We’ve been all over the place in this series, from the breaker panel in my home, [1] to the global transformer shortage, [2] to consumer usage trends that inform how we’re building our electrical grid. [3] To tie these disparate threads back together in the last post on this subject (for now), it is important to consider a few things:

- There are some electricity needs that do have to be met at certain times;

- For everything else, shifting those activities can help increase the reliability of our grid;

- Adjusting our behavior to recognize and respond to existing limitations does not have to be a hardship and can, in fact, have financial benefits

Smoothing Demand

Given very real constraints in expanding – and possibly even maintaining – our existing electrical grid, we can’t ignore the reality of restricted electricity supply in the future, especially as demand continues to increase. (Of course, it already happens occasionally in the United States, but I have traveled to countries where blackouts or rolling brownouts are such a common occurrence that no one even bats an eye when they happen.) Similar to the example of the tourist town in last week’s post, [4] we can consider what components of our demand can and cannot shift throughout the day in order to limit strain during high-demand times.

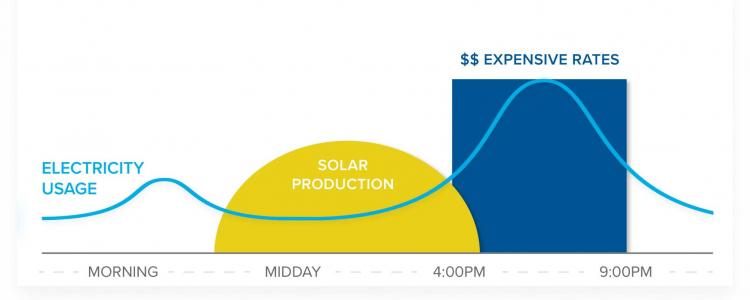

Many utilities across the country already offer Time of Use pricing to encourage users to think ahead and plan for when they will need electricity to support certain tasks by providing discounts during off-peak hours. [5] I feel like I have seen more examples of that practice in commercial and industrial sectors, where individual customers can use massive amounts of energy in short periods of time, but I also feel like I am seeing more of it over time in the residential sector as well, like promotions offering free electricity overnight. [6] It has been a few years since I worked in this space, but my general impression is that it is still costs less for the electric distribution company to offer rebates and discounts for changes in equipment and behavior, respectively, than it does to build additional capacity to support that demand.

Image credit: [7]

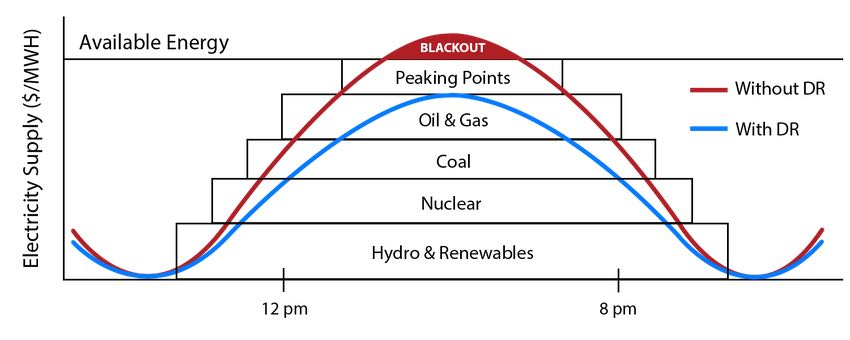

Time of Use pricing is generally a passive incentive – if you know about it and want to save some money, you might choose to take advantage of it if and when you remember. There are more active scenarios (referred to as “Demand Response”) in which a utility might ask customers (via a text or app notification) to limit their own usage in real time when it appears that demand will outpace supply, such as on a hot afternoon in the summer when everyone turns on their air conditioning at the same time. That may not be, for example, the best time to charge your car if you’re not going anywhere or do your laundry if you’ve got something else to wear. And, though I live with someone who might disagree with this statement, adjusting your thermostat to 76 degrees isn’t a major hardship if it’s normally set to 74.

Cause and Effect

One of the biggest obstacles I have noticed in shifting the technologies we use and/or how we use them is our own perceptions about what we actually need. I often (too often) see conversations about our energy use devolve into exaggerated, unrealistic, pathos-heavy scenarios in which we have no agency in our own homes, and our quality of life declines into that of a developing country. Having just returned from a developing country, I can tell you that I survived not having air conditioning (or any electricity for that matter) in the middle of the afternoon when it was over 90 degrees F and over 90% humidity.

To be clear, I am not saying don’t use your air conditioning. I recognize that not everyone has the heat tolerance I do, and I absolutely recognize that access to air conditioning in hot weather is increasingly becoming an equity issue, in which people who can’t afford it experience greater risks to their health and safety as temperatures continue to rise. In the United States alone, we are seeing more heat-related deaths every summer, [8] and here in the US we are currently less impacted by and better equipped to deal with episodes extreme heat than many countries across the globe.

Image credit: [9]

And global impacts are important to remember when considering the following: electricity generation shifts with how much demand there is at any given time. Sources that are less nimble (e.g. nuclear) stay on for more of the time, providing constant power, while sources that can start and stop more quickly are used to provide more power when we need more power. The latter, referred to as “peaker plants,” often rely on fossil fuels, which release climate-warming carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere. I have often mused on the irony of this feedback loop in which we cool ourselves with air conditioning powered by fossil fuels, which raises temperatures so we need more air conditioning.

I personally feel better knowing that we’re using less electricity than we were before weatherizing our attic [10] and that whatever fossil-based electricity we’re using is being offset with renewable energy credits, [11] but I also know that many, many people are not in the position to be able to afford weatherization, renewable energy, or even air conditioning to start with. And because of that, smoothing our electricity demand is a critical piece of the complex puzzle that protects people in the short term (by ensuring safe conditions during extreme weather) and – ideally – in the long term too by limiting the effects of climate change.

A False Dichotomy

And that brings us back to this issue of perception when it comes to what we need vs. what we use. I regularly hear arguments from proponents of fossil fuels that simplify the situation into a binary dichotomy of “fossil fuels = abundance; renewable energy = hardship.” Those opinions fuel a mentality that we shouldn’t have to give anything up, and that fossil fuels will ensure that we don’t. But the reality is that over time – whether in our lifetimes or our grandchildren’s lifetimes, whether we proactively transition away from or simply run out of them – we will be using fewer fossil-based sources of energy and more renewables.

Image credit: [12]

That is not hopeful thinking on my part, but a simple fact since we are using fossil fuels faster than they are being replenished – therefore there will ultimately be an end point. If we resist change now because someone tells us it will be a hardship, there will absolutely be more significant hardships for people in the future who are unprepared for increased climate impacts and/or the sudden scarcity of the fuels that caused them. Whenever that turning point happens, we can be prepared or unprepared for it – and I can tell you which I’d rather be.

I don’t intend to come off as preachy in this post, but it is necessary for us to consider the options before us. Ultimately, can we balance short-term and long-term needs – for ourselves, for humanity, and for the planet – by understanding the impacts of our choices? It probably sounds ridiculous coming from someone with an MBA (especially one who got an A in marketing) because the entire field of marketing is based on getting people to recognize a need (whether it’s legitimate, exaggerated, or completely manufactured). But this is the time when we should be asking ourselves questions like “do I need this thing, or do I want it?” “do I need it now, or can it wait?” – and from an electricity standpoint, it could just mean waiting a few hours to start your dishwasher.

Given existing and (likely) future electrical grid constraints, we need to be examining ways to use our current infrastructure more effectively – and things like demand-smoothing programs can help make that happen. I would encourage you to take a look at your electricity bill or your electricity supplier’s website to see if they offer Time of Use pricing or Demand Response options. You may be able to help save the world while you save some money. And if those programs aren’t available to you, even just evaluating your use on your own could still help you identify ways to use less electricity and save some money (and, by extension, the world).

~

There will be plenty more to come in future posts about mechanisms to coordinate all of the supply sources, storage options, and user behavior associated with our electrical grid. But for now, what questions do you still have? What insight can you share about your own experiences? Please add to the comments below!

And thanks for reading!

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/electrical-service-upgrade/

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/more-than-meets-the-eye/

[3] https://radicalmoderate.online/planning-around-grid-capacity/

[4] https://radicalmoderate.online/planning-around-grid-capacity/

[5] https://www.papowerswitch.com/understanding-energy/about-rates-terms/time-of-use/

[7] https://www.sunrun.com/go-solar-center/solar-terms/definition/time-of-use

[9] https://www.protoolreviews.com/demand-response-programs-legislation/

[10] https://radicalmoderate.online/weatherization-update-electricity-savings-part-2/

[11] https://radicalmoderate.online/renewable-energy-and-energy-independence-part-2

0 Comments