Part 1

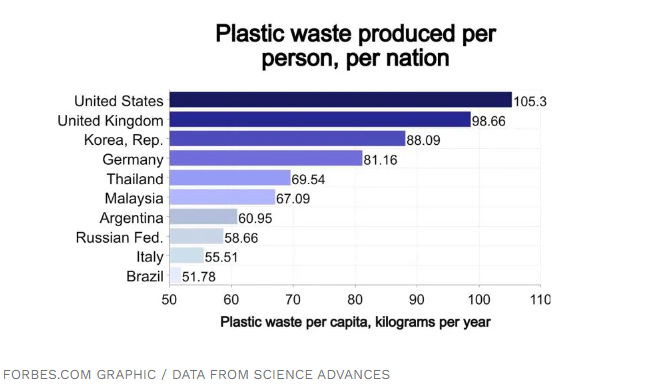

It is once again July, and for the last five years I have made a habit of committing to less plastic use through the “Plastic Free July” initiative. [1] This year has been a struggle for me and my family on a personal level, and I have barely had enough energy or motivation to be a functional adult, let alone a responsible one. With as much as I have preached from this online soapbox in years past about the importance of reducing plastic use in the first place, rather than relying on promises of plastic “recycling” programs to clean up our mess, I feel like a hypocrite whenever I don’t make a reasonable attempt to limit instances of plastic use in my life, but this ubiquitous product remains a pervasive problem.

My groceries from a local CSA arrive in single-use plastic; my biodegradable cat litter arrives in single-use plastic; my native plants and beneficial garden insects arrive in single-use plastic. I meticulously collect and sort the discarded packaging, recognizing that there are few alternatives at the moment if I still want to buy the same eco-friendly products and support the same local businesses. However, I am also aware that my plastic waste, smaller than average though it may be, will still meet with a less-than-ideal end, no matter where it goes.

Image credit: [2]

Tricky Terminology

Five years ago when I started this blog, my very first post was about recycling – specifically the difference between what was being collected and what was being recycled, because those two things are not the same, especially when it comes to single-stream curbside pickup, [3] which is why I no longer make use of our curbside program and just sort and drop off all of our recyclables myself. Since then, I have been consistently skeptical of “recycling” programs, particularly those that collect hard-to-recycle materials, such as #3 through #7 plastics. The term “recycling” is frequently mis-applied to what is happening, especially for plastics, as I explained in a 2021 post that described how my plastic waste was being downcycled (not recycled) to create a landscaping product called HydroBlox. [4] The overwhelming lack of accurate terminology is part of why it is now so hard for consumers to make informed choices.

I think it’s fair to say that most of the people I know personally want to do the “right” thing in any given situation. Unfortunately, it’s not always clear what the “right” thing is, and everything from lack of transparency to rampant misinformation contributes to confusion, frustration, and even the urge to give up altogether. I was going to use Christian as an example here, since I’ve changed our plastic sorting process at home enough times that I’m just now responsible for it in its entirety… but in all reality, I feel like I’m hitting my emotional limit as I learn more about the drawbacks of new systems being put in place for plastic waste management and have more difficulty, myself, discerning what the “right” thing is.

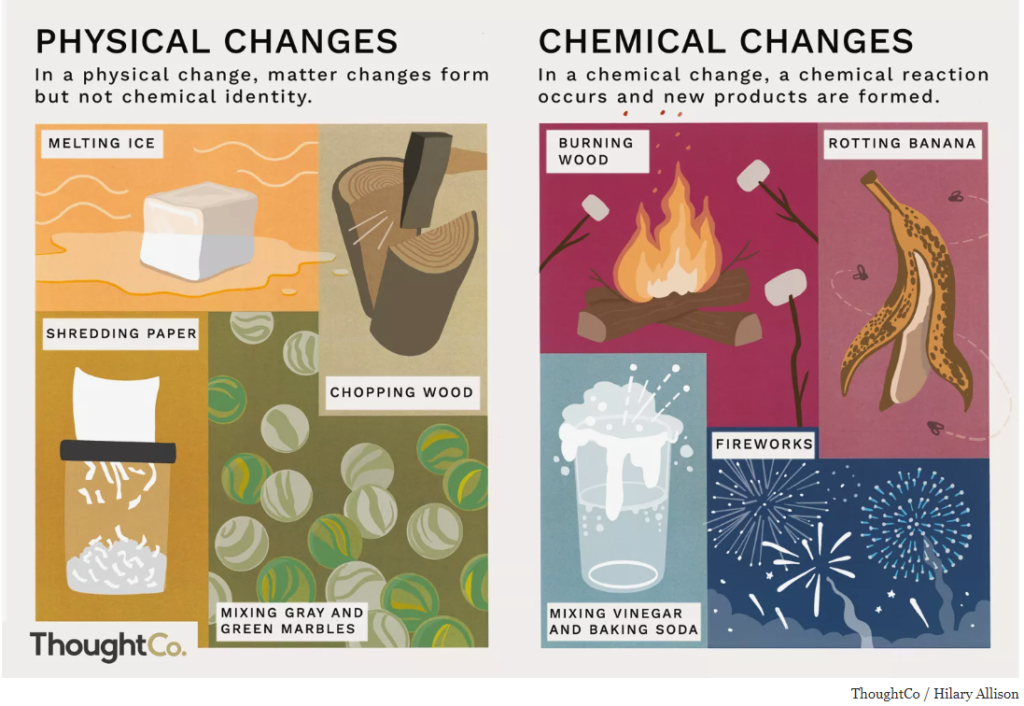

To get a better sense of the impacts of our decisions, it’s important to go back to elementary school science class. I can picture a page from my (I think) third grade science textbook, which had an image of an ice cube next to an image of a piece of wood: the ice undergoes a physical change when it melts; the wood, a chemical change when it burns. This difference is a central component to what might be happening with our plastic waste now vs. in the near future, which is why we need to become acquainted with terms such as “mechanical recycling” and “advanced recycling” (a.k.a. “chemical recycling” or “molecular recycling”).

Image credit: [5]

Mechanical Recycling

What we are meant to think of when it comes to plastic recycling is a plastic bottle going to a recycling facility and becoming another plastic bottle, as part of a 100% recycled, closed loop system. That lovely, responsible, eco-friendly mental image, encouraged by the plastics industry since at least the 1990s, actually happens very rarely in reality, with less than 10% of plastic actually getting recycled – with the remainder being landfilled, incinerated, or making its way into our waterways and oceans. Programs like single-stream curbside recycling and the ubiquitous “chasing arrows” symbol on all types of plastics (whether they are recyclable or not) have led consumers to believe that all plastic is, in fact, recyclable, which enables us to turn off our brains both when we shop and when we sort our garbage. [6]

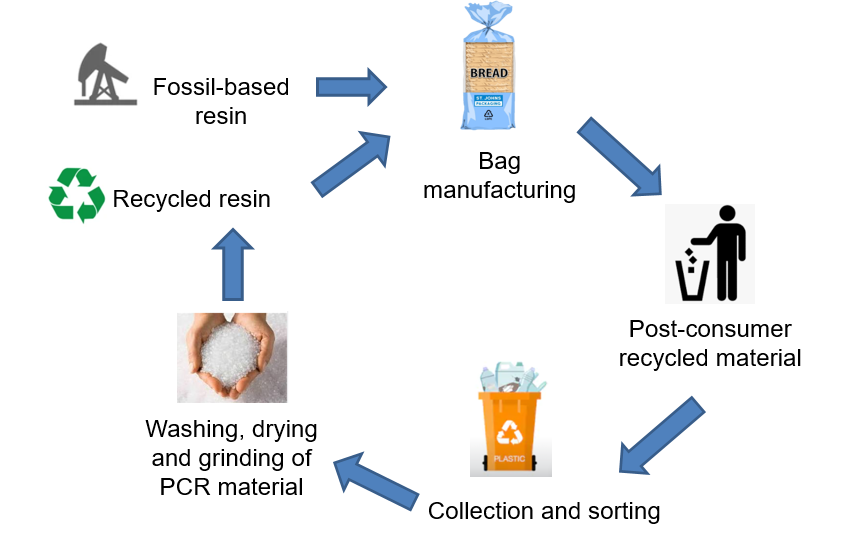

Part of the reason why so little plastic gets recycled in the first place is because so little of our consumer plastic is commercially recyclable. In the best case scenario, polyethylene terephthalate (PETE, #1) bottles, high-density polyethylene (HDPE, #2) bottles, and polypropylene (PP, #5) containers are collected, sorted, washed, dried, shredded into pellets, and then used again, each to make products of the same kind. However, plastics degrade over time and through the melting and reforming process; there is also frequent product contamination – largely from food waste that hasn’t been rinsed out of the containers – which limits how much of the recovered plastic can be recycled, even if it’s the right kind. [7] For these reasons, virgin plastic is added to the recycled plastic to help it retain the properties it needs, but realistically, plastic recycling is still expensive and ineffective after about two times through.

There are other mechanical processes for plastic waste recovery, such as in the HydorBlox example mentioned above, but downcycling plastic into a different product is notably not “recycling.” At the time I did the research for that post, Michael Brothers Hauling and Recycling (where I take my recyclables) [8] was selling plastics #2 through #7 to be melted down together to create the landscaping product. That is the end of the line for those materials, as they are melted together and can’t be separated back into their component plastics, but it was still being advertised as plastic recycling, which it is patently not. Nevertheless, I would see loads of conscientious citizens at Michael Brothers every weekend, unloading boxes of plastics from their cars, feeling like they were doing the right thing.

Image credit: [9]

Don’t get me wrong – I was there dropping off my plastics too, and I even said at the time that it seemed better to reuse the plastics for something than to send them to the landfill. But I also knew that our plastic wasn’t actually getting recycled, which is why I was making an effort to buy less of it in the first place – and that is still my goal. And it should be the goal for anyone who is concerned about plastic waste, no matter what we hear about seemingly “too good to be true” solutions coming down the pike… which is where we’ll pick up next week, with the concerningly named process of “advanced recycling.”

~

Until then, I would love to hear if you’ve pledged to participate in Plastic Free July. [10] Let me know how you’re working to limit your impact.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/tag/plastic-free/

[3] https://radicalmoderate.online/new-recycling-guidelines-in-the-south-hills/

[4] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-waste-options-in-pittsburgh/

[5] https://www.thoughtco.com/physical-and-chemical-changes-examples-608338

[7] https://www.breadbags.org/mechanical-vs-chemical-vs-advanced-recycling-what-are-the-differences/

[8] https://michaelbrothershauling.com/

[9] https://www.breadbags.org/mechanical-vs-chemical-vs-advanced-recycling-what-are-the-differences/

[10] https://www.plasticfreejuly.org/

1 Comment

rjwarren59c8cb9109c0 · July 7, 2024 at 3:57 pm

I must work harder to say no to plastic. Thank you for your work, wisdom and love of our planet.❤️❤️

A.B.