May is the best month of the year, and I will brook no dissent on that subject. I am sad that it is coming to an end, but I have a way to extend it a little longer and make me think of the first warm days of the year when the world starts to come back to life.

A month or so ago, some of my friends from college posted on Facebook about the violet syrup they were making – an annual tradition for one couple and a newly adopted one for another. Around the same time, a friend from Pittsburgh was telling me about the honeysuckle syrup she made last year and how she would be making more again.

Given the renewed energy that comes with spring and watching my garden grow, I was excited to give both of these recipes a shot myself. By the time this post goes live, most violets around here will be gone, but there may yet be some lingering honeysuckle, depending on where you live.

Important note: I only cook with flowers from my own yard because I know that they haven’t been sprayed with herbicides or pesticides. If you use flowers from another property (or even on your own if your neighbor uses chemical treatments), be aware that you may be ingesting something harmful to your health.[1]

Violet Syrup

The genus Viola includes 500-600 species of violets and similar flowers, found mostly in the northern hemisphere. If you were born in February, violet is your birth flower. If you live in Illinois, Rhode Island, New Jersey, or Wisconsin, violet is your state flower. The kinds you might find in your yard are usually blue or purple in color, but they come in a range of hues, achieved through breeding.

Violets have been used for perfume, making use of an interesting feature of their natural chemistry: the compound ionone temporarily desensitizes receptors in the nose, making you physically incapable of detecting additional violet scent until your nerves recover. This feature makes it seem like the violet’s scent comes and goes.[2]

Violets can be used in cooking as well. My mom used to make candied violets using sugar and egg white, and I remember decorating a cake with them for a cast party when I was in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I was excited to try my hand at this syrup, which is straightforward but very time-consuming. (It took the better part of a day to pick and then stem the two cups of flowers I used in this recipe.)

Ingredients:

- 1 part violets, with stems and calyxes (the green part) removed

- 1 part water

- 1 part granulated sugar

Process:

Pour boiling water over violets in a non-reactive dish (Pyrex works just fine), cover, and let sit for 24 hours.

Strain violets and squeeze any remaining water out of them.

Pour violet infusion into a double boiler (or into a small bowl placed on top of a saucepan with an inch or two of water in it) and add sugar. Heat and stir until sugar is dissolved.

Pour into a bottle/jar/other container to refrigerate – or seal in canning jars to make your syrup shelf-stable.

And what, you might ask, do you do with violet syrup? You can use it to flavor desserts or drinks. While there are some recipes better suited to high tea, my preference was to use it for a cocktail. And so, I added it to my favorite drink: a gin and tonic…

Violet Gin & Tonic

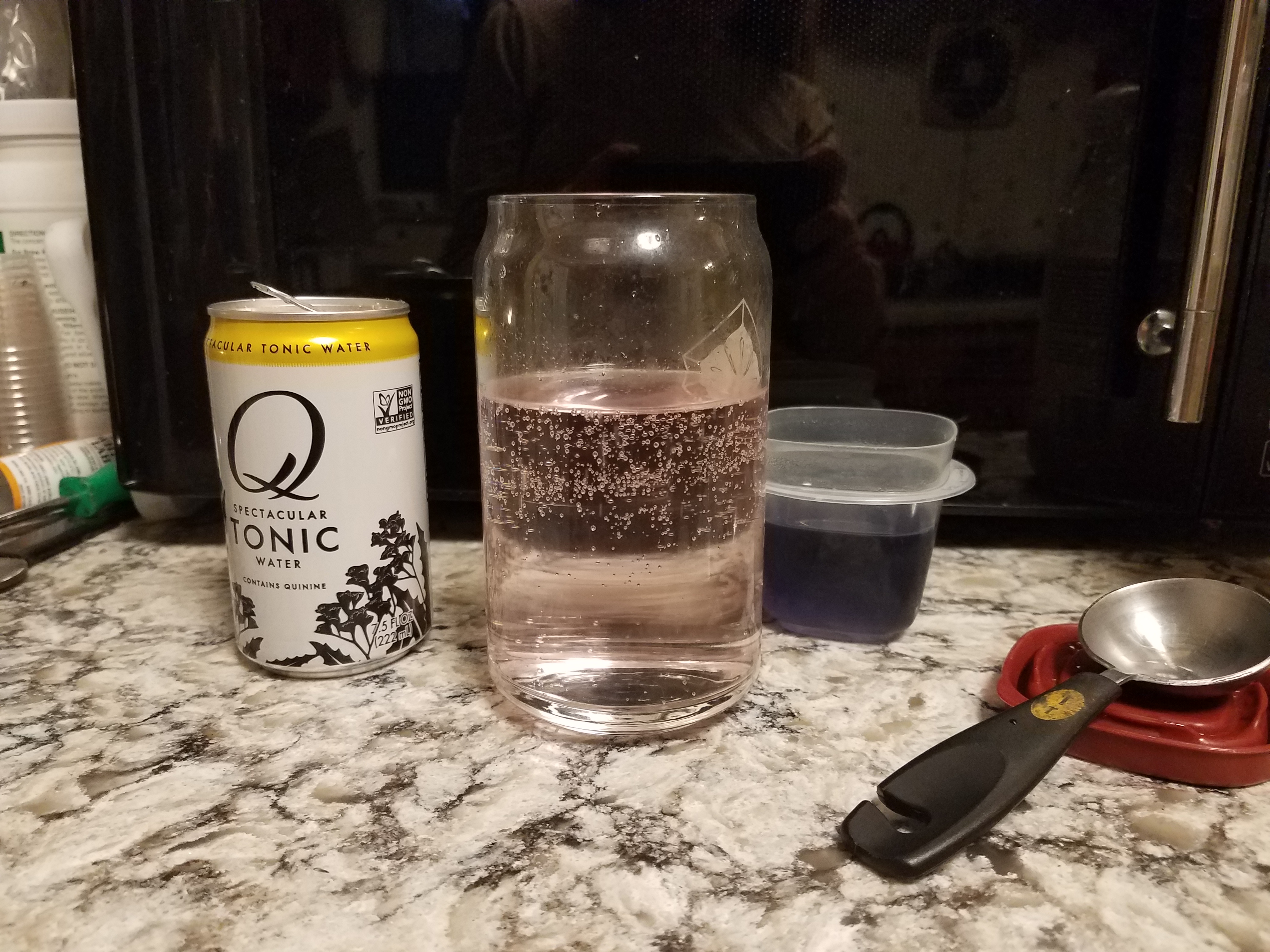

Even more enjoyable than the taste of this drink was the chemistry aspect. Violets contain antioxidants called anthrocyanins: they are one of the reasons why violets have been used for medicinal purposes throughout history, but they are also why the pH of your drink will affect its color. “The anthocyanin turns red-pink in acids (pH 1-6), reddish-purple in neutral solutions (pH 7) and green in alkaline or basic solutions (pH 8-14).”[3]

I can confirm that the tonic I use is acidic because I watched my drink change from blue to pinkish-purple as I added the tonic to the glass.

Ingredients:

- 2 Tbs violet syrup

- 2 oz gin

- 8 oz tonic water (I prefer the brands that use real sugar instead of high fructose corn syrup)

Process:

Shake and pour over ice. Garnish with a violet or – if you’re feeling particularly ambitious – freeze violet petals in ice cubes for when you serve the drink. How much violet syrup you use will depend on how sweet you like your drink and how vibrant a shade of purple you want.

Honeysuckle Syrup Recipe

Next I moved onto honeysuckle. There are 180 species of honeysuckle in the northern hemisphere, but the one you’re most likely to see around here is Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), which is aggressive and invasive.[4] If you’re not careful, it will choke out other plants around it. If you’re really not careful, it will become a tree – we have one in our yard, and it’s the only one I’ve ever seen. Although it is considered an invasive species, it does feed a variety of creatures, including moths, hummingbirds, and humans. I love the little drop of nectar you can get from the base of the flower – it tastes like summer to me.

Ingredients:

- 1 part honeysuckle – use the orange blooms, not the white ones, with the calyxes (green part) removed

- 1 part water

- 1 part granulated sugar

Process:

Pour boiling water over honeysuckle in a non-reactive dish (again, I use a Pyrex bowl), cover, and let sit until cool.

Strain blossoms and squeeze any remaining water out of them.

Pour honeysuckle infusion into a double boiler (or into a small bowl placed on top of a saucepan with an inch or two of water in it) and add sugar. Heat and stir until sugar is dissolved.

Pour into a bottle/jar/other container to refrigerate – or seal in canning jars to make your syrup shelf-stable.

As with the violet syrup, you can use this for desserts, but again, I decided to make myself a drink. Because of the subtlety of the flavor, I chose a gin cocktail – and a favorite one at that: The Bees Knees.

Honeysuckle Bees Knees

The Bees Knees is a Prohibition-era cocktail made with honey syrup (1:1 honey and water), gin, and lemon juice. Using honeysuckle syrup gives it a little more of a floral note. While the syrup by itself smells overpowering and (I must admit) slightly unpleasant, it made one of the best cocktails I’ve ever had.

Ingredients:

- 1 oz honeysuckle syrup

- 1 oz lemon juice

- 2 oz gin

Process:

Shake and pour over ice. Add a honeysuckle blossom on top if they’re still in season.

The proportions here depend on your taste, but I am not a fan of super-sweet drinks. Other recipes I’ve seen for Bees Knees use less gin to make the drink sweeter, but I typically halve the amount of sweeteners (or double the amount of alcohol). Just go with what tastes good to you.

Canning Instructions

If you want to keep the taste of spring throughout the year, you don’t have to worry about how long these syrups will keep in the refrigerator. All it takes is a little extra effort to seal them in canning jars, and they make great presents – or they can sit and wait until you’re ready for them. If you have never canned anything before, it is incredibly easy. But note that these seals don’t last forever, so always check the guaranteed time-frame on the packaging.

The key to canning is making sure that you keep the food product at a high enough temperature for a long enough time to kill the bacteria in the food.[5] You can confirm that you have done it correctly by checking the status of the lid over time. The heat from the process will force the air inside the jar to expand and escape through the lid, but as the jar cools, the lid will seal to the jar, forming a vacuum, and no air (or bacteria) will be able to get back in. If, for some reason, the seal is broken and bacteria does get in, the bacteria will grow and increase pressure on the lid, and the lid will pop up. You’ve seen this type of safety cap on commercial products, even if you’ve never eaten anything canned at home.

Most canning jars (which you can find at most well-stocked grocery stores or super-stores) have instructions on the packaging, and I would direct you to follow those specific steps. Regardless, they are always incredibly easy and do not require a lot of specialty equipment.[6]

~

I hope you get a chance to make some of these treats for yourself, if not this year, then next. I myself am looking forward to holding onto May for a little longer.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/roundup-and-glyphosate-part-1/

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viola_(plant)

[3] https://scialert.net/fulltext/?doi=jas.2011.2406.2410

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Honeysuckle

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pasteurization

[6] https://www.freshpreserving.com/blog?cid=water-bath-canning

0 Comments