It is Christmas Eve as this post goes live, and over the past couple years, Christmas Eve has meant surprise repair projects around the home. In 2020, our roof began to leak; in 2021, our driveway retaining wall collapsed; last year it was Christian himself who needed some repairs in the way of physical therapy; and this year we’re guessing it’s going to be our hot water heater, which is ready to shuffle loose its mortal heating coil.

Out with the Old

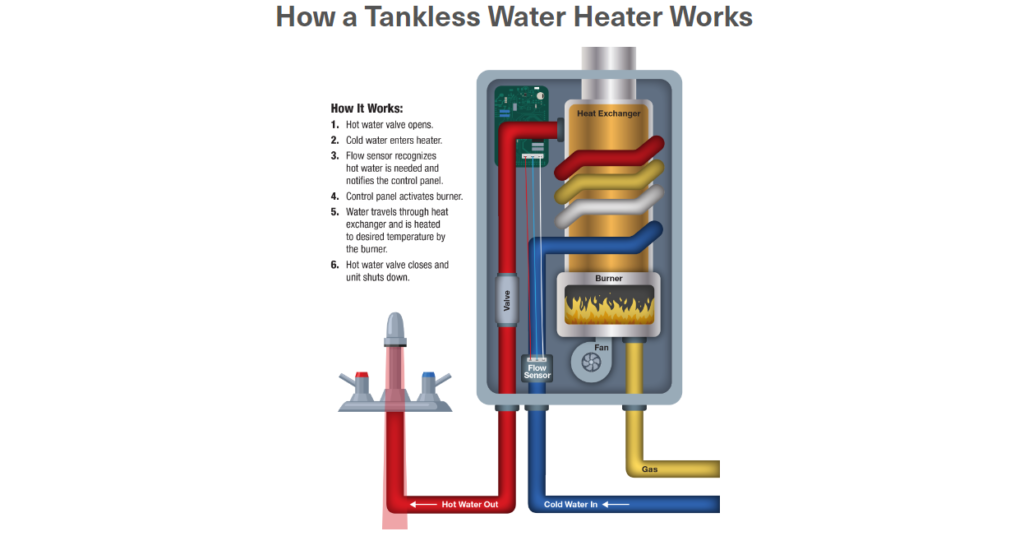

This appliance is old, and as with other aspects of this house and the things in it, I have been waiting for the opportunity to upgrade to something more efficient and environmentally friendly. Christian and I have chatted periodically about replacement options, but the time to make a decision is nearly upon us. We were both interested in getting a tankless water heater, given what we have heard about them being more energy efficient, which is true since they don’t have to heat and store water – they produce hot water on demand as it is needed in the house, eliminating standby energy use. The choice seemed clear, so the next logical step was to look at our options.

I assumed right off the bat that we would get an electric model, leap-frogging over a gas replacement to prepare for inevitable shifts toward whole-home electrification. [1] Since I am trying to reduce my use of fossil fuels overall, I didn’t even consider a gas model, and it wasn’t until I had a list of electric options evaluated and ready to go that I was presented the question of a gas alternative. I’ve gone into detail about our gas usage before on the blog: we have a gas furnace, clothes dryer, hot water heater, and a gas hookup for our grill. [2] While the furnace represents the biggest component of our demand, my calculations show that hot water represents about 15% of our total gas use, coming in at about 360 kg CO2-equivalent every year … 360 kg I was hoping to eliminate.

Image credit: [3]

But, in the name of fully evaluating our options and understanding the pros and cons of each before making a decision, I shelved my examination of specific electric models (for the moment) in order to examine a bigger-picture question. First, it was worth examining the priorities represented in this household. Those include: lowering our carbon footprint, using less gas, saving money, comfort and ease of use, resale value of the house, and getting some usable space back in the garage, where the existing tank water heater lives. It’s safe to say that using less gas and saving money represent the two most significant priorities in this case.

Gas Savings

Using less gas is inevitable either way if we go from tank to tankless because the design itself is more efficient. The Department of Energy lists a range of estimated energy savings from 24% to 34% for homes that use around 41 gallons or less of hot water per day. [4] (For reference, we use around 40 gallons per day on average, based on our bills, and about 28 gallons of hot water per day, based on a very, very rough estimation of when we do and don’t use hot water.) That range in potential savings can come from differences in appliance use but also from differences in the units available. In general, electric units tend to be more efficient than gas units, so in my calculations to compare them, I put the electric model at the high end of savings and the gas unit at the low end.

If we bought a gas unit, we would probably be using around 75% of the gas we are using now to heat our water, say 270 kg CO2e / year. The question of gas savings is trickier with a switch to the electric model: over half of the electricity made in Pennsylvania comes from gas, meaning that we would still be burning gas to power our electric hot water heater, having simply moved the point of combustion from our house to a generation plant. Given our current grid mix of about 54% gas and 10% coal, [5] powering an electric appliance (including a car!) from your default electricity provider still represents about 1/3 of a kilogram (or 3/4 of a pound) of CO2e for every kilowatt-hour used. For that reason, switching to an electric heater without switching our source of energy generation would not achieve as much of a payoff from a carbon footprint standpoint as it would appear on the surface. We would probably still be coming in at over 120 kg CO2e / year for hot water.

Image credit: [6]

Of course, there is an option available to us here to offset the burning fossil fuels altogether, and that’s an option we took in the spring of 2022: third party electricity supply from renewable generation. (I’ve got extensive posts on third party suppliers [7] and their importance for energy independence [8] on the blog, which I encourage you to read for more background.) Unfortunately, just a few months after we switched to a company I had thoroughly and painstakingly vetted, they discontinued their service, and we were moved back to our local provider. I haven’t yet picked a replacement, but that will be a priority in conjunction with this water heater decision, regardless of what we decide … which brings us to the other major factor in all of these environmentally friendly decisions: the price tag.

Dollar Savings

The biggest and most obvious concern in this evaluation was the cost of electricity compared to gas. Both fluctuate over time, but electricity tends to be more expensive, sometimes significantly so. But because of that volatility, it can be difficult to create a fair comparison, particularly when examining a long-term investment. According to one source, 2023 pricing for electricity in Pennsylvania has been around 2.4 times more expensive than gas, [9] though the bills I used in my recent weatherization analysis showed electricity to be a little over 3 times more expensive during the last two years at our house. [10] The calculations I did for this exercise used rates from our local providers’ websites, which also got us to a factor of about 3.

Given that energy prices (particularly gas prices) are so volatile, it is difficult to predict what long-term costs will be, especially along the 20-year lifetime of the unit. That said, I found a source suggesting that a 3% increase for gas every year is a reasonable assumption. [11] Alternately, many analyses expect prices of renewable energy to drop as supply increases and technology improves, [12] but I’m not optimistic enough to reduce electricity rates in this calculation. To be conservative, I kept my renewable electricity prices steady over the time period. In the end, the safest statement is to say that no one really knows how prices will play out, particularly when you start adding things like renewable subsidies and carbon taxes, but an educated guess is sometimes all we have.

Image credit: [13]

For more reliable numbers in a price comparison, we can look at upfront costs, and that’s where the electric option definitely wins out. Electric units themselves are cheaper than their gas equivalents (by what seems to be around $500), and it appears that installation costs can be significantly lower too, as gas installations require proper flow of gas and ventilation of exhaust for the unit to be effective and safe. Both require some annual maintenance when it comes to filtering water (particularly hard water), but it appears that gas units also need annual inspection to ensure safe fuel combustion and operation. [14]

Ultimately the question was whether the cheaper initial installation and lifetime maintenance of the electric unit outweighed the cheaper operation of the gas unit. And the result was… unclear. In fact, a net present value calculation over 20 years put both options roughly in the same ballpark, even when coupling the electric unit with a switch to renewable energy. Of course, there were plenty of assumptions in there, and tweaking those assumptions sometimes put the gas unit ahead and sometimes put the electric unit ahead. But I am fine with that – my hope was that the electric unit wouldn’t be so much more expensive as to make it economically unfeasible, and that does not appear to be the case.

~

In summary, I am glad I took this detour to examine our options in more detail, rather than simply assume I was pushing for a course of action that was more environmentally friendly but also more costly. After this exercise, I am much more confident in recommending the electric unit to help meet our financial needs and philosophical goals, and I hope our current water heater holds out long enough for us to examine specific options and make some informed decisions. (Though, given our track record with December 24, we may be showering at my in-laws’ house…)

Do you have a tankless water heater? What do you like (or not like) about it? What should someone know before investing? I’d love to hear about your experiences below.

Thanks for reading!

Keep reading about our electrification journey –>

[1] https://www.environmentenergyleader.com/2023/08/the-whole-home-electrification-is-gaining-steam/

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/weatherization-update-gas-savings/

[3] https://youtu.be/Hik2eRgO5BU?si=sq2P6xzsaP2RC8e5&t=77

[4] https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/tankless-or-demand-type-water-heaters

[5] https://www.eia.gov/state/analysis.php?sid=PA

[7] https://radicalmoderate.online/third-party-electricity-suppliers-part-1/

[8] https://radicalmoderate.online/renewable-energy-and-energy-independence-part-1

[9] https://shrinkthatfootprint.com/natural-gas-heat-vs-electrical-heat/

[10] https://radicalmoderate.online/weatherization-update-cost-savings/

[11] https://primexbt.com/for-traders/natural-gas-price-prediction-forecast/

[12] https://www.energy.gov/eere/wind/articles/driving-force-projecting-offshore-wind-energy-costs

[13] https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/tankless-or-demand-type-water-heaters

[14] https://www.gotankless.com/compare-gas-electric-tankless.html

0 Comments