Part 4 – The Cleanup

Completely unplanned, this post is going live one day after the 41st anniversary of the Three Mile Island reactor meltdown right here in Pennsylvania. It is ironically the disaster about which I know the least, even though I have driven past it many times over the course of my life. When the plant was shut down last fall, I was surprised to learn that many people did not know that although Reactor Two melted down, Reactor One remained operational.

Speaking of combating popular misconceptions, I have spent a lot of time on my soap box over the past several years telling people how safe it is to visit Fukushima. Indeed, you will absorb more radiation on the flight to Tokyo than you will on the ground in the exclusion zone. Much of the fear about current conditions there stems from the fact that there are still areas where evacuees are not allowed back, and tourists are not even allowed out of their cars as they drive along the highway.

These areas currently closed off to the public are commonly referred to as the “No-Go Zone,” conjuring images of Chernobyl, where 34 years later, you can get a radiation dose similar to a CT scan of your chest by standing on the site for about one hour. (Incidentally, the equivalent time in the Fukushima “No-Go Zone,” based on the measurements I took while we were there, would be about 3 months.)

The area in question is actually officially called the “Difficult to Return Zone,” and our tour guides at Japan Wonder Travel[1] issued us personal dosimeters for use during the tour to measure our present and total exposure. As a point of reference, the baseline radiation we saw in Tokyo before and after the tour was approximately 0.1 μSv/hr. As I mentioned last week, radioactivity is naturally-occurring across the world, and many major cities have higher background radiation levels than Tokyo.[2]

The highest level I saw on my device during the trip was just under 2 μSv/hr as we drove through (and did not get out at) the town of Okuma. The total exposure we experienced over the approximately 30 hours in coastal Fukushima prefecture was about 10 μSv, or about one percent of what we absorbed on our flight to Japan.

Radiation Exposure vs. Contamination

So why this continued image of danger? Why aren’t people allowed back yet? If it’s safe to drive through, why isn’t it safe to walk around? The answers to those questions come down to the distinction between radiation exposure and contamination.

Radiation exposure is what happens when you get an x-ray or fly in a plane: your body is exposed to energy emitted by a radioactive source. Radiation contamination is what happens when you touch, or breathe, or eat radioactive material: your body actually comes into contact with it. [3] The reason why there is still a “No-Go Zone” is because there are places where there is still a risk – not of exposure, but of contamination.

The areas around the plant experienced contamination because burning fuel created radioactive smoke. That smoke traveled by wind and settled on buildings and fields throughout the area as it cooled, making everything radioactive. The issue of safety in these towns is not because of what is currently happening at the plant, but rather what escaped the plant in 2011 and landed nearby.

Radioactive material emits several types of radiation: alpha, beta, and gamma. (There is a fourth, neutron, which isn’t an issue outside the reactor itself.) Alpha particles are made up of a proton and a neutron, and while they are very powerful, they don’t travel far – in fact, your skin can block them. Beta particles are high-energy electrons and can be blocked by aluminum or wood. Exposure to beta radiation can cause burns on the skin, like sunburn. Gamma radiation comes from high-energy photons (like light, but much more powerful) and causes damage to cells and genetic material. Unless you are encased in lead and/or thick layers of concrete, you are constantly being exposed to low levels of naturally-occurring gamma radiation.[4]

You will get the same amount of cell damage from gamma radiation in the exclusion zone if you’re driving down Route 6 or playing in the dirt. The safety precautions in effect in the “Difficult to Return Zone” are because of the potential for damage from alpha and beta particles. While your car can block beta and your skin can block alpha, you are susceptible to the effects of both if you inhale dust or ingest dirt that has bonded with radioactive material. Those particles can bombard your lungs, digestive tract, and glands, causing tissue damage and cancer if you get enough. The danger here is not the exposure, but the potential for physical contact, for contamination. Because of that risk, tourists are not allowed in, and residents are not allowed back until each town has been sufficiently cleaned up and declared safe.

The Cleanup Process

In October 2011, the Japanese government unveiled a decontamination plan that included cleanup for all areas with radiation levels above 1 mSv/year.[5] (For the sake of comparison, that’s equal to the EPA’s annual exposure limit for members of the general public from man-made sources, or about the equivalent of a CT scan on your head once every two years.) The decontamination process involves spraying down buildings and scraping soil, and while several towns have reopened to residents over the years, progress is understandably very slow.

On the first day of our tour, after visiting the TEPCO Decommissioning Archive Center in Tomioka[6] to learn what happened at the reactor sites, we traveled up the road to the Interim Storage Facility Information Center[7] to learn about the estimated ¥30 Trillion (about $300 Billion) decontamination process,[8] which has already been in progress for over eight years and is expected to continue for at least another 30. Cleanup is overseen by the Japanese Ministry of the Environment and managed by the Japan Environmental Storage & Safety Corporation (JESCO), a company wholly-owned by the Japanese government.[9]

JESCO explained that after pressure-washing and/or hand-washing buildings, cars, streets, and any other surfaces that could have accumulated radioactive material, the land is scraped to a depth of 50 centimeters, and the collected material is carried by truck to a secure processing facility that sifts it, separating soil from organic material, such as leaves and wood. Organic materials are burned in a closed incinerator, which captures the ash so it cannot re-escape into the atmosphere. Soil is packaged into container bags, which are labeled with information about contents, radiation levels, and place of origin. The bags are trucked to secure, lined containment areas, where they will be held until a final storage place is determined. The government has assured Fukushima prefecture that contaminated soil will not be stored there indefinitely, but no other prefecture has yet agreed to take it.

To date, about 22% of the original evacuation zone remains closed,[10] meaning some homes have been standing empty without maintenance for nine years, and some will be for many years to come. Even now, homes that survived the earthquake and tsunami are starting to be condemned and demolished. The towns that reopened earlier saw more residents return, but the longer it takes to decontaminate a town, the more likely its residents will have started to put down roots elsewhere. That trend will continue as evacuees increasingly have no homes to return to, raising the uncomfortable question of whether or not it is worth the cleanup cost if only a fraction of the residents will move back.

One long-term Tokyo resident in our tour group said she didn’t want any more of her tax money going to an unrealistic cleanup effort, and that the evacuees should permanently relocate elsewhere. That opinion struck me as a very dispassionate perspective, especially as we were speaking to residents who were returning and attempting to rebuild their lives. However, the economic argument remains: what is the benefit to spending ¥30 Trillion over 40 years (which comes out to roughly $1.8 Million per evacuee) to clean up towns where residents are less likely to return the longer it takes?

Regarding decontamination eight years in, there are many who think (myself included) that there’s not much to be done to buildings at this point that nine years of weather hasn’t done already. A lot of radioactive material has likely been washed away on its own since 2011. That’s not to say cleanup shouldn’t happen, but it is likely that much of what the government hopes to contain has already left untouched areas and traveled downhill and downstream.

No natural areas, such as wooded hillsides, have been remediated yet, but JESCO is exploring process options for that with a “TBD” status on cleanup plans. Given the even lower priority for cleanup in non-residential areas, our tour group discussed the reality of achieving 100% decontamination in Fukushima. From my perspective, it does not seem possible, or at least not economically viable to wash and scrape every last inch of the affected areas measuring more than 1 mSv/year.

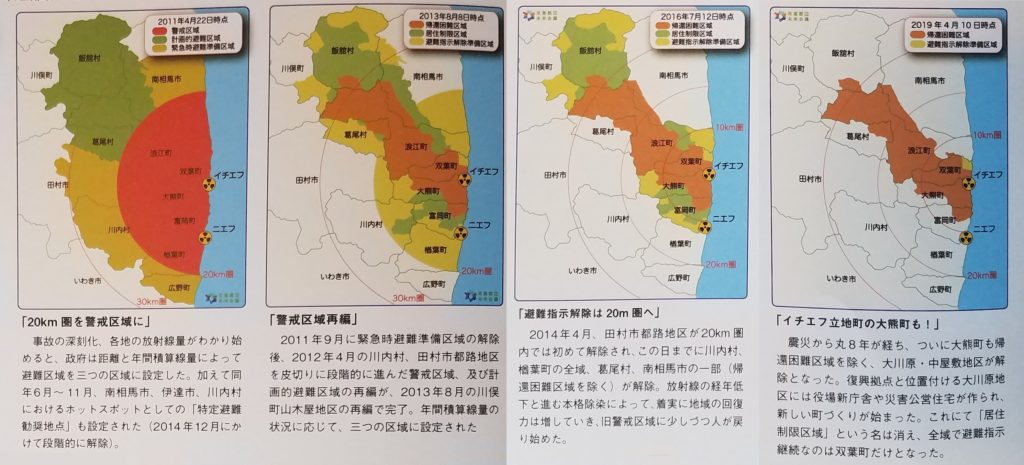

Initial evacuation included everything in a 20km radius from the plant and was then extended to towns within 30km plus a low-lying area to the northwest where winds were blowing.

Maps 2-4 show the progression of areas preparing to lift evacuation orders (yellow), areas presently restricted for living (green), and the “difficult to return area” (orange), which has not yet changed in size.

Images courtesy of Futaba Information Center [11]

So why continue? My personal opinion is that stopping the effort would be even more of a public relations disaster for TEPCO and the Japanese government. As long as remediation efforts are ongoing, they maintain the image of eventual recovery, complete cleanup, and a return to normal. Calling it quits would be an admission of defeat, effectively saying that they are giving up on areas where no one will be able to return for thousands of years.

Unfortunately even for the towns that have completed cleanup and welcomed their residents home, there is still a significant amount of stigma that comes with the name Fukushima. Farmers have trouble selling their food, and tourist spots have trouble getting visitors. In the coming posts we will hear the stories of some of the residents who have returned (and one who never left).

Thank you for reading.

[1] https://japanwondertravel.com/

[2] http://www.ifs.tohoku.ac.jp/edge/radiation/Amount%20of%20radiation%20around%20the%20world%20sep%2008,2011%20EN.pdf

[3] https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/radiation/emergencies/pdf/infographic_contamination_versus_exposure.pdf

[4] http://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/cbn/2011/IssueBrief_Radiation-at-Fukushima_03312011.html

[5] https://web.archive.org/web/20111106113804/http://www.jaif.or.jp/english/news_images/pdf/ENGNEWS01_1318301925P.pdf

[6] https://www7.tepco.co.jp/wp-content/uploads/c5451826b4ad4dafb28bbbdc4752b370.pdf

[7] http://www.jesconet.co.jp/interim_infocenter/en/index.html

[8] https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/04/01/national/real-cost-fukushima-disaster-will-reach-%C2%A570-trillion-triple-governments-estimate-think-tank/#.Xn-2CHJKipo

[9] http://www.jesconet.co.jp/eg/

[10] https://www.pref.fukushima.lg.jp/site/portal-english/en03-08.html

[11] https://futabainfo.com/facility/?lang=english

2 Comments

Passport Overused · March 29, 2020 at 10:12 am

Great post 😁

Alison · March 29, 2020 at 10:53 am

Glad you’re enjoying the series!