the late 1800s and early 1900s. (If this story sounds familiar, it should. See last week’s post about the rise of beer production in medieval cities.[10] Some research also indicates a similar pattern in ancient Egypt.[11]) And the American beer industry could be setting up for a similar cycle again, especially given the large number of corporate buyouts of independent breweries by big beer labels like AB InBev and MillerCoors.

Market Share and Control

There are heated arguments on the topic of independent craft vs. Big Beer, and – unsurprisingly – it’s a complex issue with legitimate points to be made on both sides. Some of the strongest arguments are economic. Having worked at a startup (technology, not beer), I know how difficult entrepreneurship is and that there are many considerations beyond creation of the product itself. Sometimes (especially in tech) the end goal for a startup is corporate buyout and a great return on investment.

But even when that isn’t the goal, even when founders are driven by the love of their craft (as I would say happens frequently with brewing), there are financial benefits to gaining a parent company with deep pockets – if there weren’t, the TV show “Shark Tank” wouldn’t be as popular as it is. Financial backing, production capacity, and marketing expertise, when handled by a parent company, can allow brewers to offload the “business” aspects of the work and focus on the brewing. A more stable financial footing for a brewery can ensure better pay and benefits to their employees; more streamlined production, distribution, and marketing of the product can lead to lower prices per unit for the consumer. All good things.

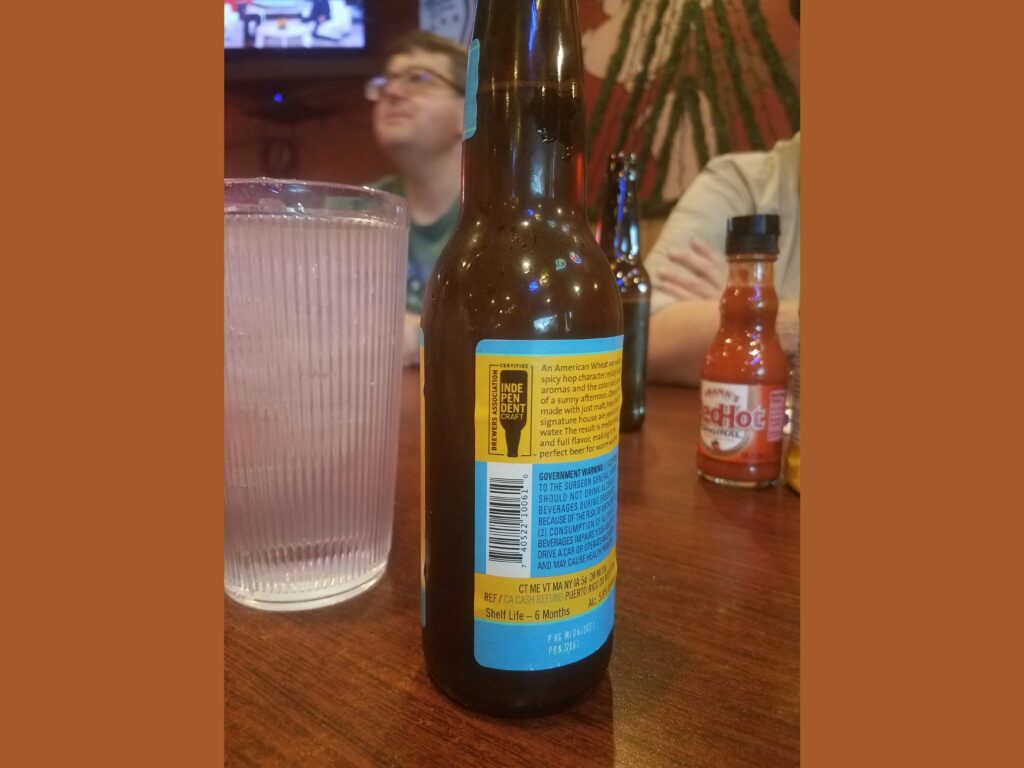

The other side of the economic argument is a little more nefarious. Big Beer’s market share is dominant, but craft’s share of the market rose 13% in 2021.[13] There are concerns that by buying popular craft breweries, Big Beer can masquerade as craft while defending its market share. Well-intentioned laws designed to support state-based alcohol production, such as Act 39 in Pennsylvania, have loopholes that can be exploited to place Big Beer subsidiaries next to local, independent, small-scale beer on shelves, where they can rely on name recognition and brand loyalty.[14] The best way to know what you’re choosing without keeping up on the extensive research required is to look for the Independent Craft Brewers Association seal, which looks like an upside-down bottle.

Ripple Effects

The tradeoff for financial security is control in these situations, and although craft buyouts often purport to leave creative control in the hands of the brewers, I would be surprised if there weren’t some restrictions in place to protect the investment. But creative control over the product isn’t the only factor to consider. Parent companies can make decisions about product distribution and marketing, employee and vendor treatment, sustainability and ethics considerations in the supply chain, and with what other organizations you do business. And those decisions can become very opaque and even concerning in larger organizations.

For example, in recent years it came to light that Japanese drinks company Kirin Holdings was (knowingly or unknowingly) providing financial support to the military in Myanmar – the military responsible for the Rohingya genocide.[15] Kirin is the parent company of Myanmar Brewery (through Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd.), and was therefore linked with payments to military units accused of war crimes.[16] Until Kirin terminated its partnership with MEHL,[17] I did not drink anything under their corporate umbrella, which was difficult in Japan (Kirin is one of the “big three” Japanese beers) and in America (their subsidiary Lion had recently purchased one of my favorite breweries, New Belgium [18]).

Of course the employees and customers of the formerly employee-owned and civic-minded New Belgium brewery had very little they could do (other than quit or boycott, respectively) when the connection with Myanmar’s military came to light. That’s not to say smaller breweries are immune to scandal – they aren’t – but there can be a more nimble, meaningful response in situations when there is more transparency and less organizational inertia. And that’s where we’ll pick up next week: with the handling of more systemic equity issues in the industry at large.

Until then, what are you drinking and why?

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://www.footbridgebrewery.com/

[2] https://www.atlanticbrewing.com/

[3] https://brooklynbrewery.com/

[4] https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/craft-brewer-definition/

[5] https://untappd.com/PoorKittyBrewingCompany

[6] https://vinepair.com/booze-news/craft-brewery-ownership-chart/

[7] https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/state-craft-beer-stats/?state=PA

[8] https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/

[9] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/what-caused-the-death-of-american-brewing-21155872/

[10] https://radicalmoderate.online/equity-in-brewing-part-1/

[11] https://beerandbrewing.com/how-women-brewsters-saved-the-world/

[13] https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rohingya_genocide

0 Comments