A (Brief) History

For Valentine’s Day 2014, I bought a beer brewing kit for my then-boyfriend as something fun we could do together. After it went untouched in my apartment for two months, I decided that it would instead be something fun I could do by myself – which I did, while he watched TV in the living room. And starting with that first little 10-bottle oatmeal stout kit from Brooklyn Brew Shop,[1] which I made in my tiny apartment kitchen, I ventured down a path (or rabbit hole, or slippery slope) into the world of brewing…

It was (and is) world full of incredible things to learn about history, and anthropology, and chemistry, and microbiology, and economics; a world where art and science blend in delicious ways, and where I could learn those things by doing them myself; a world that expanded for me as I bonded with my future husband over the one good craft beer on draft at a bar, as I became great friends with a clerk at my local homebrew shop, and as I took the reins of my local brewers guild (as its first – but not last! – female guild head).

Brewing, for me, has always been about far more than just drinking. It is a creative outlet for someone who loves to be in the kitchen, a vast and complex subject with a lifetime of ingredients, techniques, processes, etc. to learn, and a way to connect with others. The more I studied the history of this once essential industry that is dominated today by men (many of them white, many of whom love to mansplain), the more I was thrilled to discover that by being a female brewer – particularly a female homebrewer – I was getting back to the roots of a practice that was originally the realm of women. And as a medievalist, I completely embraced that piece of history.

A Woman’s Place is in the Brewhouse

Women have been associated with brewing – depicted in artwork and legends – for the vast majority of alcohol’s role in civilization, from the sacred to the mundane, and from as early as 7000 BC to modern day in some parts of the world. And while my familiarity with the history of brewing is most closely focused on the European Middle Ages (England specifically), there is evidence of women being the primary or exclusive brewers of alcohol in cultures across the world, and more than one instance of women getting pushed out of the practice by men and male-owned, centralized, production breweries during periods of industrialization.[2]

At the height of my involvement and productivity in this hobby, I was making four or five meads and two or three beers each year, with each batch being about five gallons. That comes to an average of 35 gallons of alcohol coming out of my kitchen each year. While it’s certainly more than Christian and I can consume on our own in the time of clean water, restaurants, and beer distributors, it represents a tiny fraction of what I might have regularly produced if we lived in the Middle Ages.

In my time period and location of interest as a medievalist, brewing was considered women’s work as part of taking care of the household and providing sustenance for its residents. According to a book I have leaned on heavily in my research and teaching over the past few years, Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600, a household of five might consume almost nine gallons of ale a week.[3] At that modest ¼ gallon of ale consumption per day (other sources say as much as one gallon per person per day [4]), that would put my minimum necessary output for our household of two at more than 180 gallons per year, or five times what I was making as a hobbyist.

From my time researching and brewing historic recipes, I know that in England before about 1400 AD the drink called “ale” was not what we think of as “ale” today. Medieval ales were malt-based but did not include hops. The hopped, malt-based beverage that has persisted to today was known at the time as “beer” – distinct from “ale” – and was more common on the continent, particularly in the Netherlands. Instead of hops, women in the countryside during this time used a variety of herbs to flavor their ales, mask any sour flavor, and even give it some medicinal properties. Ales were frequently flavored with heather, ground ivy (a.k.a. Creeping Charlie), and “various other bitter and aromatic herbs, such as Marjoram, Buckbean, Wormwood, Yarrow, Woodsage, or Germander and Broom.”[5]

As any modern IPA fan will tell you (whether you want them to or not), hops act as a preservative. In the absence of hops, these medieval ales would spoil, turning sour quickly, particularly in hot weather. (I can confirm from my own experience.) Because of that feature, ales were brewed in a more decentralized fashion and were consumed quickly. Consequently, small co-ops could form in towns, in which women rotated brewing responsibilities, ensuring a supply for their own families and selling the excess ale while it was still fresh. There are, to my knowledge, no existing documents showing formal schedule rotations, but it is believed that families could supplement their own brewing with the purchase of ale from other households or small commercial brewers.[6]

“The City calls for Beer”

Meanwhile, it was harder to ensure sufficient supply of ale in city centers, where demand could fluctuate. Either you brewed too much, and your stock spoiled, or you didn’t brew enough, and you lost potential revenue. Moving into the 1400s, England saw a decoupling of brewing and selling, much like what had been happening on the continent, which was enabled by the introduction of hops for the creation of “beer.” Since beer had a longer shelf life than ale, larger, more centralized, brewing operations became possible, with distribution to establishments that served thirsty patrons. Sometimes joint ventures arose with bakers and butchers so these establishments could sell food too – and the rest is history.[7]

Unsurprisingly, these commercial ventures were headed by men, who had far more social latitude to go into business on their own. Given the realities of economics and logistics in the city, it’s possible that the dominance of beer over ale as a function of industrialization was inevitable. However, ale – and the women who brewed it – also had to contend with smear campaigns that called into question the cleanliness of the homes where ale was brewed, (implying that commercial facilities were safer), the ingredients that were used (implying that lack of regulation was dangerous), and the health or even the piety of the brewers (implying a connection with witchcraft).

While the true level of connection with accusations of witchcraft is debated by various academics,[9],[10] there is a striking similarity between items and images traditionally associated with female homebrewers (large kettles for brewing, brooms for cleaning, cats for catching mice, etc.) and iconography associated with witches.[11] No matter how much of a role this possible propaganda played in discouraging the purchase of homebrewed ales or the involvement of women in the industry altogether, unhopped medieval ales lost popularity to the point of extinction by around 1700 in England, at which point hopped beers became the standard, and the term “ale” referred to a type of beer fermented at or around room temperature (which it still does today).[12]

Fast-forwarding to modern day (or close enough), we see advertisements from the mid-twentieth century painting beer as a drink for men, with women (if included at all) as the ones serving or promoting it, but not as the target audience.[13] Commercial brewing continues to be dominated by men, particularly with respect to Big Beer. With the much more recent renaissance of small, independent, craft breweries, we have seen increased representation by women and minorities in what has been a largely male and white industry, but there is a lot to consider and a long way to go toward anything resembling equity. We will get into a lot of that in the coming weeks.

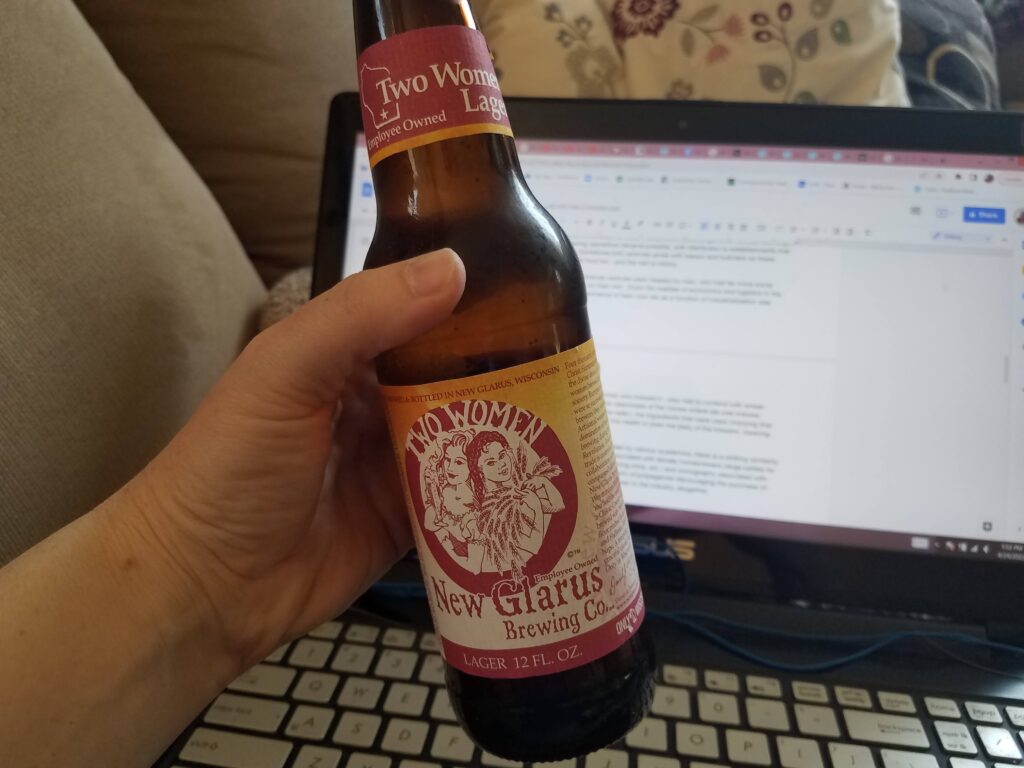

Until then, cheers! What are you drinking and why?

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://brooklynbrewshop.com/collections/beer-making-kits/products/oatmeal-stout-beer-making-kit

[2] https://beerandbrewing.com/how-women-brewsters-saved-the-world/

[3] https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/490054.Ale_Beer_and_Brewsters_in_England

[4] https://www.alcoholproblemsandsolutions.org/alcohol-in-the-middle-ages/

[5] https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/157268.Sacred_and_Herbal_Healing_Beers

[6] https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/490054.Ale_Beer_and_Brewsters_in_England

[7] https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/490054.Ale_Beer_and_Brewsters_in_England

[8] https://newglarusbrewing.com/beers/ourbeers/beer/two-women

[11] https://braciatrix.com/2017/08/07/witchcraft-alewives-and-economics/

[12] https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/490054.Ale_Beer_and_Brewsters_in_England

[13] https://beerandbrewing.com/how-women-brewsters-saved-the-world/

0 Comments