Part 2

“Only the paradox comes anywhere near to comprehending the fullness of life.”

– Carl Jung

[This post contains spoilers for “Princess Mononoke”]

The characters in Hayao Miyazaki’s movies are complex, as are the worlds in which they reside. In last week’s post, we looked at the attributes of his heroines, as full and flawed as they are, but it’s not just character complexity that I find fascinating: it’s how much Miyazaki leans into the concept of paradox, both in his characters and in his settings. One of my favorite things about Miyazaki’s movies is that there isn’t a whole lot of “good vs. evil” polarity, and the result is not just a richer story but a more realistic and relatable one.

For example, in “Princess Mononoke,” there isn’t an outright villain, at least not among the main characters. [1] There are opposing forces between the human and spirit worlds, which creates the tension of the story, but even the obvious antagonist, Lady Eboshi, is not evil. While Eboshi’s goals include clearing the forest and (ultimately) killing the Forest Spirit, she also provides work and housing for society’s outcasts, including lepers and former sex workers, all of whom love her for her kindness to them and admire her for her leadership skills.

Image credit: [2]

It would have been very easy for Miyazaki to set up the story as more clearly binary, with good San and the forest spirits fighting for their home against an evil captain of industry – and certainly, that’s how I viewed it the first time. The introduction of a third party, Prince Ashitaka, who wishes “to see with eyes unclouded by hate,” guides the audience to a different perspective: one in which we can see that while San and Eboshi are fighting each other, each believes to be doing what is right. By the end of the movie (or maybe after a couple viewings), we the audience can come to see each side (even if we don’t necessarily agree with one or the other) and even understand Ashitaka’s choice to remain connected to both at the end of the movie.

A Man of Contradictions

This lack of good/bad polarization and even win/lose scenarios stems from the complexities and paradoxical nature of Miyazaki himself. Born to an affluent family in Tokyo in 1941, his youth was shaped by the events of WWII, during which his family was evacuated multiple times. [3] An outspoken pacifist, feminist, and environmentalist, he creates movies that don’t come off as preachy. On the contrary, he fully leans into an approach of illustrating the context and motivations of his various characters, which specifically limits our ability (in most cases) to label them as “good” or “bad,” as is the case for the vast majority of people, once you get to know them. And that makes for a much more rewarding experience for the audience, too.

I’m not going to say that stories with “good vs. bad” melodrama and narrative conclusiveness (i.e. one side clearly winning over the other) don’t have their role. (As a lifelong “Star Wars” fan, I fundamentally can’t say that.) But they also make for a lazy audience. More complex characters are more realistic, and more complex stories force us to think about the situation, particularly as we feel certain threads resonate within our own lives. While escapist cinema is no doubt fun, stories that lean into paradox, that force us to recognize that two conflicting ideas can both be true at the same time, are a more accurate reflection of the world in which we live. Contradictions and paradoxes are inherent in human nature – that’s not just OK to recognize, it’s actually beneficial for us to explore as a concept.

Image credit: [4]

In an episode of Brené Brown’s podcast on the subject of paradox, Barack Obama spoke a lot about navigating the space in which two opposing concepts can both be true. In that conversation, he described characteristics of people who tend to be more comfortable operating in ambiguous spaces – I was thrilled that among his examples were liberal arts majors who work in business (hello!) and scientists who are also spiritual (hi, again!). [5] I personally love the challenge of thinking larger than my own perspective, knowing that I don’t have it all in my head, and figuring out how to navigate that “third space,” as it is called in Jungian circles. I don’t see paradox as contradictory; I see it as an opportunity to expand my perspective.

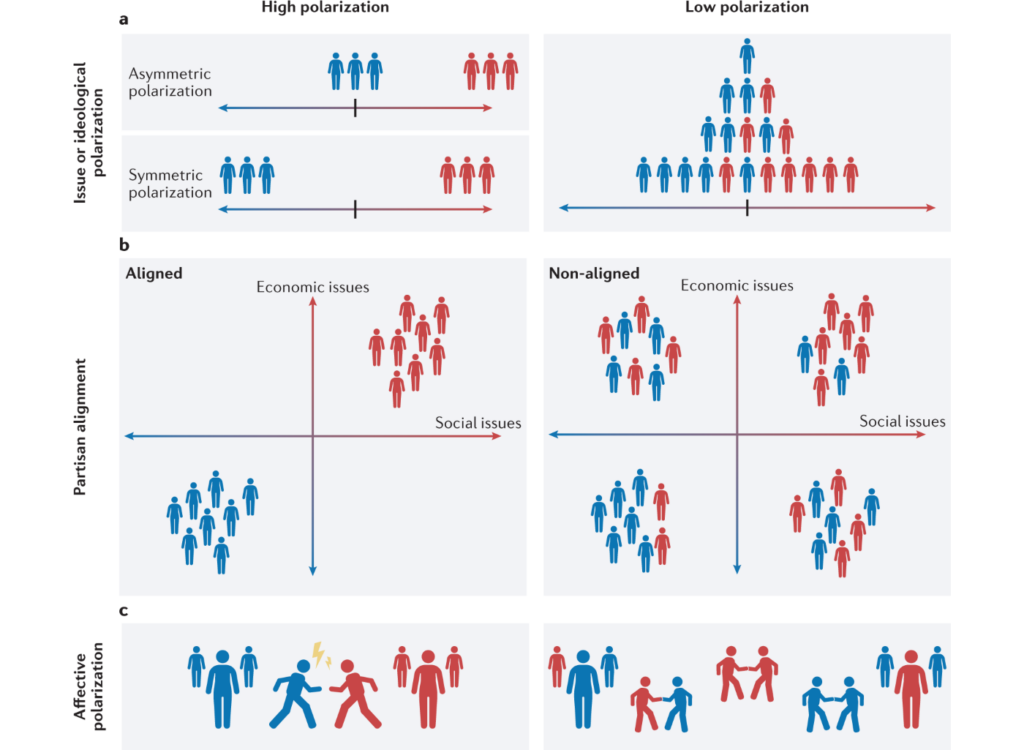

The Urge to Simplify

Unfortunately, it takes time, energy, and vulnerability to lean into that uncomfortable space. Many of us don’t have the bandwidth or desire to do that. Humans are inclined to put in less effort and optimize ease whenever possible – and unfortunately from a storytelling (and story-hearing) standpoint, that leads to increasingly polarized thinking. The opposite of paradox is polarization, as relationship therapist Esther Perel stated in another episode of Brené’s podcast that focused on paradox. [6] That conversation laid out a concept that I have explored before, but never so explicitly: when there are two opposing parties, each becomes increasingly defined by the other. As they become more polarized, it becomes easier to define the other as the opposite, particularly when it comes to morality (i.e. the more we see ourselves as good, the more we see the other camp – by definition – as bad).

But here’s the interesting part: as Miyazaki clearly states, no one is 100% one thing or the other; similarly, Esther Perel explains that we all exist somewhere on a continuum of any personal attributes or beliefs – and those shift over time. If you look at a relationship (romantic or otherwise) between two people (or groups), one position begins to define the other, and vice-versa. That happens because, although we exist somewhere on a given continuum, we start to “split the paradox” within us, hold on to one piece, and assign the other piece to the other party. And the more we retreat into those polarized identities, we suppress our own complexity by counting on the “other” side to represent that missing part of our personality, or identity, or role. She also explains that when you don’t have an “other” there to fill that role (i.e. an outlet for offloading the other side of that paradox), then that complexity returns.

Image credit: [7]

Holding space for paradox does result in some interesting conversations when speaking with people who are working from a narrower perspective. For example, I feel like I am likely to explore aspects of spirituality when speaking with someone who is more science-oriented; to bring up scientific principles when a conversation veers toward truthiness instead of fact; to advocate for environmental and social considerations of business decisions, not just looking at the bottom line; or to examine the financial feasibility of more environmentally and socially sound business practices. It’s not a matter of being contrarian or playing Devil’s Advocate for fun; it’s more a matter of raising relevant perspectives that I feel haven’t yet been considered.

Leaning Into Discomfort

Because of that state of duality, your own role can vary depending on the role of the “other” party. For instance, Miyazaki’s movie “The Wind Rises,” which is about the engineer who designed the Mitsubishi Zero (the fighter plane used in WWII), earned him criticism from both sides: because of the subject matter, he was accused by some of glorifying weapons of war, but because of his own pacifist ideals, which permeate his work, he was also accused of being anti-military. To hear him talk, he clearly embraces the contradiction of recognizing the beauty of engineering and also the consequences of inventing technology that causes destruction. [8] It’s also clear that he uses film as a medium to explore his own feelings within the space of various paradoxes (much as I use this blog to do the same.)

Clearly Miyazaki is not trying to play to the middle and make everyone happy – he has admitted to intentionally creating movies that certain audiences would hate. Good art makes us uncomfortable because it forces us to expand our perspectives and consider how we as individuals feel, not how we are supposed to feel as we identify with a certain group. In Obama’s podcast appearance, he noted the increased assimilation of political platforms over time. Specifically, we are seeing more pressure for those who identify with a certain political party to accept all of the party’s platform planks in order to be a true member of that party, which was not the case in decades past. As political identity becomes more closely tied to political doctrine, it becomes harder to hold a slightly different opinion or even question an assumption within one’s defined group.

Image credit: [9]

The key to moving forward, at least as we can see in Miyazaki’s movies, is listening and looking for context instead of applying labels, identifying common values that can be used as a starting point to build harmony instead of achieve victory over the other. Part of the issue is the polarization between opposing camps that are uncomfortable exploring the continuum they share, but the other part of the issue is the idea of some kind of final victory in a situation that will only continue to evolve over time, whether we like it or not. Ashitaka sees that two opposing ideas can be true and that he doesn’t have to pick sides: he takes on the role of going between both worlds, visiting San in the forest and helping Eboshi rebuild Iron Town. There will continue to be a tension between man and nature, but the story is left open without a clear winner or loser.

~

Unfortunately, it can be difficult for many of us to imagine a resolution without a winner, and we’ll get into one of the reasons why next week. Until then, I’d love to hear your thoughts here, particularly what I’m missing or getting wrong.

Thanks for reading – and sharing your thoughts!

Keep Reading About Miyazaki –>

[1] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0119698/

[2] https://mononokehime.fandom.com/wiki/Ashitaka?file=Wa18.jpg

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hayao_Miyazaki

[4] https://www.nature.com/articles/s44159-022-00093-5

[5] https://brenebrown.com/podcast/brene-with-president-barack-obama-on-leadership-family-and-service/

[6] https://brenebrown.com/podcast/partnerships-patterns-and-paradoxical-relationships/

[7] https://x.com/elementalmeme/status/466242905070264320

[8] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UG6XzB_J3IA

[9] https://recoverynet.ca/2013/09/17/i-contain-multitudes-walt-whitman/

0 Comments