Part 1 – Transporting Food

I’ve done it again. Every few years I think “oh, I’ll sign up for a CSA. It will be fun. I’ll cook with fresh, local, and in-season produce, all while supporting local farmers.” While I completely agree with Community Supported Agriculture in concept, I have only signed up for a CSA twice in the past 12 years, and I have been sorely disappointed in myself (not the subscription) both times.

No matter how small a box I order, no matter how infrequent the deliveries I request, my default dinner usually involves going out or ordering in, rather than cooking. Consequently, I never seem to make use of my fresh, local veggies before they go bad, and the result is very expensive compost.

It made sense to try it again this year because Christian and I have gone out together for food exactly twice since the shutdown began in mid-March. On top of that, almost all takeout and delivery options near our house (except pizza) include some kind of plastic packaging, reducing my desire to order food. Could this third time could be the charm?

To CSA or not to CSA

Unfortunately, despite my best intentions, I have once again found myself fighting a lack of discipline, particularly on weeknights when I’m tired and don’t want to cook. I want the warm and fuzzy feelings that come with making responsible decisions for the planet and the local economy, but that desire is at odds with the shame I always feel about wasted food when ingredients go bad before I get to them.

Before I am faced with another decision to opt in or out next year, I figured it would be worth looking at the actual environmental benefits and drawbacks of Community Supported Agriculture. (The irony is not lost on me that all of this extensive research represents time I could be in the kitchen cooking.)

In doing my research for this post, I was pleased and surprised to learn that the concept originated in Japan in the 1960s as a way to support local farms in the face of increased imports, processed foods, and the use of pesticides. The model grew in Europe in the 1970s and finally hit Massachusetts in 1984.[1] As of 2007, there were over 12,000 US-based CSA farms.[2]

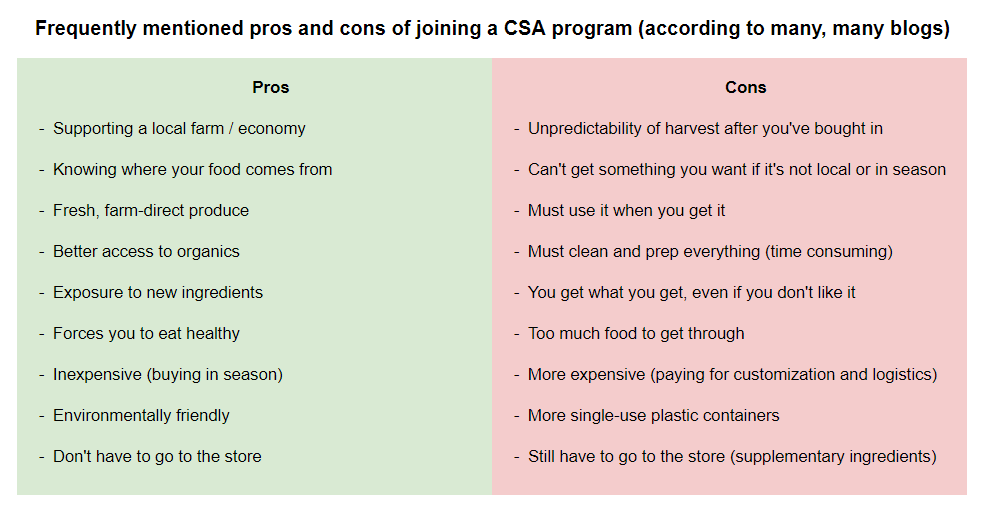

A quick internet search will show you almost as many blogs about the pros and cons of joining a CSA, and I didn’t want to be just one more voice saying that it’s expensive, but you’re getting healthy food; you can’t control what you get, but it forces you to be creative in the kitchen; etc. etc.

These pros and cons are obvious to anyone who has participated in a CSA. What was a little harder to pin down (understandably, because every situation is different) is the actual environmental impacts of choosing a CSA over (or as a supplement to) regular grocery shopping.

Therefore, what I hope to explore in this series are some of the more obscure factors that determine responsible decision-making around food purchases and what role CSAs play in the equation, if any.

Transportation Footprint

The thing that initially piqued my curiosity on this topic was years ago when I heard – anecdotally – that CSAs are actually worse for the environment because, with all the transportation from the farms, to the sorting hub, and then back out again for delivery to a pickup location or to individual homes, the carbon footprint from transportation is actually worse than simply going to a conventional grocery store. Since grocery companies save money through supply chain efficiency (and have whole departments devoted to it), the argument I heard was that the efficiency of moving large quantities of food over long distances once trumps the efficiency of moving smaller quantities of food over shorter distances many times.

Thus far, I have not been able to find any studies that draw this specific conclusion, and I cannot recall where or when I heard that initial anecdote. But let’s look at some additional detail about the carbon footprint of our food transportation to see if that’s even plausible:

A 1980 study stated that fresh produce traveled an estimated 1,500 miles on average “from California and Florida to major terminal markets.”[3] This number has been referenced in subsequent studies (2001) and reference documents (2012), so I’m not sure if that number has changed. My guess would be that it is relatively static, assuming little shift in historical farmland vs. population centers. That number appears to be for domestically-produced food, which is most of what we eat. However we do import about 15% of our food,[4] which required a little more digging into food transportation.

In my research, I learned a new unit: “food-miles” which is the quantity of food, by mass, multiplied by the distance it is transported. The vast majority of our food-miles are by water (58.97%), followed by road (30.97%), rail (9.9%), and finally air (0.16%). Furthermore, “transporting food by air emits around 50 times as much greenhouse gases as transporting the same amount by sea,” so our most-widely used option is fortunately also the least bad.[5]

A 2008 study out of Carnegie Mellon University showed that of the entire food life cycle from start to finish, “transportation as a whole represents only 11% of life-cycle GHG emissions, and final delivery from producer to retail contributes only 4%.”[6] According to several sources and years of research, transportation appears to be a relatively small component of food’s carbon footprint, but highly variable depending on individual circumstances. As one researcher put it, the impact of buying local “is so small that by taking a short drive to pick up local food, you could end up generating more emissions than if you walked to the nearest store to grab something imported.”[7]

So the accusation I heard years ago is plausible, but it also seems to be splitting hairs over a small piece of the puzzle. Research indicates that one of the biggest factors in our carbon footprint is not how far our food travels, but rather what type of food we consume and when. We will pick up there next week, but for now I’ll leave you with a must-have recipe that has been saving my fridge space these past few months (spoiler alert: it’s vegan).

Clean Out Your Fridge: Recipe

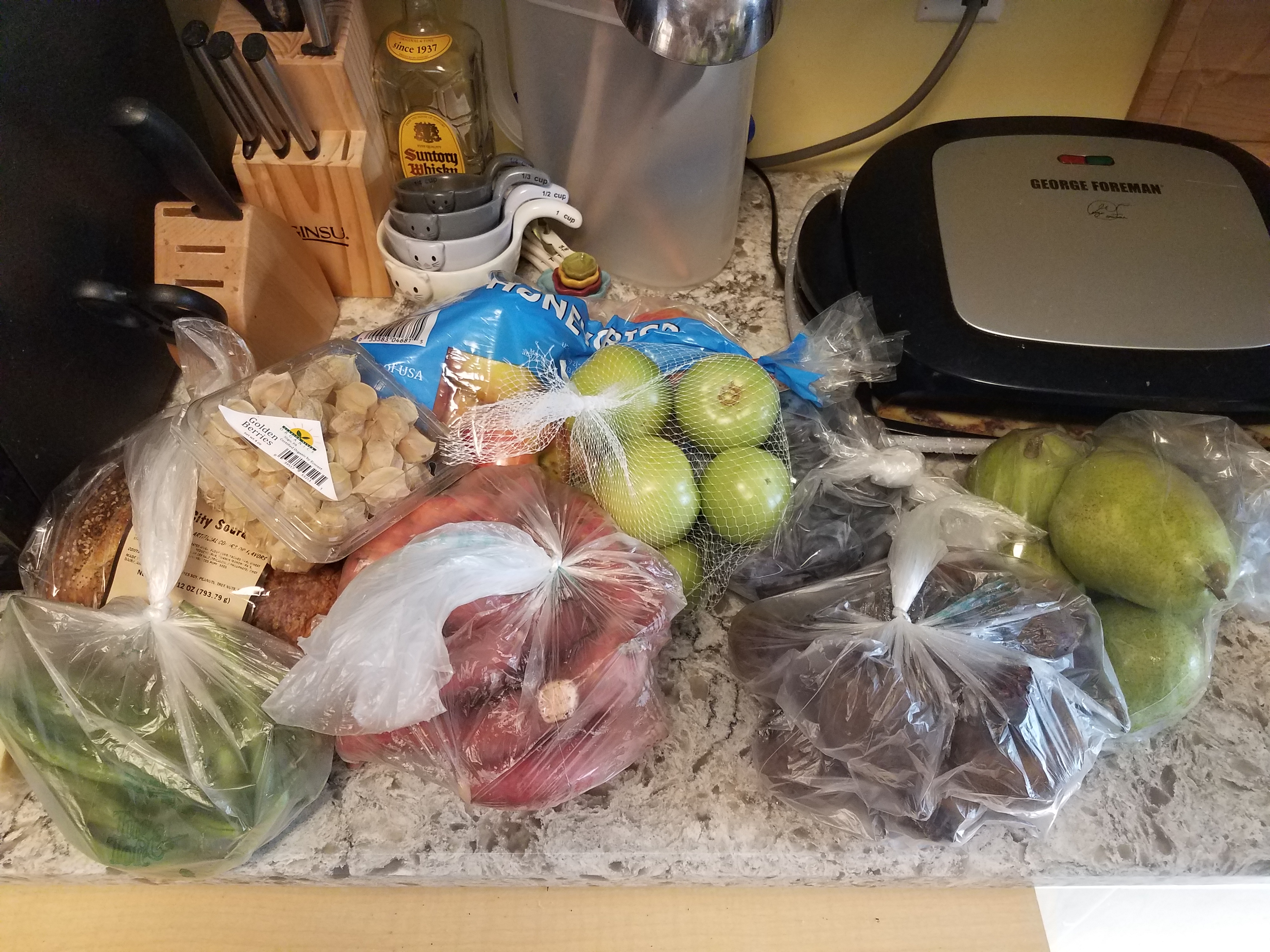

Since I’ve been getting more ingredients than I can reasonably eat between deliveries, a lot of my time has been going to making and freezing soup. One of my favorite cook books, Bad Manners (formerly Thug Kitchen),[8] comes to the rescue again with flexible instructions for to-be-determined ingredients in a completely vegan soup. The recipe below is summarized from their cookbook Thug Kitchen 101, and you should check out the original for more detail and their deliciously foul language.[9]

All-Purpose Veggie Soup

Ingredients:

- 1 Tbs olive oil

- 1 onion, chopped

- 1-2 cups of whatever veggies you’ve got (carrots, bell peppers, parsnips, celery, mushrooms, leeks, or zucchini), chopped

- 3 cups starchy vegetable (russet potato, sweet potato, butternut squash or turnip), chopped

- “3” cloves garlic

- 1 tsp dried basil

- 1 tsp dried thyme

- 1/2 tsp red pepper flakes

- 1 15 oz can diced tomatoes

- 8 c vegetable broth (see recipe here:[10])

- 1/2 tsp salt (I’d suggest more)

- 1 1/2 cups beans (garbanzo or kidney)

- 1 c small, uncooked pasta (shells or stars)

- 5 c ribbons from kale, spinach, or green cabbage

- 1 tsp red wine vinegar

- juice of half a lemon

Heat oil in a large stockpot, adding onions and veggies, sautéing for about 5 minutes. Add garlic, spices, red pepper flakes, and tomato, stirring for a minute.

Add broth and bring to a simmer. Add salt, beans, and pasta, simmering until pasta is cooked per instructions. Fold in the greens and simmer for another 3-4 minutes.

Cut heat and add vinegar and lemon juice. Season to taste.

~

Until next week, happy and healthy eating.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://growingsmallfarms.ces.ncsu.edu/growingsmallfarms-csaguide/

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Community-supported_agriculture

[3] https://www.cias.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2008/07/energyuse.pdf

[4] https://www.fda.gov/food/importing-food-products-united-states/fda-strategy-safety-imported-food

[5] https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food

[6] https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es702969f

[7] https://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/local-organic-carbon-footprint-1.4389910

[8] https://www.badmanners.com/change

[9] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/30820811-thug-kitchen-101

[10] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-corona-edition-part-3/

3 Comments

Peter Crownfield · November 26, 2020 at 4:01 pm

The big climate impacts are embedded in the food and is partly a result of how it was grown. Regenerative organic growing actually sequesters huge amounts of carbon into the soil; at the same time it avoids the direct climate impact of synthetic fertilizers, which have a GHG potential about 300 times that of CO2.

See Rodale Institute’s white paper on organic growing & climate.

[https://rodaleinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/rodale-white-paper.pdf]

Alison · December 7, 2020 at 8:21 pm

Thanks for the Rodale link, Peter.

I look forward to reading it!

The pandemic makes sense trying a CSA – The Bethlehem Gadfly · November 25, 2020 at 12:01 pm

[…] Community Supported Agriculture, Part 1 […]