When I first envisioned my organic garden, it somehow managed to be a beautiful oasis with minimal (not ongoing) work to keep away weeds and pests. In hindsight, that’s a pretty cute trick for someone who wasn’t going to be using any herbicides or pesticides. As it happens in real life, I’ve been spending most of my available time this spring dealing with more unwanted flora and fauna than I anticipated.

It is frustrating and tiring, and I have reached the point where I can understand (not agree with, but understand) why some people want a simple solution in the form of a spray to take care of these issues. However, simple sprays (or all-in-one lawn services) can create other problems down the road, which is why I am remaining committed to a natural approach to weed and pest control. That commitment has meant additional research and leg work for me as I deal with a very common unwelcome guest: the aphid.

Aphididae

There are about 5,000 types of aphids in the superfamily Aphididae, and I think I have seen most of them in my garden this year. What they have in common is that they are small, soft-bodied, sap-sucking insects that can do serious damage to plants by weakening them and even spreading disease. Populations can multiply quickly, as females do not need males to reproduce and can give birth to live nymphs (not eggs), which may also already be pregnant with clones of themselves.[1]

Some friends and I have commented on the fact that we’ve seen more aphids than usual this year. While I’m used to seeing a few, some of my plants started positively exploding with them this spring, particularly the foxgloves in my front garden and several flowering weeds behind the house. It’s possible that more eggs survived this past winter because of the milder weather we had, but I was also curious as to why they seemed to be congregating on certain plants.

I more recently learned that an aphid infestation on a particular plant or area can be an indication of over-fertilization.[2] This conclusion is based on the fact that aphids love nitrogen. Nitrogen is a major factor in plant growth, so aphids are particularly attracted to seedlings (which grow quickly and therefore use a lot of nitrogen) and potentially plants that are getting a lot of nitrogen through compost, fertilizer, or particularly nitrogen-rich soil.

High nitrogen levels contribute to fast plant growth and thin cell walls, which are easy for the aphid’s mouth to pierce. Having a proper balance of magnesium, phosphorus, and carbon in the soil can help the plant form sugars. Interestingly enough, even though aphids feed on sap, higher sugar levels in the plant will be harmful to them. (They typically excrete extra sugar that their bodies can’t process in the form of a sticky substance called honeydew.)

An Ounce of Prevention

Given this piece of information, there are things you can do to prevent aphids from attacking your plants. The big two are these: 1) Don’t use fertilizers, but particularly not commercial/synthetic fertilizers, as they are loaded with nitrogen. 2) Get a soil test [3] to make sure that you have a healthy balance of soil components.[4]

It will also help if you remove any places in your garden where aphid eggs can over-winter. That means cleaning dead plants and brush out of your yard in the fall. (This advice is counter to my own guidance that I have provided on this blog before,[5] as other insects – including beneficial ones – benefit from leaves and dead plants staying in place until spring.)

A Pound of Cure

There are several things you can do to get rid of aphids once you have them, though it means more work and vigilance:

- Rub them off with your fingers

- Blast them off with water

- Spray them with a mixture of 3-4 Tbs pure liquid soap to 1/2 gallon water

(Be cautious when using this because it can harm beneficial insects too.) - Spray them with a mixture of 2 Tbs neem oil to 1 gallon water

(Same goes for this one – make sure you know what you’re spraying before you start.) - Release beneficial insects into the garden (more on these below!)

- Plant pest-deterring plants to keep them away altogether or pest-attracting plants to keep them in one spot

- Grow strong & healthy plants that will be less likely to fall sick when under attack

- Attract aphid-loving birds, such as chickadees, wrens, & titmice – buy feed, feeders, and houses for them

- Understand that you need some pests in your garden because they attract beneficial insects too – if nothing is eating your garden, it’s not part of the ecosystem.[6]

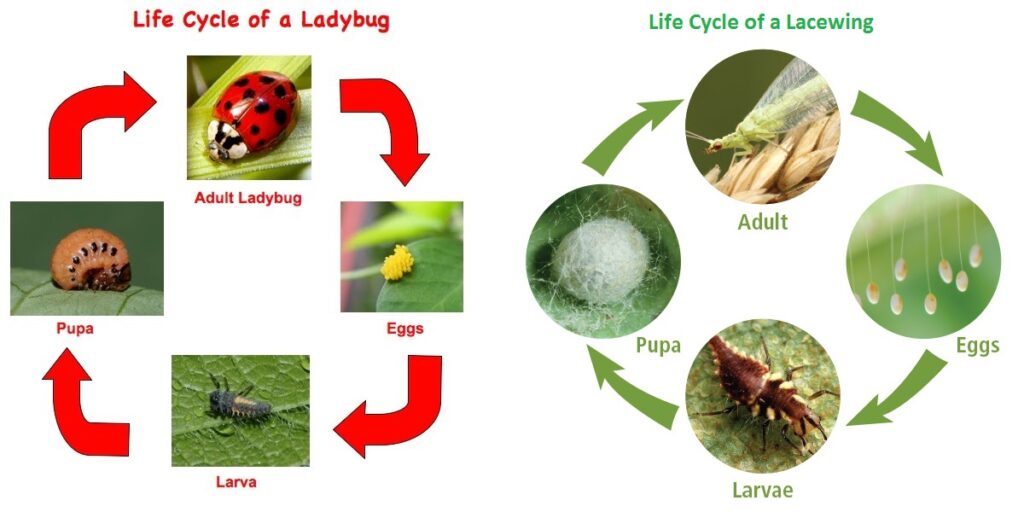

Image credits: Ladybugs [7], Lacewings [8]

Ladybugs (Lady Beetles)

The most commonly known aphid predator is the ladybug (actually a beetle).[9] While most people know what the standard ladybug / lady beetle looks like as an adult, I recently learned that most people do not know what they look like in earlier stages of their life. As so often happens on my neighborhood message board, someone asked a question that could have been answered with harmful or inaccurate information. (One example that comes to mind is last year when someone was telling anyone who would listen that red-dyed nectar was safe for hummingbirds – it’s not.[10])

In this instance, someone said he kept seeing a lot of ladybugs and some other types of bugs with them. He said he kept hosing them off the side of his house, but they kept coming back. Those “other” bugs, I informed him, were also ladybugs. They go through four stages of life: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Once they have hatched from their eggs, they will eat aphids and other sap-sucking bugs in all three stages of life, though larvae eat the most.

Eggs hatch in three to seven days; a larva will eat for two to four weeks before transforming into a pupa. Within five to seven days, the pupa will transform into an adult, which will live for a few months. It is important to remember what these stages look like because it is easy to mistake larvae and pupae for other, less friendly, non-beneficial insects and try to get rid of them, as my neighbor did.

Lacewings

Green lacewings [11] are the other aphid fighting force – generally less-known but more prolific in their consumption. Adult green lacewings do not eat aphids, but their larvae do, and they can eat up to five times as much as lady beetles. The adults are beautiful, but again, they may look less like an expected garden bug, meaning that they might be at higher risk of falling victim to an enthusiastic, pesticide-wielding gardener.

Female lacewings will identify a plant that has a large number of aphids nearby to provide a good food source for their children. They will lay eggs not directly on a leaf, but suspended by a strand of silk to hide them from predators. Ants in particular, which love to snack on aphids’ honeydew and therefore attack any potential aphid enemies,[12] would eat lacewing eggs upon encountering them. However, the strand of silk is small enough to escape their notice and keep the eggs safely hidden.

In about three to five days, the eggs hatch and larvae emerge. They will then consume up to 1,000 aphids a day for about 12 days before spinning a cocoon. After about 10 days in the cocoon, the lacewing will emerge as an adult. Adults will then mate and lay more eggs. The cycle is fast enough that you can get many generations of lacewings in one growing season.[13]

You can buy both of these beneficial bugs online. Since I already have a lot of ladybugs, I opted for the green lacewings. Typically you will see eggs packaged in rice hulls, which will allow them some protection in transit and from each other as they hatch. You can distribute them in paper cups throughout your garden or (as I have also seen done at organic garden centers) just sprinkle them at the base of any plants in question. It is recommended that you release three different sets one to two weeks apart. (That does not mean buying all three at once – you will need to space out your orders, as they are timed to be hatching right around the delivery date.)

~

Remember that the goal of organic gardening is to achieve a balance. If your plants are attracting a lot of pests, there may be an underlying cause to address before looking simply to eradicate them. And if you do eliminate all of the pests, there are things higher up the food chain (such as birds and beneficial insects) that will have less to eat.

That being said, I’d love to hear about any aphid control tricks that have worked for you.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aphid

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sGlqnkE1Id0

[3] https://agsci.psu.edu/aasl/soil-testing

[4] https://underwoodgardens.com/controlling-aphids-naturally/

[5] https://radicalmoderate.online/spring-garden-cleanup/

[6] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IMNesufL0_k

[7] https://sites.google.com/site/loveableladybugs/home/life-cycle

[8] https://www.arbico-organics.com/product/green-lacewing-eggs-on-cards/free-shipping

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coccinellidae

[10] https://radicalmoderate.online/hummingbird-101/

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chrysopidae

[12] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hNzeshvjZdw

[13] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EOwk3PRTmEw

0 Comments