Part 3 – Processing Food

Several weeks ago when I began researching this topic, I posted a comment on Facebook about how shocked I was to learn about the heavy greenhouse gas footprint of cheese. Judging by the nearly 100 shocked comments from friends in the following days, I was not alone in my ignorance. I have known for years that reducing meat intake is a great way to lower one’s carbon footprint, and that going vegan is even better for the planet. However, I had always seen meat as the biggest factor, with dairy an incremental step.

In addition to learning that cheese was far worse for the environment than chicken or pork, I also learned that local sourcing of food and packaging – some of my biggest factors in ethical food shopping for years – play a relatively tiny role in lowering your carbon footprint. Last year in my meatless meat blog series, I even went so far as to wonder if locally-grown grass-fed beef would have a smaller impact on the environment than soybeans imported from South America.[1] While I noted that additional research would be necessary, my hypothesis could not have been more wrong.

There are definitely benefits to buying local and in-season, and we will look at those in the coming weeks, but it is important to reiterate that the type of food you eat is the most critical factor in reducing your food footprint: cutting out red meat and cheese one day a week will create more of a benefit on that front than buying only local food.[2]

Processing Footprint

From “Our World in Data,” the same website referenced in the last two installments regarding the environmental impacts of different life cycle stages of food, we can see that processing makes up a relatively small percentage of the total footprint. According to the comprehensive global study, “processing” refers to “emissions from energy use in the process of converting raw agricultural products into final food items.”[3]

Image credit: [4]

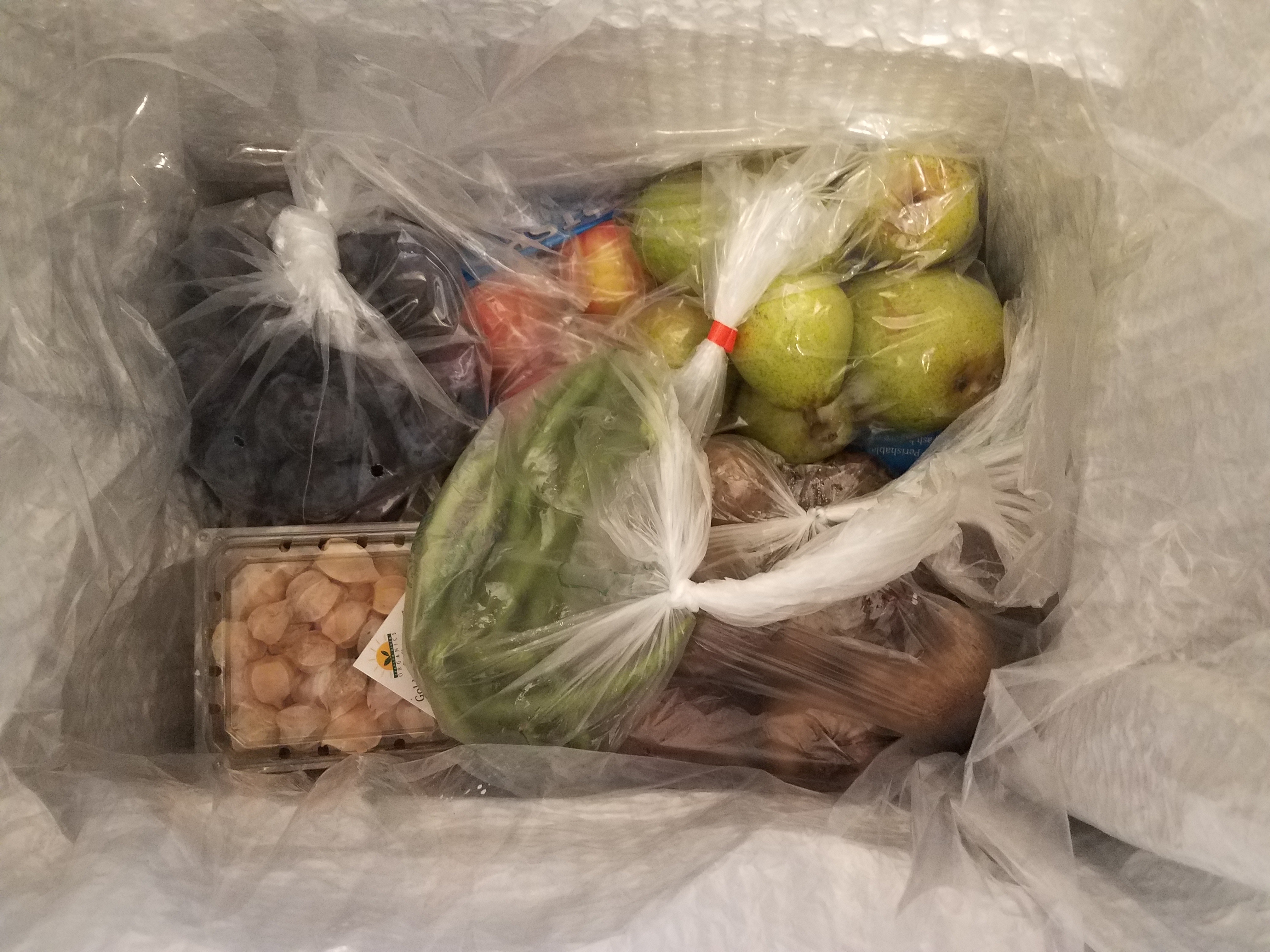

Beef and lamb/mutton require the most energy by weight for processing, along with palm oil. Tofu, cheese, and olive oil are up there too. Our CSA produce is understandably at the bottom of the list again, as it goes almost straight into the box after being picked, sometimes without even being washed.

For years, I’ve heard (and participated in) arguments about why processed food is bad for your health. I’ve also participated in food challenges that require the elimination of “processed food.” While it is not always clear in the guidelines of these challenges what constitutes “processed food” or why it should be eliminated, my general understanding is that there is a range of what can be considered “processing.” Some processing (as with fermenting cheese or pressing seeds for oil) is necessary to create the food item, or even to make them safer for consumption (as is the case with pasteurization). On the other end of the spectrum, you can see heavily processed prepared food items (such as cookies, chips, etc.), and that often involves adding salt, fat, sugar, and preservatives.

The idea is that the less processed the foods are, the more control you have over what goes into them (and consequently into your body) as you prepare them. According to the UK’s National Health Service, “buying processed foods can lead to people eating more than the recommended amounts of sugar, salt and fat as they may not be aware of how much has been added to the food they are buying and eating. These foods can also be higher in calories due to the high amounts of added sugar or fat in them.”[5]

Given this argument, CSA offerings, which are farm-fresh and generally do not include prepared foods (though ours has bread and cheese), are healthier to consume, but they also have a lower carbon footprint associated with processing. A study on “current Swedish food consumption patterns” showed that “Up to a third of the total energy inputs [of food options] is related to snacks, sweets and drinks, items with little nutritional value.”[6] Our CSA forces me to cook with minimally-processed foods, promoting healthy eating and also resulting in a lower carbon footprint.

Packaging Footprint

In full disclosure, our subscription gives the option of adding things like eggs, milk, cheese, and meat, but the cheese is likely the most-processed item of the bunch; the meat is simply butchered and vacuum sealed in plastic. When we got our first box, it was the plastic jug for the milk (not the milk) and the plastic wrap around the beef (not the beef) that made me question continuing with the subscription. To their credit, the reverse logistics are well organized: their delivery drivers pick up the old box, foil bags, and ice packs to reuse when they drop off the new box. The plastic bags can be recycled at our local grocery store, but reusing and recycling plastic packaging is still not as good as avoiding it in the first place.

While concerns about single-use plastics should certainly factor into any purchasing decision, I do find it interesting that plastic waste was the one and only reason I refrained from purchasing any cheese during Plastic Free July.[7] From a greenhouse gas standpoint alone, the cheese is far worse for the environment than the plastic that surrounds it, but the plastic packaging remains the thing that gives me pause when I am at the store. Old habits die hard, I suppose.

The packaging footprint in Our World in Data includes “emissions from the production of packaging materials, material transport, and end-of-life disposal.” While the packaging footprint makes up a small component of total GHGs associated with our food, it’s important to keep in mind that the type of packaging used (glass vs. plastic) or the presence of packaging in the first place still make a difference. Again, these numbers are shown as kilograms of CO2e per kilogram of food product, but remember that frequency and amount of consumption vary by food type: a pound of beef is different from a pound of coffee.

Speaking of coffee, it’s at the top of the list for packaging footprint, but that shouldn’t be too surprising given the thick bags used to keep the beans fresh for as long as possible. Oils, wine, and beer, often involve heavy glass bottles, which, while arguably more sustainable than plastic on the production side, will have a higher carbon footprint associated with transportation. Meats, tofu, and cheese are next and usually involve some kind of plastic wrap. Veggies are at the bottom again – while they sometimes come in plastic, packaging materials are certainly not necessary.[8]

Next week we will continue by looking at some of the other factors that play into the pros and cons of CSAs, including the impacts of food waste. To help you limit your own food waste, I’ll leave you with another recipe that can use a variety of vegetables that play supporting roles to a vegan protein.

Toss It All In: Recipe

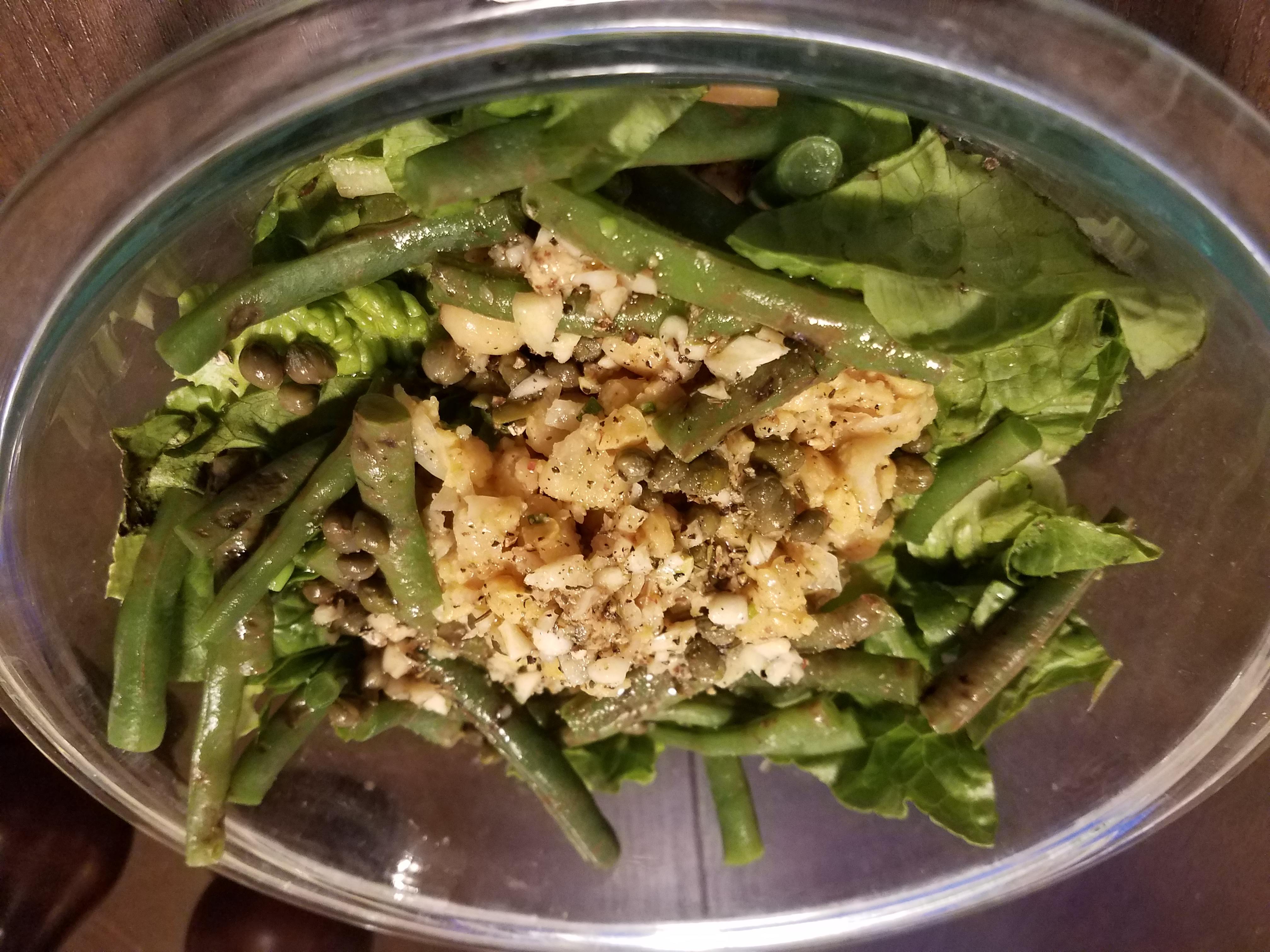

I don’t eat nearly enough salads, even though that’s what I’m best set up for with my CSA. When I manage to get organized enough and actually make it happen, they’re delicious – especially this one, which is based on a favorite of my mom’s and mine: Tuna Niçoise.

The original recipe involves tuna, and the last time I ate it was the summer before I left for college (the last time I ate tuna, if I remember correctly). This “tuna” substitute using chickpeas provides a tasty protein centerpiece, while the rest of the salad acts as a supporting role – meaning that it matters less which other ingredients are available, allowing some flexibility based on what shows up in your CSA in a given week.

Sure, depending on what you put in or leave out, it may no longer be — strictly speaking — Niçoise, but ultimately we’re trying to make something tasty, not accurate. The recipe below is summarized and adapted from Minimalist Baker.[9]

“Tuna” Niçoise

“Tuna”:

- 15 oz can of chickpeas

- 1 tsp dijon mustard

- 1 tsp maple syrup

- 1 pinch salt

- 1 Tbs caper juice

Salad:

- 1 head lettuce

- 1/2 c Niçoise, green, or kalamata olives

- 1/4 c capers

- 6 small red or yellow potatoes (optional)

- 1 c trimmed green beans (optional)

- 1/2 c sliced tomato (optional)

- 1/2 grated or sliced red beet (very optional)

Dressing:

- 3 Tbs minced shallot (or garlic if you don’t have it)

- 1 tsp dijon mustard

- 1 tsp fresh thyme

- 1/3 c white or red wine vinegar

- 1/4 c olive oil

- 1/4 tsp each salt and pepper

Mash “tuna” ingredients together and season to taste. Boil potatoes (10-12 minutes) and green beans (2-4 minutes) if using them. Combine dressing ingredients and whisk or shake to combine. Arrange lettuce and salad toppings in bowl, spoon “tuna” into the center, top with dressing, and season with salt and pepper.

~

Have you cut out or cut back on any foods because of their carbon footprint? Do you have any substitutes that do the trick? Feel free to share your suggestions and recipes below.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/beyond-impossible-meatless-meat-part-3/

[2] https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es702969f

[3] https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food

[4] https://www.change.org/p/woolworths-and-coles-supermarkets-stop-wrapping-small-portions-of-herbs-vegetables-and-fruit-in-plastic-and-styrofoam

[5] https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/what-are-processed-foods/

[6] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0921800902002616

[7] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-corona-edition-part-3/

[8] https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food

[9] https://minimalistbaker.com/vegan-nicoise-salad/

3 Comments

Charles Korey · December 6, 2020 at 4:03 pm

I Believe it was Linda McCartney who championed the meatless diet. Paul followed her lead.

Alison · December 7, 2020 at 5:00 pm

The way Paul tells the story, they arrived at that conclusion together while eating lamb… and watching their lambs run around outside.

“the type of food you eat is the most critical factor in reducing your food footprint” – The Bethlehem Gadfly · December 10, 2020 at 2:01 pm

[…] Community Supported Agriculture, Part 3 […]