This Mother’s Day post is dedicated to the woman who taught me to do right by our Mother Earth whenever possible. I’m still doing my best, hard though it may be to determine what “best” is.

Part 3 – Recycle

When trying to find a responsible way to send my mom’s clothing onto its next home or next stage of life, I wanted to do the most responsible thing with it all and ensure that it could still do good somewhere (instead of just winding up in a landfill). Frustratingly, in my research I encountered a morass of misnomers (at best) and misinformation (at worst). Many of us (myself included) are woefully ignorant about what happens with our clothing when we get rid of it, even if we think we know what we’re doing (myself included). This whole deep dive into doing the “right” thing has been incredibly educational for me, which is why I will stress, once again, that the words we use matter. And the word I will be harping on today (as I have in the past) is “recycling.”

When it comes to clothing “recycling” programs, good clothing that can be reworn gets sold in the secondary clothing market; worn or soiled clothing that can’t gets downcycled into rags or fiber. [1] Many clothing collection programs (like H&M’s, [2] which got one bag of unwearable items from my mom’s closet) are referred to as “recycling” programs for sake of ease. However, “recycling” fundamentally means turning a product back into a new version of the same product, the way we can do with metals or glass. Note: I did not include plastic in that list – plastic, which makes up over 2/3 of our clothing (and is expected to approach 3/4 of our clothing by the end of the decade). [3]

The Problem with Plastic

Plastic recycling is something that happens so rarely (and so imperfectly) that it arguably does more harm than good to our planet (and people … and profits, for that matter). I have many other posts on this subject (and regularly devote the month of July to some deep-dive explorations [4],[5],[6],[7]), but I will provide a brief recap of some relevant points here for the purposes of supporting my argument.

Image: [8]

For decades the plastic industry has relied on the public’s misconception that anything labeled “recyclable” actually gets recycled; that belief fuels our consumption of more plastic, believing we have a “get out of jail free” card. Investigations have demonstrated that the “chasing arrows” symbol has consistently appeared on non-recyclable plastic products, despite major players in the industry knowing the truth about that instance of false advertising and choosing to mislead the public anyway. [9]

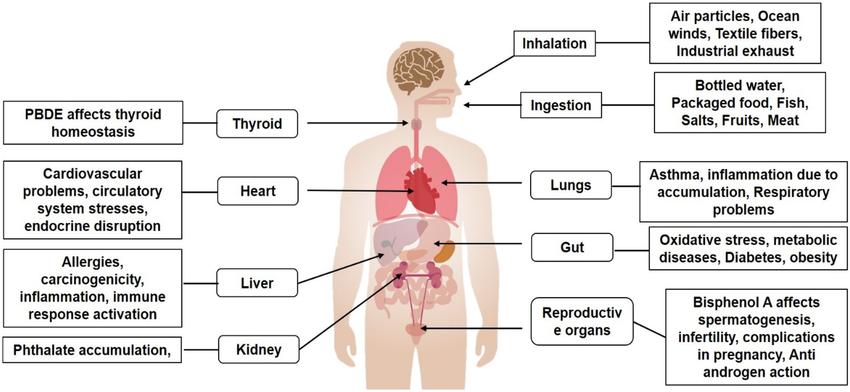

Mechanical recycling of plastic (the only kind that is commercially feasible) only works for a small number of specific types of plastic (#1, #2, and #5 bottles, jugs, and tubs where I live), and the grinding process creates microplastics. [10] Micro- and nano-plastics represent a huge potential health risk, and as more studies are conducted, we’re starting to see more insight into adverse health impacts including cancer, endocrine disruption, and reproductive impacts (e.g. reduced sperm count). [11]

Chemical recycling of plastic (the kind being touted now as a way to deal with “hard to recycle” plastics) has not yet been demonstrated to be economically feasible at scale, and the process as it stands is not a closed loop system, as virgin plastic must be introduced into the mix in order to maintain desired attributes of the material. The vast majority of the time, the resulting oil from plastic pyrolysis gets burned as fuel instead of getting turned back into plastic, thus adding to our climate change burden (which is probably the exact opposite of what people who diligently clean and sort their plastics are hoping to accomplish with their efforts). [12]

Good as New?

Knowing all we do about how little plastic has ever actually been recycled (less than 10%) and how hard it is to do without creating even more harm to the environment and our own bodily health, I was shocked to hear about efforts to recycle fabric (and yes, they actually mean “recycle” in this case). While in Japan last fall with my Climate Lab, [13] we met with Mr. Yamashita Tetsuya of Itochu Fashion System. He described the huge impact the fashion industry has on climate change and global waste streams – and therefore the huge importance of greening the industry as a whole.

Image credit: [14]

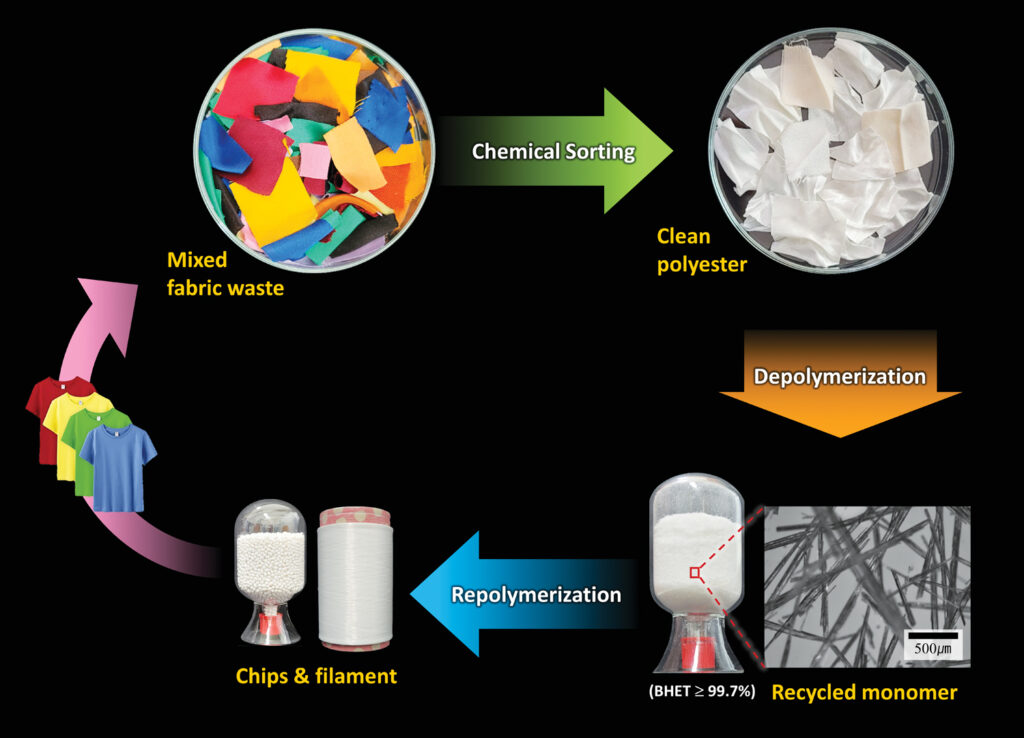

Yamashita-san explained that fabric recycling (i.e. taking old fabric and making it into new fabric again) is difficult, particularly because we have so many clothes made from blended materials. As it stands now, a piece of fabric needs to be 100% of a certain material in order to recycle it (but based on my subsequent research, I believe he may have been only talking about synthetic materials). He told us that new technologies were being explored to recycle mixed fabrics, but there were still many obstacles on that front, including the cost-effectiveness of that process and the difficulty of determining the composition of the fabrics. (Note: if you have 15 minutes, one of my favorite YouTubers, Bernadette Banner, has a very useful – and fun – video on how to determine the fabric content of your clothing. [15])

In preparation for this post, I tried to find what technologies Yamashita-san referenced during our time together in Tokyo. As fabric recycling is a new topic for me, I claim no expertise on the subject, but what I found was mixed (like much of our fabrics). It appears that some early efforts to separate cotton and polyester may have focused on dissolving and discarding the cotton and recovering the polyester for some kind of chemical recycling. A more recent study from researchers at the University of Delaware and the Center for Plastics Innovation seem to have been able to isolate and recover component materials of blended fabrics, including cotton, polyester, nylon, and spandex. [16]

The science behind the process is very cool to read about, with different steps of heating cooling, rinsing, and distilling to isolate much of the original materials, with the intent to recover them for reuse in new textiles. I do, however, have a fundamental skepticism of anything that sounds too good to be true, as is the case here. I wonder about the energy usage and water pollution that would factor into this process at scale – and whether it would be cost-effective to scale it in the first place. Certainly being able to recover and even legitimately recycle textile materials could be a game changer in dealing with our waste problem, but – as is the case with plastic waste already – we can’t do that without also addressing our consumption problem.

Theory vs. Practice

Even if textile recycling worked perfectly, that wouldn’t remove many of the risks associated with our petroleum-based clothing: the climate-altering pollution generated by extracting fossil fuels to make them or the microplastics we shed when we wear and wash them. Once again, it becomes clear that recycling should be our last-resort option, after reducing our consumption of plastic fabrics in the first place – and I recognize that is far easier said than done, especially when realistic ways to do that are limited and/or expensive.

Image credit: [17]

For my part, I’m trying to limit purchases of new clothing and home goods, especially fast fashion items and synthetic materials (including blended fabrics). I’m trying to buy second-hand when possible, but if I’m buying new, buying only 100% natural fiber textiles (and I’m finding that is really hard to do with underwear!) I’m also trying to take good care of my clothing, mending it whenever possible. [18] While sewing was a useful skill learned by men and women for generations, I am surprised how few people can mend their own clothes anymore, which is why I would strongly recommend Bernadette Banner’s book Make, Sew and Mend: Traditional Techniques to Sustainably Maintain and Refashion Your Clothes, no matter your knowledge level – there is stuff in there for beginners and new things to learn if you’ve been sewing for years. [19]

As for the plastic clothes I already have, I’m going to be looking further into getting a microplastic filter for my washing machine. The same friend who told me about the problems with sending second-hand clothing to Africa has the PlanetCare microfiber filter on his machine at home. [20] It is designed to filter microplastics out of the laundry wastewater, and once a filter cartridge is full, the company takes it back to repurpose the plastic (though my understanding is that whatever that will be is still in the works). My friend said he recognizes that it doesn’t catch everything, but even at the 98% advertised, he does feel better about sending fewer microplastics down the drain. I haven’t done much greywater recycling for my garden in the last year or two – in part because of my microplastics concerns – so filtering may get me back into that habit too. [21]

~

There will be plenty more to come on this topic in the future (look out, July!) In the meantime, what questions do you still have when it comes to making responsible clothing decisions? What new thing will you try or learn as a result of this series? I’d love to hear your thoughts below.

And thanks for reading!

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/clothes-of-dead-white-people-part-2/

[2] https://www2.hm.com/en_us/sustainability-at-hm/our-work/close-the-loop.html

[3] https://www.fashiondive.com/news/fashion-brands-synthetic-fiber-use-report/727244/

[4] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-corona-edition-part-1/

[5] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-2022-part-1/

[6] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-2023-the-myth-of-recycling/

[7] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-2024-what-do-we-mean-when-we-say-recycling/

[8] https://www.roadrunnerwm.com/blog/difference-between-upcycling-and-downcycling

[10] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-2024-what-do-we-mean-when-we-say-recycling/

[11] https://magazine.hms.harvard.edu/articles/microplastics-everywhere

[12] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-2024-misnomers-and-monomers/

[13] https://radicalmoderate.online/climate-lab-japan-in-the-classroom/

[15] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qtJ5ukWundY

[16] https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ado6827

[18] https://earth.org/how-repairing-clothes-slows-down-climate-change/

[19] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/57693333-make-sew-and-mend

[21] https://radicalmoderate.online/greywater-reuse-and-laundry-detergent/

0 Comments