<– Start at the beginning of the Climate Lab series

Japan, Part 2 – In the Field

Japan is a world of paradox: awash in a mix of tradition and modernity, expressing fascination with other cultures while remaining a very insular society. I recently wrote about aspects of Hayao Miyazaki’s movies and explained why paradox is not a bad thing, but rather something expansive, inclusive, and far more reflective of the world in which we live. [1] For that reason it should be no surprise that a country as complex and contradictory as Japan has work to do in each of the oft-divided climate camps: countries that can mitigate their climate impacts and countries that must adapt to the impacts of others. Neither mitigation nor adaptation is easy, but both are necessary – and any country doing both is worth studying in more detail.

Our Climate Lab was funded by the Japan Foundation, and their team pulled out all the stops for our week in Japan. We traveled in and out of Tokyo and met with representatives from various levels of government and the national broadcasting company to better understand the various types of efforts underway to educate audiences on emerging issues and to promote behavior change in a changing world. But you can trust me when I say that behavior change is not something that comes easily for humans in general – especially not in Japan. During the two years I lived there, I had very little autonomy to approach my job in creative ways that might have been more effective – things are largely done the way they’re done with little wiggle room.

Cool Biz

I moved to Japan in July 2006, and in almost every introductory meeting at every school where I would be teaching, someone explained the presence of short-sleeved shirts in the office by proudly stating that they were doing “Cool Biz.” I had no idea what it was or why everyone was talking about it, but I eventually surmised that it was a summer dress code that allowed for cooler professional attire. I didn’t know that it was in order to set air conditioner temperatures higher in the summer to save energy – I learned that when we met the man behind the movement at the Ministry of the Environment as part of our field visits with the Climate Lab.

Mr. Doi Kentaro, Director-General of the Global Environment Bureau, described the Cool Biz initiative as part of Japan’s promise to reduce emissions by 6% under 1997’s Kyoto Protocol, [2] through renewable energy, better appliance standards, and lifestyle changes. Cool Biz was not a new concept – in fact, it was started in the 1970s during the oil crisis, but it failed because it was seen as self expression. In Japan, professional attire in the business world is like a uniform – it means you’re taking your job seriously. (I didn’t realize when I lived there that makeup was part of the uniform for women, and I think it legitimately bothered some people that I didn’t wear any.)

Efforts to save energy through lifestyle changes would need to be widely accepted to be effective, which is why the Ministry of the Environment created a public initiative called “Team Minus 6%” to drive behaviors that would support decarbonization, doing so in a visible, public way, with people joining up for the good of the country. But it is hard to drive social change without cues from the top, which is why the Ministry enlisted then-Prime Minister Koizumi and the chairman of the Japan Business Federation to give explicit instructions about adopting Cool Biz standards… and then do it themselves. Cool Biz outfits were featured in a fashion show at the World Expo in 2005, and the term was in the top 10 buzzwords of the year. [3] Suddenly I realized why it was still a hot topic of conversation the summer I arrived.

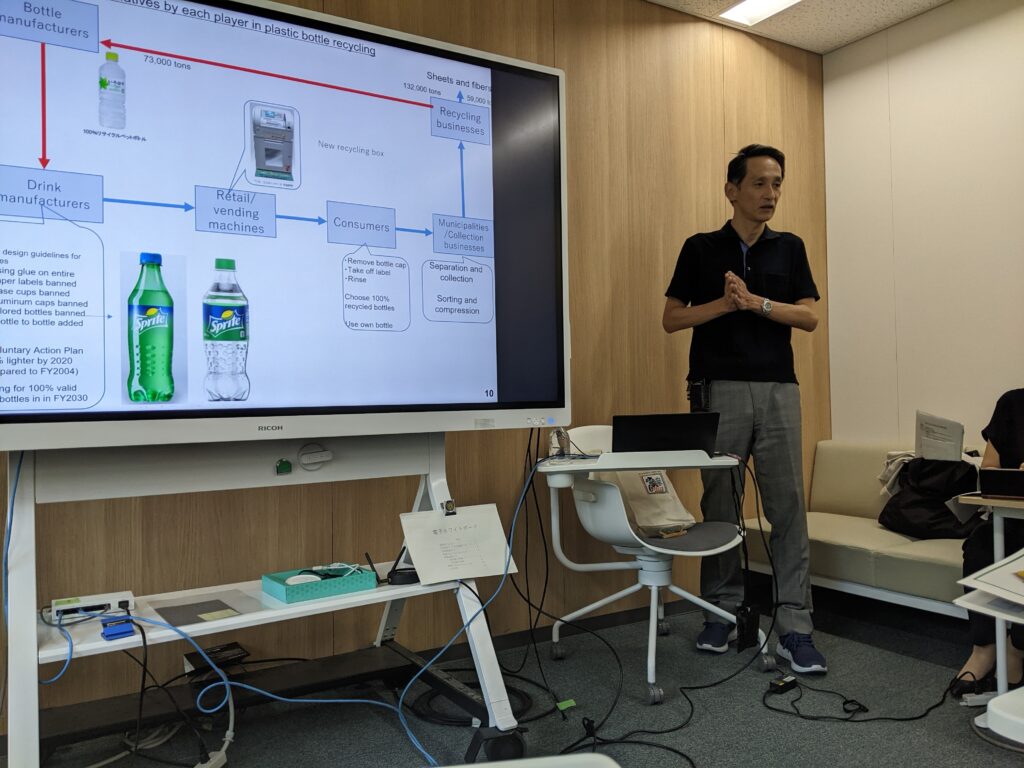

It was surprising to walk through the Ministry office and see such a casual dress code. Although it was September in Tokyo, it felt hotter and more oppressive than I remembered in the height of summer almost 20 years ago. The air conditioning was most definitely not set to the official Cool Biz guideline of 82 degrees F, but it was notably more comfortable than icy American office buildings. A significant shift in Japanese business culture did seem to have caught on, even at the highest levels of government, and now the Ministry has their sights set on other initiatives that will involve education and motivation to change behaviors, notably reductions in single-use plastic consumption and better recycling of that which does get used. I wish Doi-san and his team the best of luck on that front, since change is hard enough back home.

(Mis)Information

Education is a massively important component for supporting successful shifts in cultural norms. People need to understand why a certain initiative is in place in order to better accept changes to their routines, but – at least in my own experience – many people in Japanese society can be reluctant to ask for more background information, as it can come off as rude or contrary. At the forefront of education is public broadcasting company NHK – a channel I watched regularly when I lived in Japan and still stop to watch briefly whenever I’m shopping at a Japanese grocery store in Pittsburgh’s east end.

NHK broadcasts a range of educational programming, including content regarding the increasing number of natural disasters across the country. In situations where minutes count, automated notifications now pop up on screen until an anchor can join with timely information about the emerging danger and what actions locals should take to stay safe. NHK also airs content about disaster preparedness, stressing the concept that these events could happen to anyone. They show documentaries about disasters that took place in the past, illustrating how people could have been better prepared and stressing the importance of doing drills and having disaster plans.

Working in the field of public health, I know that it can be difficult to convey complex information without also making the guidance confusing, especially when evolving situations result in changes to the original guidance. In times like that, it can be difficult for people to know where to turn for information, especially with the rise of fake news and misinformation online. Japan is heavily reliant on the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, with about half of Japan’s population using it. We learned that because of how the platform is structured, monetization drives a desire to get impressions by any means necessary, and one result can be something called “impression zombies.”

These users farm content from other accounts and repost it as their own; they also interact with existing content to drive views of their own posts. At its core, it’s not necessarily harmful – aside from cluttering newsfeeds and making information from reliable sources more difficult to find – but some create patently false, inflammatory information in order to drive up views. When that content includes misinformation about natural disasters, critical assistance for people on the ground can be disrupted. [4] NHK sees it as their job to debunk false information, but the scales are incredibly unbalanced. Mr. Yabuuchi Junya, a news desk reporter and senior commenter, told us that there are close to 390,000 spam posts with inaccurate information on spoofed accounts a day, while his team only has about three or four people working on debunking. Interestingly, Yabuuchi-san reminded us that those posting zombie content aren’t bad people; the system they’re using is bad and encouraging bad behavior.

Grassroots Connections

In a world with such rapidly evolving technology, it is often difficult to know whom to trust, and it can be easy to fall victim to false information, whether from passionate but misinformed humans or AI-generated DeepFakes. Ultimately, no matter how trustworthy information may be from science-backed government initiatives or thoroughly fact-checked public broadcasting, we humans are hard-wired for interaction with other humans, and we are far more likely to trust or collaborate with someone that we consider “in” the same group versus someone who is “out” of that group. For that reason, while unbiased, trustworthy, centralized sources are essential for disseminating relevant information quickly from the top down, it is also essential to have resources that engage effectively from the bottom up, meeting people where they are and addressing unique challenges in their given community.

Sumida Ward in Tokyo is home to about 276,000 people, living at an average elevation of 0 m, on top of 90% impermeable surfaces. Tokyo saw about 1.4 times more rainfall in 2015 than in 1975, with fewer rainy days bringing more rainfall, making flooding a more common event. When flooding happens, it takes about two weeks for water to recede, which is why a Sumida-based organization called People for Rainwater is focused on community-level rainwater management. During a walking tour led by Ms. Sasagawa Michiru, we saw a distributed rainwater management system, made up of catch basins, gardens, and storage tanks. The set of tanks located throughout the community stores approximately 26,780 cubic meters of water, and the water can be accessed with a hand pump when needed to water gardens between rains.

In addition to the infrastructure, the organization leads community-based educational activities to help people learn about the rain cycle, how to build and maintain storage systems, to support disaster preparedness, and to create healthy habits related to water use. [5] These adaptation steps are necessary from a quality of life standpoint for the residents of Sumida Ward, but their efforts also serve to highlight the impacts of climate change currently being experienced, even in highly developed countries such as Japan. This collective effort is distinct from the climate mitigation initiatives that people have opted into over the years, such as Cool Biz: it is necessary from a health and safety standpoint with very immediate consequences for not doing anything. It also drives distinct value for the community because it is informed by residents’ concerns and perspectives in ways that top-down efforts fundamentally aren’t.

~

Broad perspectives are essential when addressing climate change, and that’s exactly what we got when we continued to a place in Japan I had never been before: Okinawa. We will pick up there next week, but in the meantime thank you for reading!

The Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab [6] is a program of the East-West Center, [7] with support from the Japan Foundation. [8]

As always, content on this blog reflects my personal views, and not those of any organization with which I am associated.

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/the-world-of-miyazaki-paradoxes/

[2] https://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol

[3] https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2005/jun/01/japanese-get-a-dose-of-cool-biz/

[4] https://unseen-japan.com/impression-zombies-japan-social-media/

[6] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/projects/indo-pacific-leadership-lab

0 Comments