Thank you for being here! I can’t believe it has been six years since the inaugural post of Radical Moderate. [1] Over 300 posts later, my goal is still to examine issues related to sustainability by diving into the details of complex situations. This consistent research and writing has given me the opportunity to learn more about a wide range of topics but also to examine how I feel about them. And if you have gained any value here, that’s very satisfying gravy for me.

In Radical Moderate anniversary tradition, we’ll be addressing a topic related to the corresponding wedding anniversary gift [2] – in this case, iron… or a very specific substance made from it: steel. (For the record, I consider that to be a completely valid substitution – my husband, who has some metallurgical expertise, bought me stainless steel kitchen equipment for our Iron Anniversary.)

When it comes to steel… I am from a steel town, I moved to a steel town, I’m a Steelers fan, and my last name is Steele, so this topic does feel a little on-the-nose for me in many ways, not to mention that some of the points I’ll make in this post overlap with issues I address as part of my day job. Just a reminder that – as always – the content of this blog is my own and does not represent the positions of any organization with which I am associated.

“Iron and coke, chromium steel”

The steelworks in my hometown was once one of the largest manufacturers in the world, and its steel contributed to famous buildings and bridges across the country, railroads and freight cars, the Hoover Dam, and more than 1,000 naval ships that were used to defeat the Axis powers in World War II. [3] I absolutely understand the pride that comes with hailing from a steel town, even when (or especially when) that industry, which provided the backbone of our country’s infrastructure, is in decline. The United States, once the world leader, produced 79 million of the 1.9 billion tons of steel made globally in 2024, coming in fourth after China, India, and Japan (more on that later). [4]

Image credit: [5]

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon, but other elements (e.g. chromium, vanadium, etc.) may be added to create other alloys with various desirable properties. Although steel manufacturing boomed beginning in the mid-1800s, it had been produced throughout the world for centuries prior. Iron has several beneficial attributes, such as thermal and electrical conductivity, that make it useful in certain applications, but steel is harder and stronger, making it a better choice as a structural material. Several methods of production have evolved over the last century to optimize control over the process, efficiency, and cost, but at its core, steelmaking consists of burning off impurities and excess carbon from iron ore until the desired percentage of carbon (in the ballpark of 1%) is reached. [6]

A common component of steelmaking is coke, which is produced by baking pulverized coal in coke ovens at around 2,000 degrees F in the absence of oxygen. This process, called “pyrolysis,” drives off organic material and water, resulting in a cinder-like material of essentially pure carbon. Coke can then be added to a blast furnace along with iron ore and lime to produce molten iron. The coke serves several functions: it acts as fuel to create heat and melt the ore, it provides carbon to produce the desired metal, and it helps to remove oxygen from the ore. When coke burns, it creates carbon monoxide; when carbon monoxide is present in a blast furnace with iron oxide, the two interact, resulting in iron and carbon dioxide as outputs, like so (for anyone who remembers chemical equations from high school):

Fe2O3 + 3CO → 2Fe + 3CO2

(iron oxide + 3 carbon monoxide → 2 iron + 3 carbon dioxide) [7]

Up in the Air

Although I grew up within smelling-distance of a coke works, and I currently live within smelling-distance of another, I didn’t actually understand the specifics of its function in steelmaking until writing this blog post. (I always assumed that coke was used only to add carbon to iron, not to help remove oxygen from iron ore.) Nor did I get the joke when the Lehigh Valley named its minor league baseball team the IronPigs. (“Pig iron” is the name of the intermediary material created after iron ore is smelted with coke – it still needs more carbon burned off to become steel.) But whether nearby residents understand the chemistry of the process or not, we know when it’s happening.

Image credit: [8]

The Clairton Coke Works, owned by US Steel Corporation, is the largest coking facility in North America and sits along the banks of the Monongahela River, southeast of Pittsburgh. The odor of rotten eggs and chemicals is not a new experience for me or anyone who lives or works in that river valley, but what many may not realize is that along with the sulfur smell come hazardous chemicals, including benzene, toluene, mercury, lead, and others. [9] There are regulations in place to limit the amount of hazardous emissions from the facility, but those are exceeded regularly, resulting in a raft of notices, fines, and suits against US Steel. [10]

Upriver toward Pittsburgh in Braddock Township is the Edgar Thomson Works, one of the oldest steel mills in the world, employing some steelworkers whose fathers and grandfathers worked at the same site. Together with the Coke Works and the nearby Irvin steel mill, the Edgar Thomson Works has contributed to thousands of air quality violations by US Steel Corporation in the Mon Valley and represents a focus for cleanup efforts among environmental groups who are concerned about health impacts of poor air quality as well as climate impacts of greenhouse gas emissions. [11]

In the Hothouse

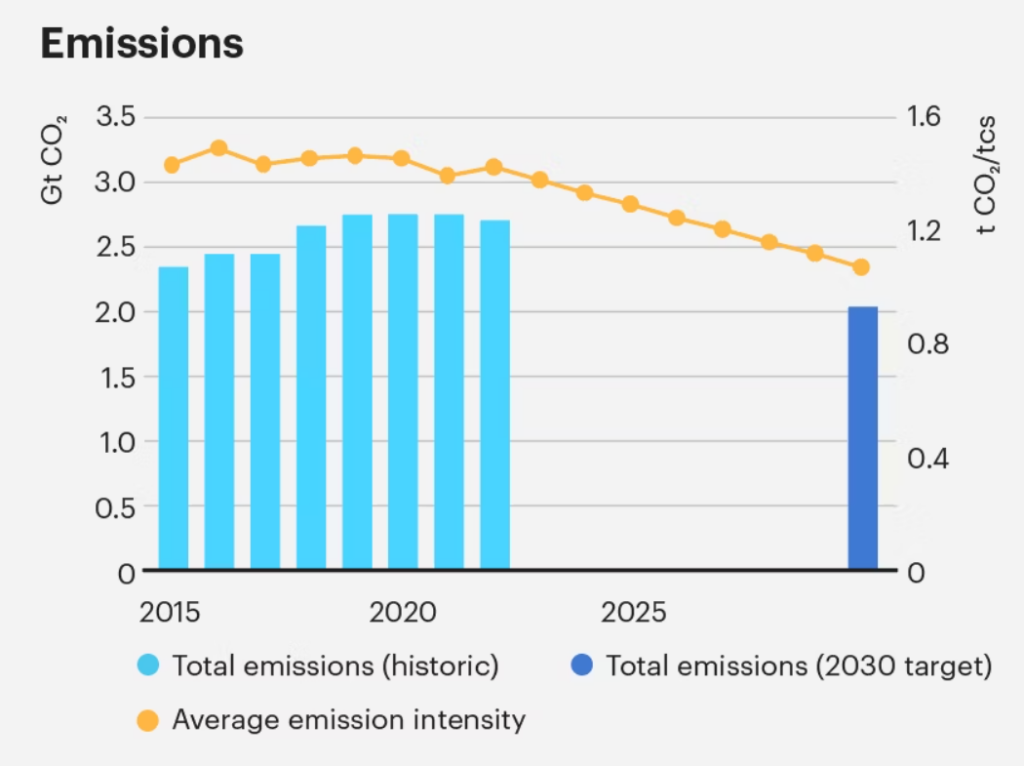

Steelmaking is one of the most carbon-intensive manufacturing processes in the world, owing to its reliance on coal, both to generate necessary heat and to act as a reducing agent in the chemical process described above. In 2018, steelmaking represented about 8% of global carbon emissions, with 1.85 tons of CO2 emitted for every ton of steel produced. [12] Today, that global percentage has been quoted at closer to 10% – although some incremental improvements have reduced the direct CO2 emissions associated with steelmaking, it is still an incredibly hard-to-decarbonize industry, and global demand for the product is still on the rise. [13]

Image credit: [14]

There has been a lot of uncertainty about national-level decisions since the Trump administration took office in January – both how we govern ourselves and how we work with other countries in a global society. Although our president has decided to remove us from the Paris Climate Agreement (again), there are factors other than Paris that are pushing the steel sector toward decarbonization, as noted in a 2020 analysis from McKinsey: increased customer pressure for carbon-friendly steel products, tighter regulations on carbon emissions (notably in Europe), and increased investor interest in financial sustainability (i.e. wanting the steel industry to remain viable in the long term, in the face of climate change). [15] Our self-styled financial genius of a president may pooh-pooh any talk of industrial decarbonization, but there is absolutely a strong business case for pursuing it.

At the moment, we are seeing some early examples of reduced carbon intensity in steelmaking through the use of hydrogen fuel as opposed to fossil fuels. One producer in Sweden is moving in this direction, converting natural gas-fired furnaces to hydrogen. Though it is an expensive change, with carbon pricing in place in Europe, steel made with renewable fuels will be cost-competitive with the conventional alternative. [16] It is important to note that there are different ways to source hydrogen as a fuel source, which we covered in an earlier post on this blog, [17] and these facilities in Sweden are using “green” hydrogen (made through electrolysis powered by renewable energy), not “blue” hydrogen (made through steam reformation of methane – a fossil fuel – with carbon capture technology).

Bringing it Home

It should go without saying that these efforts in Sweden will first and foremost serve as a proof of concept for the rest of the world, and that financial factors will play a huge role in the speed of adoption elsewhere. The same McKinsey analysis referenced above stated that production costs for green hydrogen were expected to reach parity with the cheapest and most prevalent form of hydrogen production (steam methane reformation without carbon capture, or “gray” hydrogen) by 2030. This equalization would be a result of technological improvements in the green hydrogen process, leading to declining costs, as well as increased penalties associated with CO2 emissions. [18] I heard a similar statistic at an energy conference two years ago, but we can’t expect much in the way of financial incentives for renewable energy or disincentives for fossil fuel use within our borders over the next four years, and I’m not sure to what extent US-based decisions will impact global market and innovation trends on this front.

Image credit: [19]

When it comes to steelmaking in the United States, Pittsburgh has been in the headlines for over a year due to the proposed $15B buyout of US Steel by Nippon Steel. When I traveled to Japan last fall as part of my climate program, the deal was one of the first things people asked me about once they learned I was from Pittsburgh. The debate has raged during that time about pros and cons of the move, with US Steel Corporation being in favor of the acquisition and the United Steelworkers union opposed. [20] In a rare example of alignment from the US political arena, President Biden (who blocked the deal near the end of his term) and then-President-Elect Trump both opposed the deal. [21]

If the whiplash-inducing pace in the news of late is any indication, all bets are off in the days, months, and years to come with respect to final decisions. However, on February 7 (two days prior to this post), President Trump announced that there would be an investment in, not acquisition of, US Steel by Nippon Steel, adding that he would “mediate and arbitrate” the terms. [22] Meanwhile, another acquisition bid is on the table from American company Cleveland Cliffs, but with the original agreement locked up in court proceedings, it is unclear when and how things will shake out. But no matter the buyer, I imagine that any purchase will likely result in one of the following scenarios for the trio of facilities that make up the Mon Valley Works:

- A massive investment supporting an upgrade to sustainable, low-carbon technology to make Pittsburgh a pioneer in the steel industry once again (the chances of which I believe are near zero, especially with Trump mediating any negotiations);

- A modest investment supporting retrofits that favor gas-fired processes when upgrades are necessary to keep production limping along as cost-effectively as possible for the time being (which is far more likely, especially given presidential preference for the natural gas industry); or

- No meaningful investment, which would signal the beginning of the end of steel in Pittsburgh: a departure of US Steel’s headquarters from the region and eventual shuttering of the facilities (which is definitely not outside the realm of possibility).

Watching the end of steelmaking in Bethlehem in the 1990s and Bethlehem Steel’s bankruptcy and sale in the early 2000s, I know what the loss of industry means – both from an economic perspective and from an identity perspective. Working in the field of public health, I know that polluting industries are not in the best interest of the people who live nearby or for people who live across the globe when it comes to impacts from climate change. Having an MBA in sustainable business practices, I know that short-term earnings can often be at extreme odds with long-term financial responsibility, but that the long-term view, though harder to achieve, can help avoid the boom-and-bust cycles that tend to define the economic prospects of industrial areas.

~

Wrapping up this extra-long anniversary post on a topic near and dear to my heart, all I really have to show at this point is a summary of where things stand as of the day and time of this post… and a hope for holistic, forward-thinking decisions that meaningfully address the concerns of those who will be most directly affected. How will this decision affect you? I would be honored to hear your perspective.

Thank you for reading.

Many thanks to those close to me with chemistry and metallurgical expertise (notably my husband, my best friend, and my best friend’s dad) for checking some of my summaries and sweeping generalizations about the steelmaking process!

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/new-recycling-guidelines-in-the-south-hills/

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/tag/anniversary/

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bethlehem_Steel

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_steel_production

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bethlehem_Steel#/media/File:Bethlehem_Steel.jpg

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steelmaking

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coke_(fuel)

[10] https://www.wesa.fm/environment-energy/2024-02-28/allegheny-county-fines-us-steel-air-quality

[13] https://www.iea.org/energy-system/industry/steel

[14] https://www.iea.org/reports/breakthrough-agenda-report-2023/steel

[17] https://radicalmoderate.online/hydrogens-rainbow/

[21] https://www.wesa.fm/economy-business/2025-01-03/pittsburgh-us-steel-sale-nippon-biden

[22] https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/07/us/politics/trump-nippon-steel-us.html

1 Comment

Garrod · February 10, 2025 at 4:49 am

Yet annother extremely informative blog post! I learn something from every blog, Thank you for your hard work and research into each subject.