Part 2 – Animal Welfare

The most obvious and oft-quoted reason for going vegan is animal welfare – and we do eat a lot of animals. Because of our consumption habits, it is commonly perceived that a vegan diet will save 95 animals per year, hence the name of this advocacy book, Ninety-Five.[1] That estimate is low, according to The Vegetarian Calculator,[2] which says that I, going on 20 years of vegetarianism this year, have saved over 4000 animals in that time (200 per year) – a number that would have been over 7300 according to the Vegan Calculator [3] if I had been completely vegan (365 per year, which sounds extreme, even for my carnivore husband).

Of course these numbers are pure speculation and based on averages, but what is known is that Americans are eating, on average, 225 pounds of meat every year.[4] That statistic, when measured in grams per person per day, puts us in the top three meat-consuming countries in the world, after Hong Kong and Australia.[5] And one need not go far online to hear about the terrible conditions in which many animals bred for food must endure.

When looking at animal consumption from a supply and demand perspective, several leading animal rights advocates point out that reducing your intake of animal products won’t save an animal from a farm (think of farm animals being released from a slaughterhouse to go live the rest of their lives in a sanctuary), but will rather reduce demand for that product so that future animals providing it won’t be bred in the first place.[6]

More Local, Less Commercial

Veganism for the animals’ sake is actually lower down on my priority list because I already try to be as mindful as possible when buying food, particularly anything that uses animal products. I typically buy milk and eggs from small, local farms, which tend to be more transparent about their operations. I eat local honey, sometimes very local (from my neighbor’s hives). I don’t often buy cheese, but when I do, I try to support small, local farms there, too. (Christian, on the other hand, buys plenty of cheese, and if it’s in the house, I’m going to eat it. So the vast majority of the blame goes to him on that front.)

In last week’s post I mentioned that I tend to avoid vegan substitutes for common foods, and there are a few reasons for that. First, when I did the Whole30 challenge [8] about five years ago, one of the strict guidelines was not to try to make foods you love with the remaining ingredients you’re allowed to eat. The idea was to change your eating habits and focus on dishes that let the “allowed” ingredients shine, rather than choking down sad almond flour pancakes. Part of my inclination to make tasty dishes from scratch, rather than leaning on pre-packaged vegan meat/dairy substitutes, comes from this intense approach.

I also think twice before buying certain branded, packaged vegan alternatives because the added processing, packaging, and transport associated with them contributes to added carbon footprint, as I discovered in my Community Supported Agriculture series last year. It’s not a huge amount, but it’s a much larger percentage of the total footprint for plant-based foods, and I want to cut back wherever possible. But finally, the larger the operation, the more chances there are for economies of scale that can have negative, if unintended, impacts on animal welfare. And if “animal welfare” is your reason for veganism, it isn’t just the farm and dairy animals we need to be worried about.

Unseen Animal Impacts

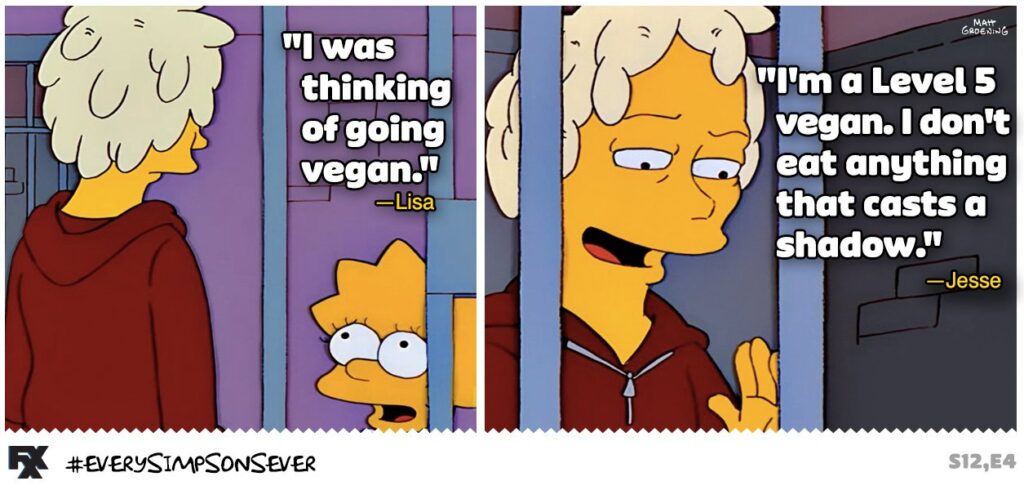

Vegans tend to draw the line in different places as to what they will and will not eat. Most vegans I know do not eat honey because commercial honey farms exploit bees. (Some vegans are more flexible – for example, I have a friend who will drink the mead I brew because she knows I’m thoughtful about where I source my honey, but she won’t eat honey herself.) Some vegans who don’t eat honey will use agave syrup instead to spare the bees, but a run on agave (mostly for tequila, but for syrup as well) is proving harmful to endangered bat populations who need the agave to live.[9],[10] While honey is a common product to avoid because of the bees, I don’t know any vegans who avoid tequila because of the bats.

Similarly, almonds serve as the basis for a very popular (and delicious) vegan milk alternative and a tasty snack rich in vitamins and minerals. When I was on Whole30, almonds, almond butter, and almond milk all made up a significant portion of my daily food intake. Almonds seem like a godsend for people who don’t want to contribute to the exploitation of dairy cows. However, for anyone who doesn’t eat honey because of bee exploitation, almonds should be off the table as well. Most commercial beekeepers’ revenue comes not from honey, but from shipping out their hives to pollinate crops, most notably California’s almond crops. The process is incredibly stressful for the bees, and, it is believed, likely contributing to massive hive collapse through factors like monoculture and glyphosate exposure, both of which can weaken bee immune systems.[12],[13]

Additionally, cultivated crops are notoriously hard on the land and the animals that try to live there. Animals are regularly killed by machinery as land is cleared or tilled, or as crops are harvested. Others are intentionally killed with pesticides in order to protect the crops. Some of the more inflated numbers on this subject [14] have been debunked,[15] but there is no denying that any commercial soybean harvest, for example, is likely not entirely vegetarian, thanks to many of our modern, mechanized farming practices.[16]

My intention here is not to lecture anyone for drinking almond milk – far from it. My intention is simply to point out that the definition of “vegan” can get more blurry the closer you look. There are virtually no options that remove risk of animal exploitation or death unless you plan to grow all of your own food, and even then, the impacts from your decisions related to fertilizer, pesticides, and and so on may not be entirely clear. At least by growing your own food – or starting with whole foods when you cook – you’ll have a better sense of what you’re putting in your body. And the health aspect is where we’ll pick up next time.

But until then, I’ll leave you with a vegan recipe that graced my table this week.

Recipe: “Not Terrible Lentil Soup”

This recipe is adapted from one of my favorite cookbooks: formerly known as “Thug Kitchen,” [17] now known as “Bad Manners.”[18] I tried it out after getting some fresh kale at a local farmer’s market, while also adjusting the recipe based on what was available in my kitchen. It was by far the best lentil soup I’ve ever had.

Ingredients:

- 2 tsp olive oil

- “2” cloves garlic (Haha!)

- ½ onion

- 1 carrot, diced (I used a lot more because they were on their way out.)

- 1 tsp paprika

- 1 tsp turmeric

- ½ tsp cumin

- ½ tsp ginger

- ¼ tsp salt

- 1 Tbs tomato paste (I didn’t have this and tossed in some adobo peppers instead. Good move.)

- ½ c red lentils (I had green.)

- ¼ c quinoa (I was out, so I doubled the lentils.)

- 5 c vegetable broth

- 3 c chopped spinach or kale

- 1 Tbs lemon juice

Heat the oil and saute the onion, carrot, and garlic until soft (about 4 minutes). Stir in paprika, turmeric, cumin, ginger, and salt. Add tomato paste, lentils, quinoa (or whatever else you’re using here), and stir until mixed. Pour in veggie broth and simmer until lentils/quinoa are tender (about 25 minutes).

Stir in greens and lemon juice and simmer until greens wilt (about 3 minutes). Season to taste.

~

Let me know if you try the soup. In the meantime, what are your favorite vegan recipes? I’d love to hear about them below.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/7293042-ninety-five

[2] https://vegetariancalculator.com/

[3] https://vegancalculator.com/

[4] https://aei.ag/2021/04/05/u-s-meat-consumption-trends-beef-pork-poultry-pandemic/

[5] https://www.atlasandboots.com/travel-blog/countries-that-eat-the-most-meat/

[6] https://www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2015/03/12/392479865/does-being-vegan-really-help-animals

[7] https://www.veestro.com/blogs/food-for-thought/what-difference-can-one-person-make-by-going-vegan

[9] https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/10/29/560292442/bats-and-tequila-a-once-boo-tiful-relationship-cursed-by-growing-demands

[10] https://acti-veg.com/agave-is-worse-than-honey/

[11] https://twitter.com/everysimpsons/status/950895082739257344

[12] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jan/07/honeybees-deaths-almonds-hives-aoe

[13] https://radicalmoderate.online/roundup-and-glyphosate-part-3/

[14] https://theconversation.com/ordering-the-vegetarian-meal-theres-more-animal-blood-on-your-hands-4659

[15] https://theconversation.com/vegetarians-cause-environmental-damage-but-meat-eaters-arent-off-the-hook-6090

[16] https://www.veganaustralia.org.au/animals_harmed_in_plant_food_production

[17] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/30820811-thug-kitchen-101

[18] https://www.badmanners.com/change

0 Comments