When I saw my first total solar eclipse in 2008, I knew it wouldn’t be my last. I had put it on my bucket list largely out of academic interest, but the experience itself was primal, even spiritual, with very little of my intellect engaged during the key 100 seconds of totality. It was almost a decade before I saw my second and another seven years until I saw my third (with an annular eclipse tossed in there for good measure. [1]) When these events come around, I am reminded of some important life lessons that are all too easily forgotten in the intervening time – aspects of our lives that might benefit from a more cosmic-level perspective.

“You can’t always get what you want”

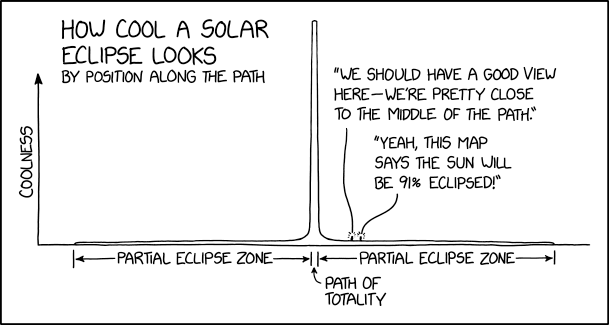

I will not mince words here: there is no comparison between a total solar eclipse and an almost-total solar eclipse. The first time I stood in the moon’s shadow, looking at what appeared to be a hole in the sky, I experienced terror on a cellular level. Of course I knew – intellectually – that I was not in danger, but I completely understood – after the fact – how early civilizations could have imagined that the world was coming to an end. And that isn’t a feeling you get on either side of totality, when you can’t simply stare at the sky, eyes unprotected, wondering why the sun isn’t where it is supposed to be.

Image credit: [2]

And that fundamental difference was why I was shocked to see so many articles and comments in early April 2024 that were seemingly encouraging people not to make such a big deal out of totality. One writer talked about how viewing a partial eclipse was a cool but not life-changing experience, so it wasn’t worth getting all worked up about spending so much time and money to try to go see a total. [3] (I felt myself wanting to shout at my screen “it wasn’t life-changing because you only saw a partial!”) Now, I know there are people who don’t agree with me about what an amazing experience it is, my husband being one of them, but I was very clear with my team at work that I would be taking April 8 off to drive wherever I needed to, and that they should too if they wanted. Only one other person took off that day.

But if the ultimate point of these seemingly contrarian, click-baity hot-takes is that you should still take the time to see a partial if you can’t see a total, I would agree with that. I know people who had to work and people who couldn’t travel, and in those cases, yes, they got a different experience, but still a cool one – one that can still feed a love of astronomy and a sense of wonder about our world, as did the partial eclipse I saw in fourth grade.

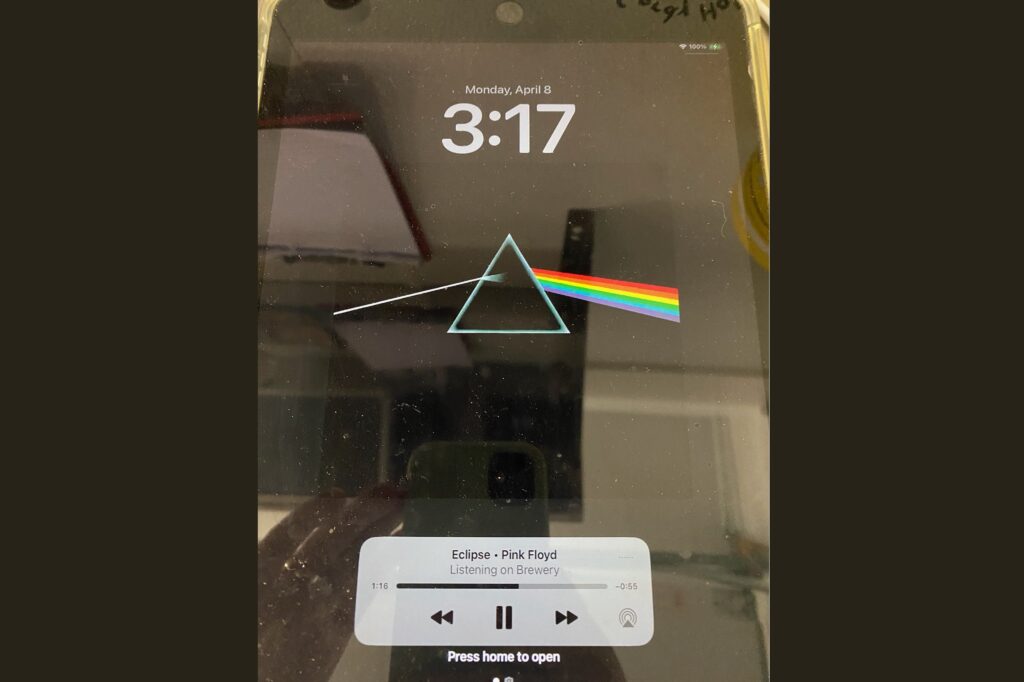

And in such cases there are still things that you can do to break out of the day-to-day routine and enjoy the rare and special occasion that it is: our office building in Pittsburgh had black-and-white cookies and eclipse glasses for everyone who came in that day; my best friend (further north, at about 99% totality) took a break from work at the appropriate time and went outside to see as much as he could while playing “Dark Side of the Moon” over the speakers; one of my coworkers wound up watching it from his porch, admiring crescent-shaped shadows on the ground… and also listening to “Dark Side of the Moon.”

Image credit: Galen Osby

So, yes, there is absolutely a great reminder here for all of us: in these examples there was an aspect of enjoying what you have even if you can’t get what you want. But there was also, in my case that day, the inverse: an aspect of getting what you want and not enjoying it (or at least not to the extent I felt I should have).

“And now’s the time, the time is now”

2024 has certainly not played out as I expected, which is why I had barely given the eclipse a thought until April 8 was close enough to be in the weather forecast. Since several viewing locations were drivable from Pittsburgh, I decided to wait until there was a sense of weather conditions in Cleveland, Erie, and places further southwest and northeast. While the weather is unpredictable and represents an element of chance for any eclipse, there was other prep work I could have done – but didn’t – in the lead-up to the day. I did not order the solar filter for my camera as intended, I did not research camera settings or practice doing composite shots (which didn’t work last fall in Utah), I don’t even think I checked my camera battery until the morning of.

Consequently, my departure was a little disorganized and a little late, with my progress further delayed by the Erie-bound traffic I encountered on I-79. Weather forecasts informed me that I would have a lower chance of cloud cover the further southwest I went along the path of totality, but by the time I was heading south on I-71 in Ohio, eyeing cirrus clouds overhead, it was becoming a game of chicken: how long would I be willing to drive, balancing eclipse start time with better conditions? By the time I pulled off the highway near Mansfield and drove along miles of country roads until I found an abandoned parking lot where I was reasonably certain I wouldn’t be asked to leave, the eclipse had already started. It took me time to set up my camp chair and tripod, cover myself in sunblock (ironically still necessary), dissect a pair of eclipse glasses to tape to my camera lens, and play with my camera settings until I found something that I liked. (I used an aperture of f/4.5, which is notably not what NASA recommends [4] and a shutter speed of 1/500 second.)

Image credit: Jess Cockburn

In addition to fiddling with my DSLR’s “solar filter” and manual settings, I was also documenting the event with my cell phone: capturing images of my amusing but now traditional half-assed camera setup, my Sky Map app creepily showing all of the planets plus our sun and moon in the same part of the sky, and myself, sporting my “Astronomy is looking up” t-shirt and solar binoculars. While I was struggling to complete all of this self-assigned prep work, the moon’s progress across the disc of the sun only seemed to accelerate, and I felt like I barely had enough time to get excited.

The last sliver of orange sun seemed to pause and hold its breath as I switched between my eclipse glasses, solar binoculars, and camera screen for the best view. Then finally, the field in which I sat slipped into shadow; I peeled the electrical tape off my lens and spent the next three and a half minutes taking photos. Because Venus and Jupiter were visible to the naked eye, I tried to capture them on my camera, hoping to pull them into a composite shot, but my aperture and shutter settings, while perfect for the eclipse, didn’t capture the planets, so I tried to adjust those on the fly before switching back to my cell phone, which didn’t have a wide enough angle to capture everything in one shot, which necessitated a video recording – and I might as well get a 360-degree video of the twilight on the horizon while I was taking video.

Because I had “so much time” with the luxury of a long eclipse, I told myself that I would still be able to enjoy the spectacle once I got all the shots I wanted. Thankfully, I did pause for a few seconds in the middle of it all to look up when switching between camera and cell phone – because that was all I got, and it was all over before I knew what was happening. That briefest of moments when I was huddled over my equipment, then turned and looked up over my shoulder – at the very thing I was there to see – took my breath, as it always does. The video I captured proves that there were noises, but all I remember is an eerie quiet so profound that my ears seemed to ring, while the silvery corona silently shimmered in the middle of a black sky, daring me to stop what I was doing and just take it all in.

Image from Sky Map: [6]

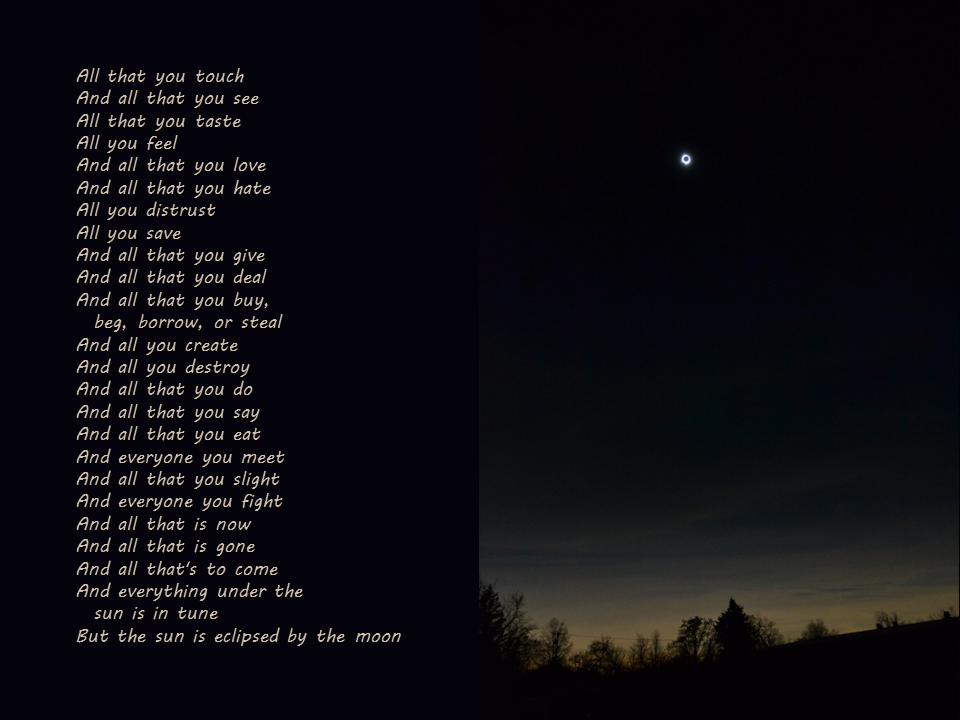

“Everything under the sun is in tune…”

Now, I will say I got a really cool shot – something I had never tried before, and I was really happy with how it turned out – but it did come at the expense of me being in the moment. I had a 12-hour round-trip that day, with about 10 of those hours behind the wheel of my car, and easily less than 5 seconds of my attention spent actually looking at the total eclipse without a camera between me and the moon. I absolutely understand the desire to capture the moment – we do so much of it in our daily lives, whether it’s holding on to an ephemeral moment or performing for social media. I have spent the vast majority of my adult life trying to capture moments I want to remember while also enjoying the artistic aspect of creating something beautiful. But that doesn’t change the fact that if I’m observing the moment, I’m not experiencing it – and that’s a hard thing to square, especially when you love photography.

I absolutely know that part of my desire to capture the eclipse was to share with others something that means so much to me. And because this one was visible so close to Pittsburgh, I was thrilled that so many of my friends were able to go see it. (For years I had told my mom that I was going to get her to come out here so she could see one herself, but that didn’t happen. I like to think that she saw it… or something even cooler while zipping around the cosmos.) Having worked at an observatory, astronomical events are inherently social occasions – a time to celebrate and recognize our connection with each other on this “pale blue dot,” as Carl Sagan put it. [7]

And I now know so many people who have experienced their first total eclipse and described feeling a stronger bond with others during and afterwards, whether it was with the people watching in the same location or more broadly with the rest of humanity. Part of that perspective, I think, comes from being reminded that we are not the center of the universe, that we’re all on this tiny planet together, and that even our greatest wars seem petty when considering how inconsequentially small Earth is in the context of everything else that has ever existed. But it’s also inspiring, when thinking about the movement and evolution of everything in the cosmos, that we are all made from elements created within stars billions of years ago that then formed new stars, and planets, and us – tying us to each other and to the universe in ways we tend not to think about on a daily basis. [8]

Lyrics by Roger Waters [9]; photo by Alison Steele

It feels like a shame that some of us (like myself) need a cosmic event to gain a little cosmic perspective in our daily lives, but that may just be human nature. This most recent eclipse has reminded me of some important life lessons, and I’d like to hope that we can do a better job of remembering them until the next one (which may be as soon as two years from now for me, [10] but at least 20 years for some parts of the US.) With that thought, I will close this extra-long, extra-philosophical post with the words used at the end of ABC’s coverage of the 1979 eclipse, looking ahead to the next one in far-off 2017: “may the shadow of the moon fall on a world at peace.” [11]

Thank you for reading.

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/the-music-of-the-spheres/

[3] https://slate.com/technology/2024/04/reasons-to-see-just-partial-eclipse.html

[4] https://www.nasa.gov/science-research/five-tips-from-nasa-for-photographing-a-total-solar-eclipse

[5] https://whenisthenexteclipse.com/what-happens-if-its-a-cloudy-eclipse/

[6] https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.google.android.stardroid&hl=en_US

[7] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GO5FwsblpT8

[8] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y4pCl0MWNa0

[9] https://genius.com/Pink-floyd-eclipse-lyrics

[10] https://www.visiticeland.com/article/iceland-solar-eclipse-2026

[11] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gAacZoIJUN0

1 Comment

rjwarren59c8cb9109c0 · August 12, 2024 at 1:56 pm

It’s time for you to write a book❤️

I love reading your work. Never fails to amaze me.