Part 2 – The Accident

Japan is made up of four large islands. The main one is called Honshu (literally Base State), which is where most major tourist attractions (such as Tokyo, Kyoto, and Mt. Fuji) are located. If you think of Honshu as being shaped roughly like a “J,” it can be divided into the north-south part and the east-west part, with Tokyo in the middle. The main tourist track lies in the east-west portion of Honshu, with Tokyo in the east, Kyoto in the middle, and Hiroshima in the west. The land north of Tokyo was traditionally considered to be uncultured, back-woods country, if not the frontier.

Japan is broken up into 47 prefectures (similar to states). Fukushima is the southernmost prefecture in the region called Tohoku (literally East-North). It is the third-largest prefecture by area in the country, after Hokkaido (the northern island) and Iwate (another prefecture in Tohoku); it sits on the Pacific coast and stretches west into the mountains, taking about three hours to drive end-to-end on a toll road; it is shaped roughly like Australia (as Australian expats are wont to point out).

As a less-affluent area, Fukushima was host to two nuclear power plants that did not generate electricity for Tohoku, but rather for Tokyo. In fact, our tour guide from Japan Wonder Travel[1] told us that one third of Tokyo’s electricity comes from Tohoku-based generation. Land is cheaper and less densely populated in the countryside, so Tokyo Electric Power Company, a.k.a. TEPCO, built two of their nuclear power plants in Fukushima, which sits in the Tohoku Power territory. These plants are known as Fukushima Daiichi (“Number One”) and Fukushima Daini (“Number Two”).

The Fukushima Daiichi site was host to six reactors (four of which will factor into this story) and is located about 100 kilometers south along the coast from Sendai, the largest city in Tohoku (over 1 million people in 2010). The Daini site houses four reactors and sits about 12 kilometers south of Daiichi. An additional 40 kilometers south from Daini is Iwaki, Fukushima prefecture’s largest city (about 340,000 people in 2010).[2],[3] Given each site’s distance from the epicenter of the 2011 earthquake, the resulting tsunami hit Daiichi first… and harder.

Image credit: Japan Wonder Travel

The Earthquake

The magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck approximately 130 kilometers (80 miles) east of Sendai at 2:46 pm on Friday, March 11. Both Daiichi and Daini were unharmed by the earthquake, having been built to specifications based on the 1960 Chile quake, which is to-date the largest instrumentally-measured earthquake on record (magnitude 9.5) and caused tsunami worldwide, including in Fukushima.[4] Sustaining no damage from the seismic activity, all operating reactors (three at Daiichi and four at Daini) went into automatic shutdown as soon as the earthquake hit.

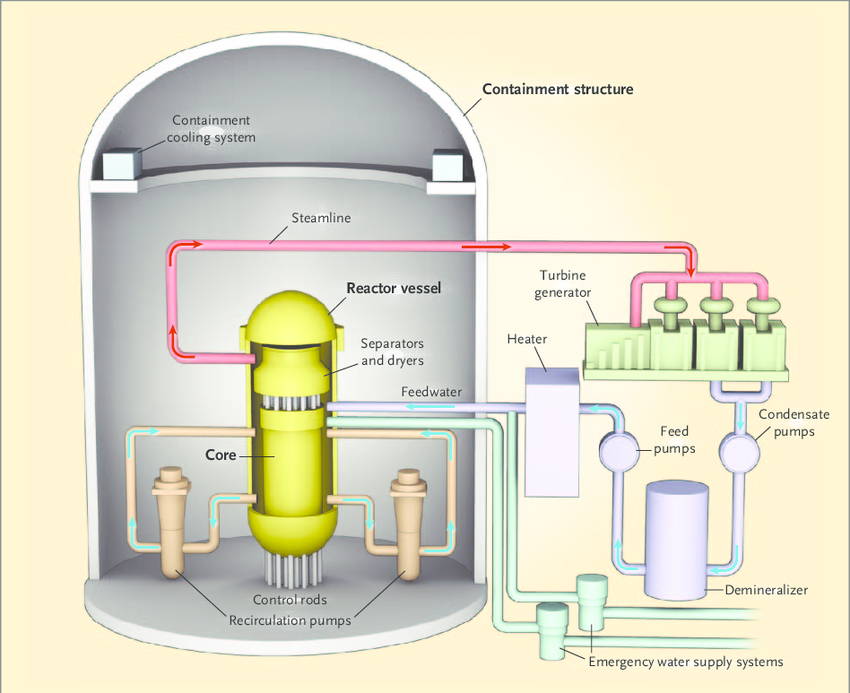

Shutting down a nuclear reactor involves inserting control rods among the fuel rods in the reactor chamber to slow the chain reaction of Uranium-235 fission. A Uranium-235 atom breaking apart into smaller elements releases 2.5 neutrons on average; only 1 free neutron is needed from each fission to sustain a steady reaction, which is why control rods are necessary during normal operation, not just in shutdown. Control rods are made from materials such as cadmium, hafnium, and boron, elements that can absorb free neutrons without undergoing fission themselves.[5] In an emergency shutdown, or “SCRAM,” control rods are quickly inserted and can stop any new fission within seconds.

While fission stops almost instantly in the event of a SCRAM, the radioactive elements continue to decay, creating additional heat. Reducing heat in spent fuel is an incredibly slow process. After a SCRAM, it will still take days (at least) of active cooling to bring the reactor to “cold shutdown,” which only means the water is below boiling temperature. The fuel itself requires continuous cooling for years after shutdown before it is cool enough for dry storage.

The automatic SCRAM of the Daiichi and Daini reactors proceeded as designed, but the earthquake damaged the off-site power supplies at both locations, cutting off necessary power for cooling and monitoring equipment. In the absence of external power sources, emergency diesel generators located below the turbine buildings kicked on.

Image credit: [6]

The Tsunami

At 3:42pm, the tsunami reached the Fukushima coast at Daiichi. The site was built at 10m (almost 33ft) above sea level and was designed to withstand a 3.1m (10ft) tsunami. The wave was 15m (almost 50ft) by the time it reached Daiichi. The wave submerged the seawater pumps and damaged the diesel generators, electrical switchgear, and batteries, which were all located in the basements of the turbine buildings. The battery backup for cooling equipment in Reactor 3 survived and would remain operational until its power ran out 30 hours later.

The earthquake and tsunami together took out multiple backup systems at Daiichi that should have withstood one, the other, or smaller instances of both, resulting in a station-wide blackout with no ability to cool the fuel or even monitor pressure in the reactor vessels. Access to the site by emergency and support vehicles was severely limited by earthquake and tsunami damage, so there was no way to reconnect the site to external power sources.

Meanwhile, to the south, the tsunami’s height had decreased to 9m by the time it reached the shore at Daini, which was built 13m above sea level. The site still lost power from all but one remote source after the earthquake and suffered some damage to generators from the wave, but it managed to avoid blackout status. There were challenges in providing enough power to cool the reactors over the coming days, but all four achieved cold shutdown (below 100 C) by Tuesday, March 16.[7]

The Reactors

Once it became clear that there was no way to cool the reactors at Daiichi, a nuclear emergency was declared at 7:30pm on March 11, and an evacuation order was issued for people within 2km of the plant while crews worked to restore power and cooling. The evacuation order was increased to 10km and then 20km the following day, resulting in the total evacuation of 160,000 residents.

While the battery backup remained operational on the cooling system in Reactor 3, pressure began to build up in Reactors 1 and 2. The lack of operational cooling systems allowed the water inside each reactor vessel to boil, exposing the fuel rods to air, which allowed the fuel to heat up faster. Without water, the heat inside reached an estimated 2800 C (over 5000 F), and the fuel began to melt. Crews attempted to inject fresh water directly into the reactors as an emergency measure. When the fresh water ran out, they continued with sea water.

In an attempt to reduce pressure on Reactor 1, the steam (containing hydrogen, oxygen, and radioactive material) was released from the reactor vessel, but instead of venting out the stack, it leaked into top of the containment building, where pressure built up. Over the next several days, pressure from water vapor and excess hydrogen resulted in explosions of containment buildings for Reactors 1 (March 12), 3 (March 14), and 4 (March 15), with a leak developing in Reactor 2, which is believed to be the major source of radiation leakage on site. Spent fuel, which was stored above the reactors, became exposed to the atmosphere after the explosions.

In the following weeks, sea water was used on the exposed fuel to help cool it down, being dumped by helicopter and sprayed by water cannons. Offsite power was restored to Reactors 1 & 2 by March 21, and to 3 & 4 by March 22. Cooling efforts continued by spraying sea water onto the spent fuel, with fresh water becoming available again at the end of March.

Aftershocks from the March 11 quake resulted near and in Fukushima prefecture on April 7 (7.1 magnitude), April 11 (7.1), and April 12 (6.3), but caused no further damage to the plants. Cooling efforts continued throughout the year, and the Japanese government announced that a stable cold shutdown for Reactors 1-3 was achieved on December 16.[8]

According to the World Nuclear Association’s very detailed summary of events, three TEPCO employees were killed directly by the earthquake and tsunami while at the Daiichi and Daini sites. There were no direct fatalities from the nuclear accident.

Next week we will look at the aftermath of the disaster and present state of Fukushima’s exclusion zone.

Thank you for reading.

[1] https://japanwondertravel.com/

[2] Distances: https://www.google.com/maps

[3] Population numbers: https://www.wikipedia.org/

[4] https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/hazard/data/publications/1960_0522.pdf

[5] https://energyeducation.ca/encyclopedia/Control_rod

[6] https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Key-Components-of-a-Nuclear-Power-Plant-In-a-boiling-water-reactor-the-type-in-use-at_fig1_51064250

[7] https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/safety-and-security/safety-of-plants/fukushima-daiichi-accident.aspx

[8] https://www.oecd-nea.org/news/2011/NEWS-04.html

2 Comments

Passport Overused · March 15, 2020 at 12:41 pm

Great post 😁

Alison · March 29, 2020 at 10:53 am

Thanks!