It pains me to think about how close we are to the end of summer, as this post goes live, but it wouldn’t be summer without the ubiquitous, blood-sucking, itch-inducing, disease-carrying pests that are mosquitoes. On one hand, I recognize that all animals are living creatures, and I do not revel in ending anything’s life. On the other hand, there are instances where I recognize the need to suck it up and do what needs to be done. Those few cases include things like spotted lanternflies,[1] termites,[2] fleas (post coming soon), and this week’s subject.

A major concern with mosquitoes is not simply that their bites leave itchy spots, but that some of them they can carry serious diseases, such as malaria (carried by genus Anopheles),[3] West Nile virus (carried by genus Culex),[4] and Zika (carried by genus Aedes).[5] Of course, it’s not their fault – they’re just trying to survive, too – but knowing the serious impacts these diseases can cause, I have little compunction when I swat and kill. It’s also important to note that mosquito populations are increasing significantly, meaning the associated risks of vector-borne diseases are also on the rise.

Rising Risks

Climate change is often cited as the reason for increasing mosquito populations. While that can be the case for other types of insects, such as ticks, a recent study conducted in New York, New Jersey, and California showed no significant correlation between mosquito populations and temperature, or – surprisingly – between mosquito populations and long-term precipitation trends. It was actually the declining presence of chemicals such as DDT and increased urbanization that most closely correlated with the rise of mosquito populations.[6]

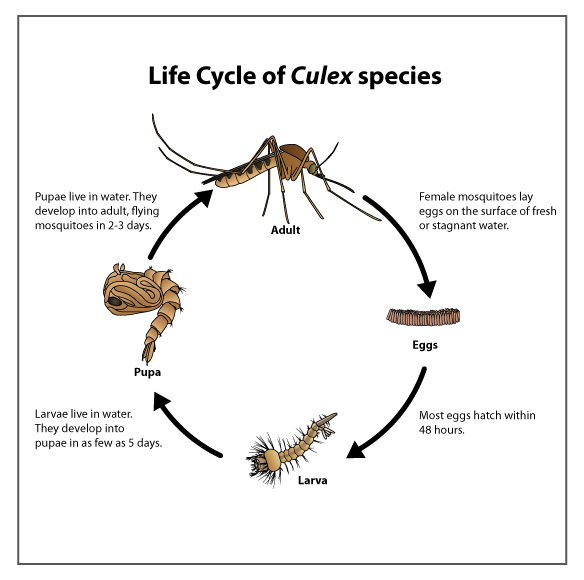

There are over 3,500 species of mosquitoes, and specifics vary, but they go through four developmental stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. This cycle can take from five to 40 days, depending on species characteristics, ambient temperature, crowding and food availability in the breeding grounds, and other environmental conditions. This cycle can take longer if, for example, eggs are frozen over the winter or dry out in periods without rain – some species can pick right back up when conditions become optimal again.

Life Cycle

Adult males typically live about one week, feeding on nectar and other natural sugars. Females can live up to four weeks in captivity, but average about one to two in the wild. They do feed on nectar as well, but typically need the protein, iron, and other nutrients in blood to develop and/or lay eggs. Females lay eggs in or near the water, and the eggs hatch into larvae, which feed almost constantly on algae and biological material. Although larvae live in the water, they breathe air through spiracles (I prefer “snorkels”) at the end of their long, segmented abdomens, so they stay close to the surface. Pupae are more shrimp-like in appearance and do not eat, but rather spend their time developing before they molt and emerge as adults. And the cycle repeats.[8]

Given their need for water, I personally expected our warmer, wetter weather to be playing a much larger role in this mosquito boom, with longer seasons in which to live and reproduce, as well as more breeding locations created by increased precipitation. However, ecosystems are complex things, and correlation does not necessarily mean causation. More impervious surfaces in urban areas and more habitat disruption for their natural predators are much more significant factors contributing to the rise of their population. (Unfortunately, after extensive research,[9] I was very disappointed to find there is no good place on our house to put a bat box, which would definitely help address the problem.)

If you, like me, cannot bring in bats as a very effective natural bug service, there are some things you can do to help reduce mosquito breeding grounds on your own property. Mosquitoes need standing water to reproduce, and that can mean fish ponds, bird baths, impermeable surfaces that collect water, and even bromeliads.[11] I had been more than a little overdue in changing out the water in my birdbath recently, and it was full of wriggling mosquito larvae. Birdbath water should be changed at least once a week. As for ponds, consider adding fish that eat mosquito larvae, such as gambusia.

Attracting & Repelling

I have noted, from personal experience, that I do not suffer from the bulk of the mosquito bites when I am out with friends. Certainly, if I’m sitting on the porch or gardening on my own, I’ll get dive-bombed constantly, but in groups, I tend to be relatively unbothered. I’ve wondered about this trend since a study abroad trip to Ecuador in college, when I went home with only a handful of bites, but my poor roommate had over 80 (we lost count). Even when hanging out with my parents, my mom will get most of the bites, while my dad and I seem to be less popular.

There is some truth to this trend, as examined in multiple studies over the years. Mosquitoes in labs do tend to prefer Type O blood,[12] though anecdotally, I can also say that they also prefer Type B to Type A. In addition to blood type, there are other factors that can attract mosquitoes, such as heavy breathing and sweating (both of which happen while I am gardening). There is also information that indicates the presence of certain types microbacteria colonies on the skin, which contribute to body odor, can make humans more or less attractive to mosquitoes.[13]

All this is to say that – similar to the reasons why mosquito population growth is on the rise – there are multiple factors at play as to why they may be attracted to some people more than others. In the meantime, we can at least do our best to discourage them from chasing us around our yards. I’ve never encountered a sure-fire way to keep them off of me (aside from hanging out with Type O and Type A people, a.k.a. “bait”), but there are a few things that at least help more than they harm. If you want to use a more natural alternative for protection than conventional bug spray, look for products containing these ingredients or follow the link here for some recipes to make your own repellant:[15]

- Lemon eucalyptus oil

- Crushed lavender flowers

- Cinnamon oil

- Thyme oil / thyme leaves (in campfire)

- Catmint and catnip oil

- Soybean oil

- Citronella

- Tea tree oil

- Geraniol

- Neem oil

Of course, it’s important to note that there are always priorities to consider, especially when traveling to areas that are high in vector-borne diseases. More traditional synthetic insect repellants can be more effective, but you may be concerned about safety with prolonged use. Even with natural alternatives like the ones listed above, it is important to use caution, as they too can cause skin irritation if used in high enough concentration.

I’ll simply close with my personal favorite when it comes to mosquito repellant, which did not appear on the list above: garlic. Whether camping in the Amazon or West Virginia, I have had excellent success after consuming massive amounts of garlic on a daily basis. It keeps the mosquitoes away – along with everyone else.

~

Do you have any tried-and-true mosquito repellant tips? I’d love to hear about them below.

Wishing you a bite-free remainder of summer. Thanks for reading!

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/spotted-lanternfly-101/

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/integrated-pest-management-termites/

[3] https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/malaria/index.html

[4] https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/

[6] https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms13604

[7] https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/about/life-cycles/culex.html

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosquito

[9] https://radicalmoderate.online/birthday-bat-box/

[10] https://abilitymagazine.com/mosquito-control-and-mosquitofish/

[11] https://bromeliadparadise.com/blogs/care/how-to-get-rid-of-mosquitoes-in-bromeliads

[12] https://www.healthline.com/health/mosquito-blood-type

[13] https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0028991

[14] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dUytFZpoAHk

[15] https://www.healthline.com/health/kinds-of-natural-mosquito-repellant

0 Comments