Part 1 – The Recycling Myth

Disclaimer: I will be talking about work in this series and need to reiterate that the content of this blog represents my personal position and/or positions of the organizations referenced; it does not represent the position of any organizations I am involved with.

Once again, the beginning of July has caught me off guard. I am shocked and saddened that the year is already half over, and the days are getting incrementally shorter. I feel like I’ve barely gotten started on my garden plan for the year and haven’t taken any time to enjoy time in nature (says the woman who spends 10-plus hours gardening every week and blogs from her porch on Sunday mornings). But July means more to me than just the halfway point of the calendar year: it is the month that many people across the globe reserve to pay extra attention to our consumption and handling of plastics.[1]

As I mentioned in last year’s Plastic-Free July post [2] and frequently in recent mental health content,[3] I try very hard to keep my work and personal lives separate in order to, among other things, avoid burnout. And I recognize the immense privilege I have to be able to say that – many frontline community members I work with on a regular basis do not have the ability to “step away” or “take a break” because facilities concerning them (e.g. wellpads, pipelines, compressor stations, etc.) are in their neighborhoods.

But that separation becomes an increasingly difficult task over time, as work-related issues encroach into my personal life more frequently, and it feels like only a matter of time before we’ll all be members of a frontline community. The ethylene cracker in Beaver County, PA, which residents have been fighting for years, and which I referenced in last year’s Plastic-Free July post, starts up – ironically – this month, and it will use fracked gas from the region to make… plastics.

Perception of Plastics

The plastics supply chain, from start to finish, represents devastating (and I do not use that word lightly) social and environmental impacts. Plastics are generally made from oil and gas, fossil fuels that have long represented the backbone of our energy and transportation sectors. As we see an increased global push for a transition to renewable energies in order to stem average global temperature rises, oil and gas interests have been scrambling to offset shrinking demand… and plastic represents the next outlet for their product.

I recently attended a conference that focused on environmental, climate, and health impacts from the extraction and use of oil and gas, and much of the content was focused on plastics, including a one-day dedicated workshop on the petrochemical industry, of which plastics play a major part. Part of the problem is that if you don’t live next to an oil or gas extraction operation, a petrochemical plant or refinery, or in a developing country that has accepted mountains of plastic waste from the United States, you may be largely unaware of the scale of the problem.

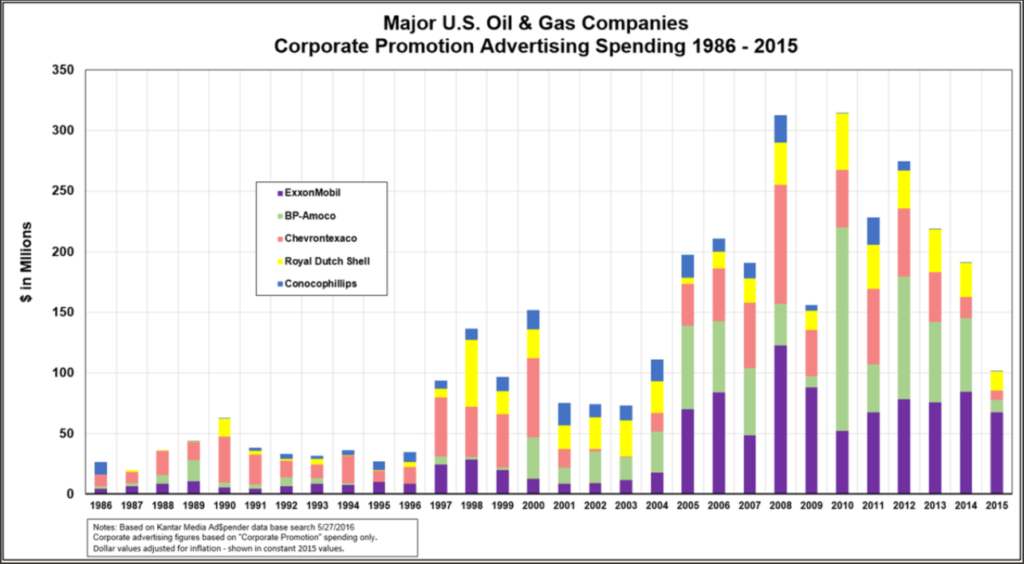

Big players in the oil and gas industry have tried to keep it that way, spending close to $4 Billion (with a B) on public relations over the last three decades to improve public perception about their activities, making sure that the problem doesn’t seem as big as it is, or making sure that they are seen as being part of the solution.[5] More recently, particularly over the last two years during the COVID-19 pandemic, the narrative has shifted to make plastics seem vital from a healthcare standpoint (think single-use medical supplies in hospitals) and from a public health standpoint (think single-use service supplies in restaurants).

One of the issues brought up at this conference – and I hope to cover it in more detail in the future – was that while plastic is necessary in some applications (including some medical supplies), production of those products represents a tiny percentage of the plastic products we actually create on a global scale. Additionally, I have been told by those more aware of this issue than I am that the amount of plastics used during the pandemic barely put a dent in our global supply of feedstock, meaning there is more of a perception of need than an actual need.

When it comes to public perception, this whole subject is fraught with oversimplifications of complex issues (at best) or downright misinformation and greenwashing – and it has been for decades. Slick marketing messaging has been used to dilute public awareness of problems and shift the focus from corporate actions to individual actions, or what we can do to fix the problem. And while I plan to cover a number of topics and stakeholders during this series, we will start with the most insidious one that laid the groundwork for plastic’s prevalence over the years: recycling.

Recycling or “Recycling”?

Several years ago PBS’s Frontline revealed that recycling was heavily promoted by the plastics industry to support increased use of plastic by consumers, despite clear indications that the industry knew recycling would not be economically viable. In the mind of the public, it is easy to choose plastic packaging if it can be recycled and effectively eliminate one’s waste footprint.[7] Most of it, however, does not – and cannot – get recycled, even when that’s what the process is called.

I’ve covered the subject of plastic “recycling” before, specifically regarding a privately owned waste and recycling business near us, which is – full disclosure – where I take our plastic waste. They accept plastics #1-7, a wider range than what is accepted in most curbside programs. When I asked what happens to the higher-number plastics, which are generally not recycled anywhere, they explained that they have a contract with a company that works in collaboration with Dow Chemical to create a landscaping product for water drainage. To create the product, all commingled plastics provided are melted down together and extruded into something resembling plastic funnel cake.

This process is referred to as “recycling” by the company near us that collects the plastic [8] and by the company that makes the landscaping product,[9] but what they are doing is not “recycling” that plastic. I freely admit that I will get on any soapbox at any time about semantics, but the reason I raise this point here is because terminology has been the crux of the plastic industry’s strategy for decades. Recycling is a closed-loop system that takes one material and makes it usable again as that material, specifically retaining or reacquiring “the properties it had in its original state.”[10]

When it comes to actual plastic recycling, it is incredibly cost-ineffective, which is why so little is recycled. For example, there are slight chemical differences among different products categorized as #1 plastics, which is why not all #1 plastics are recycled. That is why a mix of “hard to recycle” plastics, notably #3-7, is not getting “recycled” by anyone. This plastic funnel cake represents the end of the line for these materials – like actual funnel cake, you can’t later separate it into its component ingredients. That’s not to say this product is inherently bad. Using a plastic waste stream instead of virgin plastic to make this product is a step in the right direction, but it is the last in a long line of options that start with simply reducing our plastic consumption in the first place, and it should not be mislabeled as “recycling.”

The reason I am particular about this term can be summed up best by a quote from Larry Thomas, the former head of the lobbying group Society of the Plastics Industry (SPI): “If the public thinks the recycling is working, then they’re not going to be as concerned about the environment.”[12] And I have to admit that, even knowing what I know about the supply chain, having a downcycling outlet for our plastic waste has made me a little less vigilant about what comes into the house and what I myself consume.

Recycling (or even downcycling) is perceived as a “get out of jail free” card for our society, when less than 10% of our plastic actually gets recycled. But it’s important to know that even if 100% of our plastic could get recycled, that wouldn’t eliminate the health or environmental risks associated with the process. Next time we’ll continue with something else grouped into the “plastic recycling” category and the specific impacts associated with that process.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://www.plasticfreejuly.org/

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-corona-edition-continued/

[3] https://radicalmoderate.online/this-is-fine/

[5] https://grist.org/energy/big-oil-spent-3-6-billion-on-climate-ads-and-its-working/

[6] https://grist.org/energy/big-oil-spent-3-6-billion-on-climate-ads-and-its-working/

[8] https://www.redefiningtrash.com/post/new-plastics-recycling-opportunity

[10] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0921344902000563?via%3Dihub

[11] https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/trust/archive/fall-2020/confronting-ocean-plastic-pollution

0 Comments