In our house we can’t believe the year is half over, the summer is in full swing, and we’re already into another year of “Plastic Free July.” I realized it was July last Thursday (the first of the month) while we were out for dinner and my food arrived, complete with little plastic cups of salsa and sour cream. Needless to say, my plastic-free month was not off to a great start, and the subsequent two days weren’t any better.

I’ve justified my surprising accumulation of plastic waste over the first three days of the month with the fact that we’re supporting local restaurants, which we know took a hard hit during the past year. As I mentioned in last year’s Plastic Free July introductory post, I recognize that Styrofoam is a cheap option for small businesses, and that my desire to “vote with my dollar” and avoid restaurants offering takeout in Styrofoam helps the environment but damages their business. Given that, I’ve been allowing myself one takeout meal in Styrofoam a month during the pandemic, but even that gives me pause.

In this post, I intend to talk about some additional concerns regarding the creation of plastic, but I need to start with a big disclaimer: I try very hard to keep my work and personal lives separate – not just from a mental health standpoint, but for the sake of professionalism as well. As the head of a non-profit organization, I frequently need to be mindful about what I say in public, both when I’m representing my company and when I’m not. Therefore, because some of what I’m going to talk about here overlaps with some of what I do for work, I need to be clear that this post represents my personal opinions, and that I am not speaking on behalf of the organization I run.

The Plastic Supply Chain

I’ve talked in past years about concerns around plastic waste, specifically focusing on how little actually gets recycled (Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle should be done in that order)[2] and the sheer increase of single-use plastic during the pandemic.[3] The plastics industry has been behind a hard push over the last year arguing that we need single-use items to support health-protective measures, even though the risk of surface transmission is incredibly low for COVID-19.[4]

In my previous posts on the subject, I’ve focused on “downstream” impacts, specifically what happens to the plastic after we use it, such as when it takes up landfill space, when it winds up in waterways or the ocean, when sea life eats or chokes on it, or when tons of it is shipped to Asian countries where residents there are inundated with mountains of unrecyclable garbage.[5] This year (through my job and current events in the region), my focus has turned toward the “upstream” impacts, specifically what happens on the supply side.

Southwestern Pennsylvania has supplied energy resources for generations, be they from coal, oil, or gas. For the past ten years, hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking” has been a contentious issue, with some arguing that it is an economic boon to the region, and others arguing that the negative environmental and health impacts will outweigh any potential benefits. Interestingly, the economic argument seems to be showing holes, as a recent report from the Ohio River Valley Institute described reductions in income, jobs, and population across the biggest gas-producing counties in the region over the last ten years, compared to the national average.[6]

Fracking and Cracking

Because our region is so rich in gas resources, we are now preparing for a fleet of petrochemical facilities, such as ethane crackers, which heat up and “crack” ethane molecules to make ethylene, a commonly used component of plastic products (from antifreeze, to food packaging, to clothing). The first of these has been built in Beaver County, downriver and upwind of Pittsburgh, and it is expected to come online in 2022. There are many concerns about petrochemical expansion in the region because of potential health impacts seen around these types of plants elsewhere, specifically in Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley,” which is infamous for cancer risks 50 times higher than those experienced by the average American.[7]

At one point, the southwestern Pennsylvania / Ohio / West Virginia region expected to see as many as four or five cracker plants, but the pandemic slowed construction on the first and stalled planning for the others last year.[8] Nevertheless, growing demand for plastics will continue to support the case for more cracker plants, and cracker plants will need to be fed with gas, which will be fracked from across the region and transported via a pipeline that has already come under scrutiny for safety issues.[9]

Additionally, health and environmental concerns that come with both fracking and petrochemical development will grow alongside demand for plastics and the gas that serves as feedstock. And that was all I could think about this weekend as we got in the car to drive 45 minutes to one of our favorite restaurants, which is still only doing take-out orders. We sat at a picnic table outside the building, downhill from a recently fracked gas well, eating food out of Styrofoam clamshells. And so, although I do my best to avoid any topics related to my work on this blog, it could not have been more present in my mind as I came into this year’s Plastic Free July.

Mitigating Steps

I do plan to make my way through July this year much as I did last year: limiting my purchases of plastic and carrying my total accrued plastic waste for the month as a sign of shame. I’ve never made it through July without generating some plastic waste, but I have succeeded in significantly limiting it when I try. Given that, I knew we would be getting our food in single-use plastic containers on this trip, but I didn’t want to duck out of lunch with my in-laws or a trip to this restaurant, which has better Korean food than I ate in Seoul.

Therefore, we did what we could. We packed up a cooler of drinks (in glass bottles), condiments from our fridge (soy sauce and chili crisp), and reusable tableware (plates, chopsticks, and serving utensils). Christian was as patient as he could be when I made him remind the woman who took our order that we didn’t need plates, chopsticks, forks, or sauce packets. It was actually a lovely day, and packing up our own supplies beforehand made it feel like we were going on a picnic, rather than going to a restaurant.

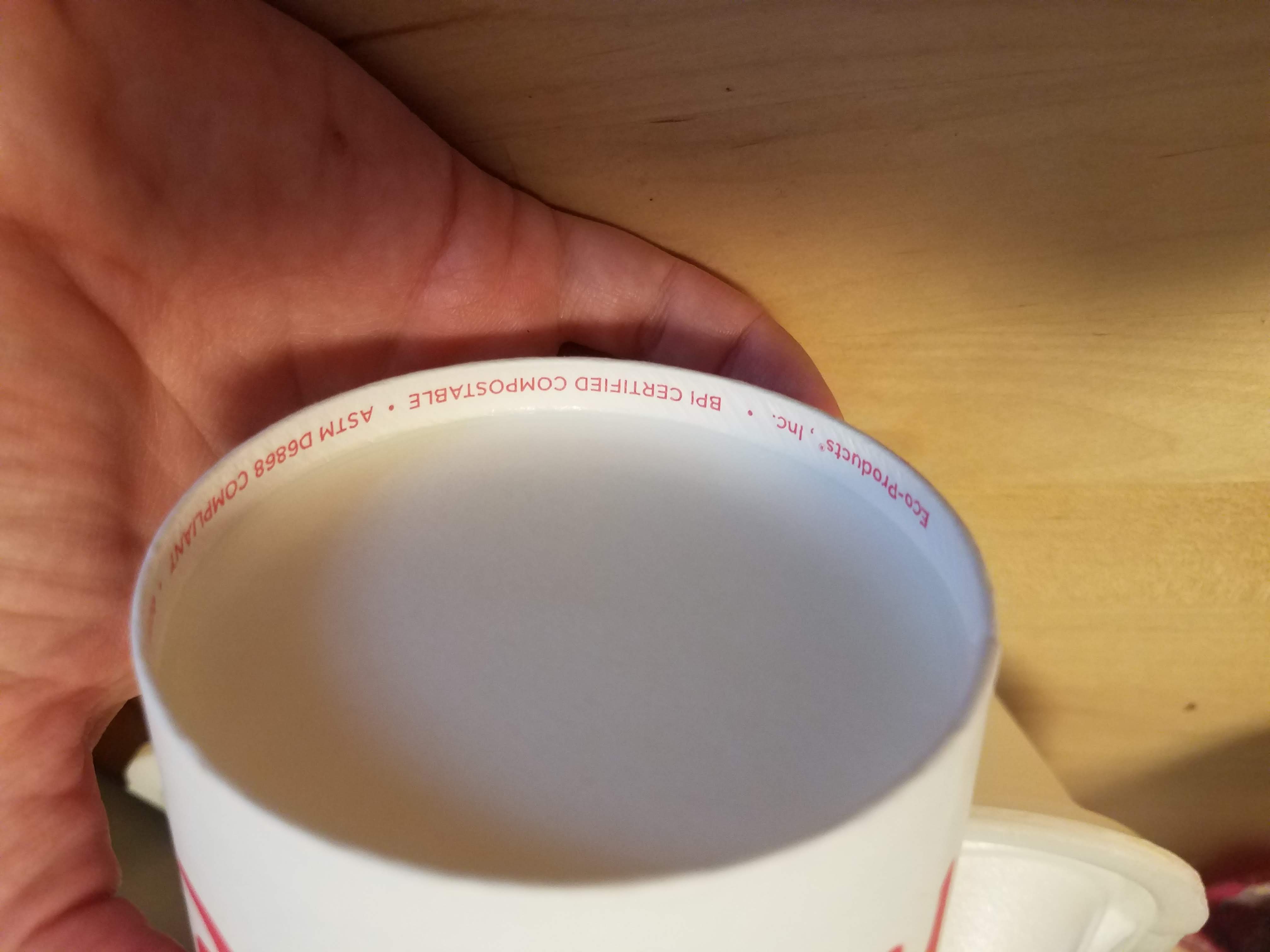

Although we were stuffed, we decided to stop for ice cream at a local chain on our way home. I wasn’t sure I was going to order anything – not because I couldn’t find room, but because single-use paper cups (the kind you would get for coffee or ice cream) typically have a thin layer of plastic to protect the paperboard from getting wet. That would have meant no ice cream (or far too much ice cream in a waffle cone) for me, but I noticed that their cups were certified compostable.[10] Compostable serviceware will break down in a commercial compost stream; not in your back yard bin. Throwing them in the garbage is just as bad as using standard cups because they will not break down in a landfill. Fortunately I know a guy who works at a composting company, so I enjoyed one scoop for dessert (with a spoon from home).

~

I recognize that I’ve already failed at zero waste this July, but through thoughtful steps I can reduce what I might have done to contribute to demand for plastic, the gas that will go to make it, and the subsequent (largely) unrecyclable waste after we use it. I’d love to hear about how you’re challenging yourself with Plastic-Free July.[11]

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://www.publicsource.org/have-environmentalists-lost-their-battle-to-thwart-the-petrochemical-industry-in-southwest-pa/

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july/

[3] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-corona-edition-part-1/

[4] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/surface-transmission.html

[5] https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/china-ban-plastic-trash-imports-shifts-waste-crisis-southeast-asia-malaysia

[6] https://ohiorivervalleyinstitute.org/new-report-natural-gas-county-economies-suffered-as-production-boomed/

[7] https://www.businessinsider.com/louisiana-cancer-alley-photos-oil-refineries-chemicals-pollution-2019-11

[8] https://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/2020/09/21/in-the-ohio-river-valley-with-the-pandemics-help-the-petrochemical-boom-is-on-hold/

[9] https://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/2021/03/17/dep-pointed-feds-to-whistleblower-complaints-about-shell-pipeline/

[10] https://www.compostingcouncil.org/page/CompostableProducts

[11] https://www.plasticfreejuly.org/

2 Comments

Will · July 7, 2021 at 12:13 pm

What is a “commercial compost stream” and how can I find one?

What is the best way to dispose of “certified composable” serviceware?

My known options are my backyard compost, curbside recycling, and the municipal yard waste facility.

Alison · July 13, 2021 at 10:07 am

Hi Will,

Commercially compostable items must go into a composter that is designed for higher heat to break down things like meat, bones, and serviceware – things that won’t break down in a backyard compost pile. Certified compostable serviceware can’t be recycled, and it won’t break down in a landfill – if it doesn’t go to a commercial composting facility, it behaves just like regular trash.

If you’re in the Pittsburgh area, I can make a couple recommendations, such as…

Pennsylvania Resources Council: https://prc.org/ (they might just do events – I’ve used them for work meetings and my wedding, but not home compost)

The Pittsburgh Garden Company: http://www.pittsburghgardencompany.com (they’re just getting started, and I’m not sure their service area, though I did use them for a party I hosted at my home)