I have previously referenced Michael Pollan’s treatise on the concept of the American lawn and our emotional connection to this thing that simultaneously represents democratization and individual status.[1] As I was trying to reduce the size of our lawn this year by expanding the gardens, the contrast between our yard and our neighbors’ was all the more stark. Some (but not a lot of) homes in our neighborhood regularly have green lawn companies pull up in front of their houses to spray down their yards. Some still run sprinklers, which always surprises me to see.

Neither my husband nor I really buys into the hype of the perfectly manicured front lawn, as should be obvious by one look at our yard. He used to put down chemical fertilizer two or three times a year as a matter of course, until I dissuaded him, asking him instead to use an organic fertilizer. He agreed on the condition that I select and buy it. It was an easy deal to make, but since that conversation, we’ve really fallen off the lawn care bandwagon altogether.

We are most certainly in the minority here. Lawns are the most irrigated “crop” in America (more than corn!), and their upkeep requires 17 million gallons of gas for lawnmowers and tens of millions of pounds of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, all to the tune of $36 billion (with a B) per year.[2] However, if you’re lazy like us, and you’re only going to expend effort on your lawn once a year, fall is the time to do it. And below is the best advice I have been able to find regarding organic lawn care.

Before I go any further, I want to define the terms I’m using here – mostly because I don’t want to hear any “but organic compounds are chemicals too!” retorts. When I use the term “chemical fertilizer,” it refers to inorganic material that is in part or entirely derived from synthetic origin. “Organic fertilizer” refers to organic materials (or their remains).[3]

Chemical (Inorganic) Fertilizers

These fertilizers are refined in a process that extracts nutrients and binds them with chemical fillers. The nutrients are concentrated, making them very powerful.

Pros:

- Nutrients are available to plants immediately

- Chemical ratios are highly standardized

- They’re cheaper to buy because you need less volume

Cons:

- Production is more fossil-fuel intensive than that of organic fertilizers

- They give plants the nutrients they need, but do not sustain soil health by replacing trace elements that are slowly used by the plants

- Overuse can burn plants and/or upset the soil ecosystem

- They can leach into wells or local waterways, upsetting aquatic ecosystems and requiring more applications to replace what was carried away through runoff

- Repeated use over time can change soil pH, upset the soil ecosystem, and lead to a buildup of toxic chemicals in the soil [4]

Organic Fertilizers

These fertilizers are often remnants of organic materials, usually plant or animal waste. They are minimally processed and do not involve extraction of nutrients into a concentrated form.

Pros:

- They don’t only feed the grass/plants, but condition the soil, enabling it to hold more water and nutrients and promote plant/grass health

- You can’t really over-fertilize with them, since they are inherently slow-release

- Since there are few or no additives or binders, there’s a smaller risk of chemical buildup in the soil

- They are the ultimate reuse/recycle option, making them more environmentally friendly from a production standpoint

- You can make your own for free

Cons:

- They are slower to release their nutrients into the soil

- Nutrient ratios aren’t standardized

- More volume of product is required since the nutrients aren’t concentrated, which can be more expensive [5]

Image credit: [6]

Milorganite

I rarely mention specific brand-name products or companies on this blog, but I do make exceptions for unique products that have notable benefits. For several years now, I have purchased Milorganite for our lawn, based on the advice of my aunt who owns an organic garden center.[7] Christian accuses me of choosing it simply because it’s fun to say the name, but there are other positive attributes as well. He refers to it simply as “hippie shit,” which he amusingly did before learning about the common misconception of how it is made.

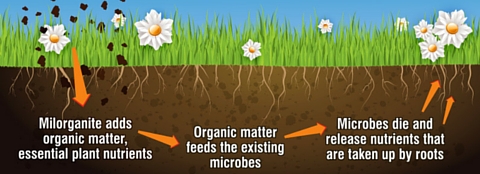

Milorganite is an organic nitrogen source, made from microbes that have lived their life in a wastewater treatment facility in Milwaukee (hence the “Mil” in the name). During their lifecycle, these microbes absorb nutrients from solids in the wastewater. After they die, binding agents are added to the tank, and the microbes clump together. They are then removed from the tank, pressed to remove excess moisture, and dried in a rotating kiln. The heat in the kiln kills any pathogens that might remain. As a sustainability bonus, that kiln is powered with methane captured from a local landfill.[8]

As an organic fertilizer, there is no risk of over-application (which isn’t a risk in our yard anyway, but I digress). It has a slow release over 10 to 12 weeks, and the phosphorus will not leach into wells and waterways. According to their website, Milorganite is safe for kids, pets, and wildlife, though I have noticed that the smell, while subtle, keeps the deer out of our yard for a few weeks or until a heavy rain.

Since this organic option works to provide nutrients to the grass and build out the health of the soil, you will see the benefits over time, not immediately. However, those benefits will be longer-lasting, and your lawn will be healthier and more resilient in the face of pests, drought, and weeds. Milorganite recommends four applications for year, but if you’re only going to do one, it should be as late in the season as possible, before the first deep freeze or snowfall. As much as I hate to say it, it’s about that time.

Image credit: [9]

The Ultimate Status Symbol?

Applying fertilizer to the lawn is incredibly easy if you have a broadcast spreader, which we already did, though ours is branded with a massive logo of a product we no longer use. Just be aware that you will need to use a different setting for organic fertilizers, since they pack less punch per volume than chemical fertilizers.

As I mentioned before, our yard will never show up in an advertisement for organic fertilizers because a lush, manicured lawn is so incredibly low on our priority list. We’ve probably succeeded in two applications of Milorganite over the last three years, instead of the recommended 12 during that time. We’ve actually spent more effort spreading clover seeds than fertilizer, in an attempt to replace our grass with a lower-maintenance option that is more pollinator-friendly and absorbs more nitrogen. But that is a topic for another post.

If you are a fan of the perfect lawn, the best way to sustain it is through building up the health of your soil. Healthier soil leads to stronger, deeper roots, which means less need for watering. Thicker, healthier grass is more capable of choking out weeds, reducing the need for weed killers that can also harm beneficial insects (and potentially kids and pets). Proactive maintenance to support a naturally healthy lawn will reduce the need for expensive chemicals that only give the appearance of a healthy lawn.[10]

~

How do you feel about lawn care? If you are devoted to the perfect lawn, what are your tried-and-true methods? I’d love to hear more about your experiences below.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://michaelpollan.com/articles-archive/why-mow-the-case-against-lawns/

[2] https://grist.org/article/lawns-are-the-no-1-agricultural-crop-in-america-they-need-to-die/

[3] https://www.diffen.com/difference/Chemical_Fertilizer_vs_Organic_Fertilizer

[4] https://www.todayshomeowner.com/debate-over-organic-chemical-fertilizers/

[5] https://www.todayshomeowner.com/debate-over-organic-chemical-fertilizers/

[6] https://www.milorganite.com/using-milorganite/what-is-milorganite

[7] https://www.pharogardencentre.com/

[8] https://www.milorganite.com/using-milorganite/what-is-milorganite

[9] https://www.milorganite.com/using-milorganite/what-is-milorganite

[10] https://www.thisoldhouse.com/lawns/21015220/tips-for-a-lush-organic-lawn

0 Comments