As I mentioned in last week’s post, [1] I recently bought another carload of plants from my favorite native plant nursery. [2] It is absolutely fall planting season for the time being, but I was (unsurprisingly) overly ambitious with what I thought I could get in the ground in a short few weeks and came home with four flats of perennials and a shrub – not all of which will be planted before we leave town on vacation. Fortunately some of the garden beds I’m trying to fill are a couple years old at this point (making them easier to plant than the clay-heavy newer ones I’ve just started converting), and I also adopted a new tool this year that is making the planting process significantly easier.

In last week’s post, I talked about garden planning and my own analysis paralysis. But here’s the thing: all the planning in the world won’t necessarily do you any good if you get to the nursery and can’t find what you had intended to plant – or if you find something interesting that wasn’t in your plan. And that aspect of plant shopping can be exciting if you’re flexible (or frustrating if you’re not). The first time I went to the nursery with my commissioned plan, complete with exact plant types and quantities, I wasn’t sure what to do when certain things weren’t available yet, and I was hesitant to substitute with a similar option. A little over one year later, and I’m at the point where I’m just grabbing anything that catches my eye, knowing I can tuck it in somewhere. (Multiple sets of threes of the same kind of plant are a great way to create some visual continuity.)

Staying Open to Options

My excitement has grown in the past couple years, as I go to the nursery when it opens, curious to see what’s available. And because it’s a native plant nursery, I can feel confident that anything I buy will support native pollinators – I don’t have to worry too much about what I’m buying – just that it will be something that likes sun and tolerates drought. This year, however, I was faced with a small conundrum (really more of a manufactured conundrum than a real one, if I’m being honest). When visiting my aunt’s garden center back home [3] and the native nursery near me, I had the option of buying what are called cultivars. And that, I have found, can be a huge point of contention online among native gardeners.

Yes, if you can believe it, there are people on the internet with strong opinions! One of the first things I did when I started researching native pollinator gardens a few years ago was to join a Facebook group for native gardeners in Pennsylvania. There was an incredibly firm stance (either official at the group level or just held by an exceptionally vocal supermajority of members) against cultivars. Cultivars are a species subgroup, or variety, that is often deliberately cultivated: hence the name culti-var. Some are the result of genetic mutations and are simply found in the wild (“sports”). More frequently, they are hybrids of different plants, bred intentionally to have certain characteristics, such as disease resistance or longer bloom times. [4]

Image credit: [5]

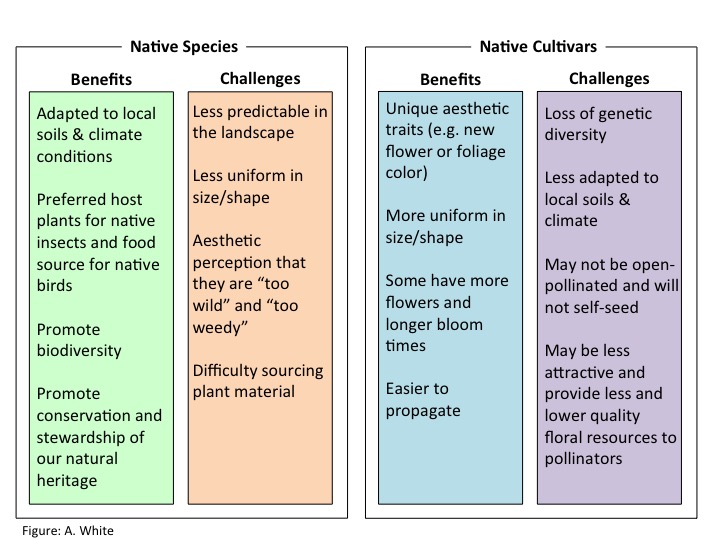

The arguments against cultivars include that because they have been bred to have certain characteristics, others natural features (such as pollen or nectar production) might suffer, to the detriment of pollinators. Many cultivars are sterile, meaning they cannot reproduce on their own and must be propagated through cloning or grafting, which limits options for genetic diversity within the variety, harming overall biodiversity. Many of the native gardeners I encountered online were adamant that cultivars of native plants (or “nativars”) were therefore unacceptable and incapable of supporting native pollinators as effectively as the original straight species. [6]

Cultivars and Nativars

Interestingly, though, my two favorite nurseries now carry nativars, which got me thinking. Sure, they’re businesses and need to cater to their clientele, but they’re also run by very responsible women who do their research. While I was originally hesitant to consider buying anything that wasn’t a straight species (and indeed felt guilty about any nativars I had previously added to my garden) because of the vehement opposition to them on Facebook, I now recognize that there may be other factors to consider than just ecological benefit. (That is, of course, my top priority, but not necessarily everyone’s – so the assumption that everyone should have the same priorities feels a little myopic.)

For example, some nativars are smaller or have a neater growing habit, which may be a factor for someone who has a very small garden area to plant or is trying to plant natives in a Homeowners Association (HOA) situation that has unrealistic rules about what the garden should look like. [7] Additionally, not everyone has access to a native plant nursery within an hour’s drive like I do, and planting nativars that are available in more mainstream stores could still be preferable to invasive species. If we think of it more as a spectrum of options rather than clear categories of right and wrong, that might open up more windows of opportunity for us to learn from each other. (Just a thought.)

And just because a nativar might be less attractive to pollinators than its straight species equivalent, that doesn’t mean it is not attractive at all. [8] And as I’ve done more research, it has been interesting to learn that not all cultivars are created equal, and that the closer they are to the straight species, the more attractive they are to pollinators; the more manipulated they are, the less attractive. [9] What that means is that if you can find seed-grown or naturally occurring cultivars, those are probably your best bet. I tend to be a little more skeptical of tags that talk about patents and how propagation is prohibited.

So with that inhibition slightly eased, I grabbed a couple nativars when I was shopping, and added them to my exceedingly long planting list for this fall. Fortunately, I was able to try out a new tool that helped me work smarter, not harder, and make a lot more progress than I anticipated. More on that next week.

~

Where do you fall on the issue? Have you had success with cultivars or nativars in your yard? I’d love to hear about it in the comments below.

Thanks for reading!

Keep reading about this year’s garden updates –>

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/planning-a-pollinator-garden

[2] https://arcadianatives.com/

[3] https://www.facebook.com/pharogardencentre

[4] https://piedmontmastergardeners.org/article/a-gardeners-guide-to-plant-nomenclature-part-ii/

[5] https://pollinatorgardens.org/2013/02/08/my-research/

[6] https://grownative.org/learn/natives-cultivars-and-nativars/

[7] https://radicalmoderate.online/for-the-birds/

[9] https://pollinatorgardens.org/2013/02/08/my-research/

0 Comments