Part 2 – Cyclical Harm

Last week we talked about the dangerous practice of using the term “recycling” related to steps in the plastics lifecycle that are not. Specifically, over 90% of plastic products (many of them single-use) do not get recycled, but recycling as a concept was pushed heavily by the plastics industry to help assuage consumer guilt (and drive more consumption), beginning in the 1990s.[1] The idea was that if a product was recyclable, we wouldn’t have to worry about how much we bought, or used, or threw into our recycling bins.

If you did not read last week’s post or the healthy disclaimer attached, I encourage you to do so now.[2]

As I mentioned in Part 1, even I have become more lax with regard to my single-use plastic vigilance since a local private recycling company began accepting plastics to create a landscaping product backed by Dow Chemical (keep that seemingly random connection in mind for later). This strategy of encouraging consumption by offering a “solution” to plastic waste means not only creating new products by melting different types of single-use plastics together (downcycling, not recycling), but also by converting plastics back into fossil fuels through a method called “chemical recycling.”

Small Scale

This concept first appeared on my radar a few years ago when I saw an ad (most likely in my Facebook feed) describing a small, portable machine that could turn plastic waste back into oil. Noble in concept, the idea was hatched to address the dual problems that many developing countries are inundated with plastic waste and also have limited energy infrastructure. Using this machine, residents could 1) create a use for the massive amounts of plastic waste they live with on a daily basis, and 2) help support a diversified, decentralized mix of energy sources. And as a bonus, it would support local economies by monetizing a novel solution. The concept – in theory – sounded inspired; the concept – in practice – sounded too good to be true.

The machine, named Chrysalis, was hailed by the plastics industry as a brilliant solution to the global plastic waste problem.[3] Chrysalis is a project under the aegis of Earthwake, a company dedicated “to be a laboratory and an incubator of low-tech innovations, accessible to all, dedicated to waste repurposing around the world.”[4] The benefits of such a process are clear: there are currently an estimated 6.3 Billion tons of plastic waste across the world, and nowhere to go with it. Initiatives supporting small-scale, “micro-entrepreneurs” as they are described in the plastics industry article linked above, are incredibly meaningful in bolstering local economies and – in this case – addressing an ongoing and growing problem.

There are two reasons I feel the need to pause and ask more about this process and its implications. The first is that, while we absolutely need to do something about our plastic waste problem, we – again – need to be careful about treating what should be a last course of action as a “get out of jail free” card. The second reason is that – very often – when we talk about decisions and actions that impact the environment, our focus is on waste or temperatures; we less often pay attention to more subtle factors, such as how various types of pollution impact public health. And to illustrate both of those points, we need look no further than our own backyard, in the United States.

Large Scale

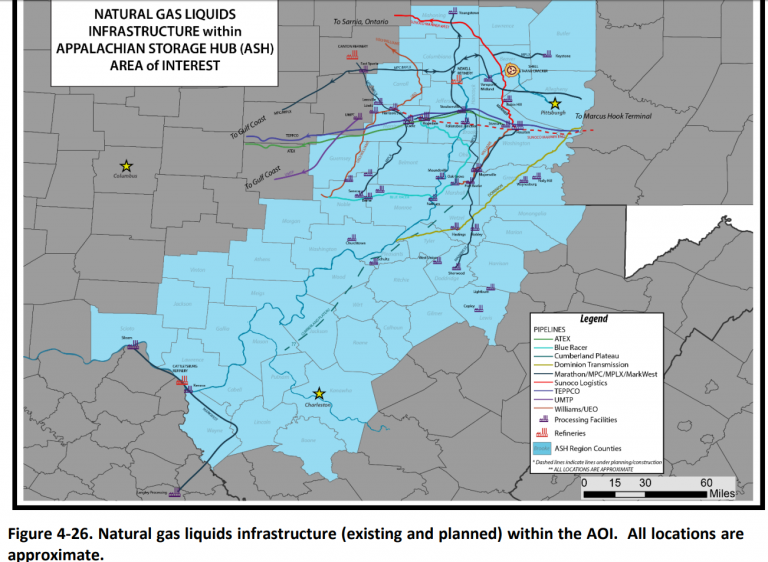

I’ve spent time before on this blog talking about Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, an 85-mile “sacrifice zone” that is home to 150 petrochemical facilities and refineries. The environmental justice issues associated with this area have been called out by a range of sources, from the United Nations[5] to John Oliver.[6] There are still unknowns about exposures and health impacts resulting from the “chemical recycling” process, but we know there are many health concerns associated with the petrochemical industry writ large – as we currently see in Louisiana, and can expect to see in coming years thanks to a planned Appalachian petrochemical hub.[7]

Image credit: [8]

As described with Chrysalis, much “chemical recycling” is not recycling at all, but instead plastic-to-fuel conversion. The insidious thing about using the term “recycling” is that it serves as greenwashing for multiple industries we need to be moving away from quickly. There are indications that transforming plastic into fuel “poses the same environmental health concerns as waste incineration.”[9] And then, we take that fuel and burn it for heat, or power, or transportation, further contributing to climate change in the process.

Yes, plastic waste is a problem to address, but no matter how we address it, we should not be making more plastics and thinking there is any kind of solution to counteract the anticipated doubling of global plastic waste over the next 20 years.[10] Yes, climate change driven by a fossil fuel-based economy is a problem to address, but no matter how we address it, we should not be thinking that turning plastics into burnable fuel doesn’t count toward our global carbon budget because it was “already” plastic.

The thing to consider is that whether you’re talking about the oil and gas industry or the plastics industry, no one is building a “chemical recycling” facility out of a desire to save the planet. There are sizeable profits to be realized on this avenue, not to mention continued support for processes that should be ramping down, not up. Building such facilities locks us into a plastics-based economy for decades to come – and that means more plastics production and more extraction of fossil fuels to create plastic.

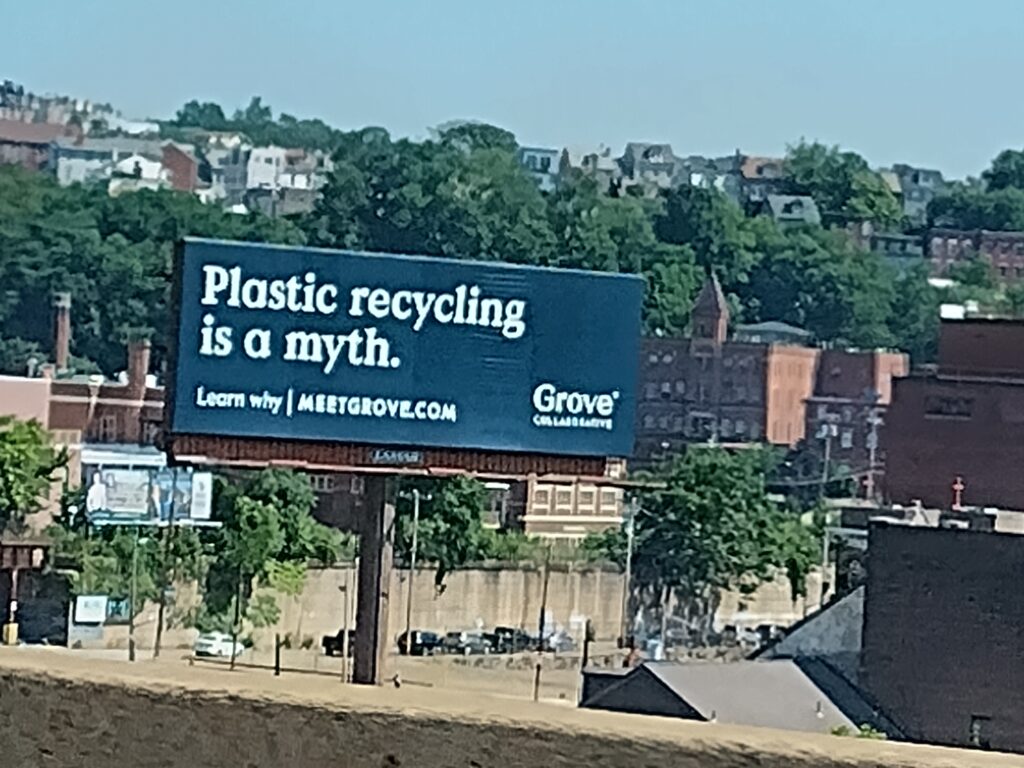

Photo credit: Christian Korey

The first step toward changing this trajectory involves changing our perceptions around plastics. The ideas that they are necessary, that they are recoverable, and that they are safe for our health are myths backed by a multi-billion dollar industry (plastics),[11] which is backed by a multi-trillion dollar industry (oil and gas).[12] Next time we’ll take a look at the work being done to shift this narrative.

Thanks for reading!

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-2022-part-1/

[3] https://plastics-themag.com/Chrysalis-the-machine-that-converts-plastic-waste-into-fuel

[4] https://www.earthwake.fr/en/transform/

[5] https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/03/1086172

[7] https://ohvec.org/appalachian-storage-hub-petrochemical-complex/

[8] https://ohvec.org/appalachian-storage-hub-petrochemical-complex/

[11] https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/global-plastics-market

0 Comments