Part 1 – Reduce

As John Oliver likes to say at the beginning of each show, “it has been a busy week.” [1] The day before Easter, my best friend helped me sort through six trash bags stuffed with my mom’s clothes. (Major kudos to him, by the way, for dealing with me and the weepy, indecisive mess that I was.) The day after Easter saw the death of one of the world’s foremost advocates for Creation Care. [2] And the day after that was Earth Day. All of these events (plus a gift certificate I received to a clothing company) have kept my mind on clothing and the impacts of our choices: when and how often we buy them, how we care for them, and how we dispose of them. And for something so central to our lives, it is obviously not going to be a simple topic.

Neither is it a new topic for this blog: I’ve previously written about the benefits of reducing clothing consumption, [3] particularly when it comes to synthetic materials, [4] as well as our options for getting rid of textiles responsibly. [5] And because I am so intentional about making responsible choices when it comes to clothing, and because I couldn’t bear the thought of my mother’s clothes going anywhere where they wouldn’t be doing good in their own way, I still hadn’t done anything with them, more than a year after they were orphaned.

The Three Rs

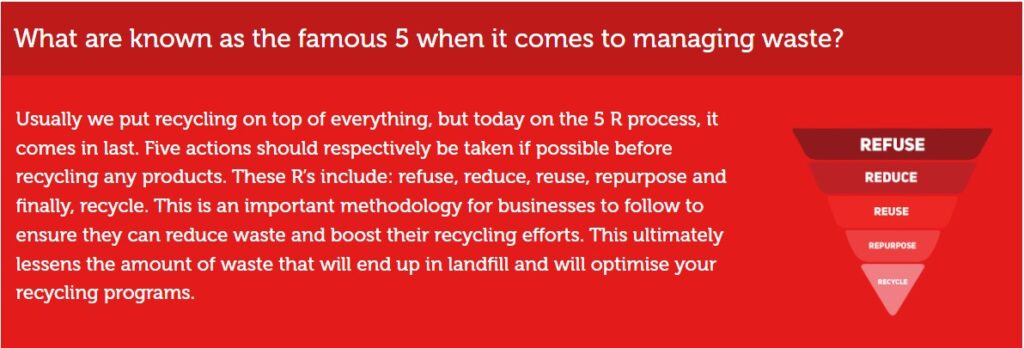

I would guess that most Americans have the words “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” stashed somewhere in their brains, whether or not they adhere to that advice. I would also guess that the majority of those who do think about them don’t realize that they are supposed to be done in that order: with reduction being the first line of defense against waste and recycling being the last resort. After years of research, we know that plastic recycling is either 1) not actually feasible in the case of some types of plastic, 2) not cost effective in the case of others, or 3) creates pollution when it is done (either through the release of hazardous chemicals to air and water in the case of chemical recycling or the generation of microplastics in the case of mechanical recycling). [6]

Image credit: [7]

For decades the plastic industry has led consumers to believe that recycling was a solution to our waste problem, when it isn’t. [8] The term lulls us into thinking that we can consume without concern because as long as we “recycle” our goods when we’re done with them, there will be no environmental repercussions. For that reason, I positively bristle when I encounter the word “recycling” being used inappropriately, which is so often the case with plastic. Precious little plastic (less than 10% of all plastic ever made) has ever been recycled, [9] and in those cases, we’re talking about things like rigid food packaging, not textiles – and plastic makes up a huge amount of our textiles today.

Clothing “recycling” programs can be found at some thrift stores and some clothing chains, such as H&M. [10] They are generally set up to divert donated textiles into three categories:

- Rewearable clothes that are sold as secondhand clothing

- Repurposable clothes that are turned into other fabric products, such as cleaning cloths

- Downcyclable clothes that are shredded and used as insulation, furniture stuffing, or carpet padding

But, again, I take exception to using the term “recycling” because that is not what is actually happening here, and our word choices matter. That term is incredibly seductive, and it can quickly and easily absolve us of our responsibility and our guilt as consumers. What is more often the case than “recycling” is “downcycling,” which describes a final material that has lower quality and/or functionality than the original.

Image credit: [11]

Landfill Alternatives

With that said, it is important to recognize that we as a global society trash 92 million tonnes of textiles each year [12] instead of donating or repurposing them, and collection programs can help divert waste from landfills and offset the need for creating new clothes, rags, or stuffing from virgin materials. Textile reclamation association Secondary Materials and Recycled Textiles (SMART) states that the average American throws away 81 pounds of clothing and household textiles every year, 95% of which can be diverted from landfills (45% as clothing, 30% as rags, and 20% as fiber). [13] I couldn’t bear the thought of my mom’s clothes in a landfill, so of course they weren’t going in the trash. But neither could I bear the thought of sending her much-loved belongings through a shredder. To whatever extent her clothes could still be worn, that was the route I wanted to go. But my mom was a tiny woman, and only her largest clothes fit me, so it wasn’t like I could simply adopt items from her closet, even if I had the space to do so (which I don’t).

We hold onto our clothes in my family for far longer than is normal – I still have clothes from high school that are in good condition. I also have clothes in less-than-good condition: I mend holes created by cats, moths, and general wear and tear; I do my best to remove stains when I can or cover them with a scarf when I can’t. If something is still functional, I will keep using it, even if I need to retire it from professional situations. For that reason, my interpretation of the term “gently used” is a little different than what may be intended by your average thrift store. I have absolutely purchased thrift store clothing that has small stains or imperfections – but as we were sorting, my friend was notably stricter with the quality control, putting item after item into the “not good enough to donate” bag headed to H&M for “recycling.” He was doing the necessary job of making decisions I couldn’t but still broke my heart slightly each time.

I absolutely understood his point: dignity is important, and I agree with that. Of course people with limited means shouldn’t be reduced to buying (or even being given) ratty clothing that makes them feel worse about themselves. Nevertheless, my brain continued with its justifications: isn’t it better to give someone the option of picking something that is good quality and functional (even if it’s not perfect), instead of making that decision for them (especially since they know better than we do what they need)? I personally would take a high quality wool sweater with a moth hole that can be patched instead of a brand-new, fast-fashion shirt that will fall apart after five washes – I would make that choice any day of the week (but I also recognize that others might not).

Image credit: [14]

The thrift store where these clothes were headed is an independent one that I first learned about when I was doing my own Marie Kondo tidying efforts four years ago. [15] I picked them then not just because of their efforts to support trafficked women, but also because of how intentional they seemed to be with the donations they received: they would sell what what good quality items they could on the rack in their store; they would sort and resell what they could (as mentioned above) for rags or stuffing; but there was another tier in between – functional, imperfect clothing would be sent to developing countries. I was confused and disappointed not to see that option there anymore when I revisited their website, but once again my best friend explained how there are some distinct downsides to that practice – and that is where we’ll pick up next week.

~

Do you donate to and/or buy from thrift stores? What has been your experience with garment quality, and where do you draw the line on “gently used”? I’d love to hear your thoughts below.

Thank you for reading.

[1] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3530232/

[2] https://www.cathstan.org/faith/pope-francis-lived-up-to-his-namesakes-love-care-for-creation

[3] https://radicalmoderate.online/zero-waste-lent-week-5-clothing/

[4] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-corona-edition-part-4/

[5] https://radicalmoderate.online/tidying-up-week-2/

[6] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-2024-what-do-we-mean-when-we-say-recycling/

[7] https://www.circlewaste.co.uk/2020/09/16/what-are-the-5-rs-of-waste-management/

[8] https://www.npr.org/2024/02/15/1231690415/plastic-recycling-waste-oil-fossil-fuels-climate-change

[9] https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2018/03/06/only-9-of-the-worlds-plastic-is-recycled

[10] https://www2.hm.com/en_us/sustainability-at-hm/our-work/close-the-loop.html

[12] https://earth.org/statistics-about-fast-fashion-waste/

[13] https://www.smartasn.org/resources/frequently-asked-questions/

[14] https://repurposedpgh.com/

[15] https://repurposedpgh.com/

0 Comments