<– Start at the beginning of the Climate Lab series

Japan, Part 1 – In the Classroom

I couldn’t believe I was nearing the end of what had been an incredible, difficult, and life-changing year. It hadn’t even been eight months since our Climate Lab cohort met in person for the first time in Honolulu, and suddenly we were all together for the last time in Tokyo. As we assembled for what would be a very intense week together, I was asked to share some remarks during the opening ceremony, speaking about my experience so far and what I hoped the next few days might hold. I was also asked to do that in five minutes, which is an amusing concept: anyone who has stuck with this blog series, through the previous 17 posts, totaling over 29,000 words, will know that brevity is not my strong suit.

To be fair, though, there has been far more in this program, from classroom content to my own insights, than I’ve been able to cover, even in this expansive blog series. There are many more threads I hope to weave into other posts in the future, while I focus on my core lessons here in the formal “Climate Lab” series. And the core lesson I spoke about in my five(ish) minutes was the concept of leadership: it is not a title granted by someone else but instead a duty assumed by the person doing it; it is not an act performed not because someone wants to do it but instead because they see it needs to be done; it is not a fixed label that endures forever but instead changes dynamically with the situation; and it does not require perfection but instead a willingness to try imperfectly while exploring the unknown.

Photo credit: Adi Litia Nailatikau

And given that thought, it was clear that the end of this program also represented the beginning of whatever we do next. We still had a week together to round out our year of learning, during which we would be exploring methods of climate adaptation and mitigation, as well as all the challenges that come with the process: equitable decisionmaking, meaningful education, and learning from mistakes. I made it clear that this program was not attempting to teach us the answers (because nobody knows those, yet); this program was teaching us skills and approaches for finding the answers to this unique crisis in human history. And considering all of that, I was excited to see what in the coming week would get me outside my comfort zone and help me do my work more effectively.

It’s All Relative

I often consider Japan the site of my environmental awakening. Certainly, my mother laid ample groundwork with all the education and activities we did together while I was growing up, but I always remember the feeling I had in my first apartment: trash sorting instructions and collection schedule posted on the wall in my kitchen, all of my neighbors participating as expected (and knowing if you didn’t), and a very real sense of small actions adding up to some big and important collective outcome. For years after I moved back to the US, I thought of Japan as a shining example of embedded sustainability, and I harshly judged all of America’s shortcomings in environmental action, especially related to our ineffective and underutilized recycling systems.

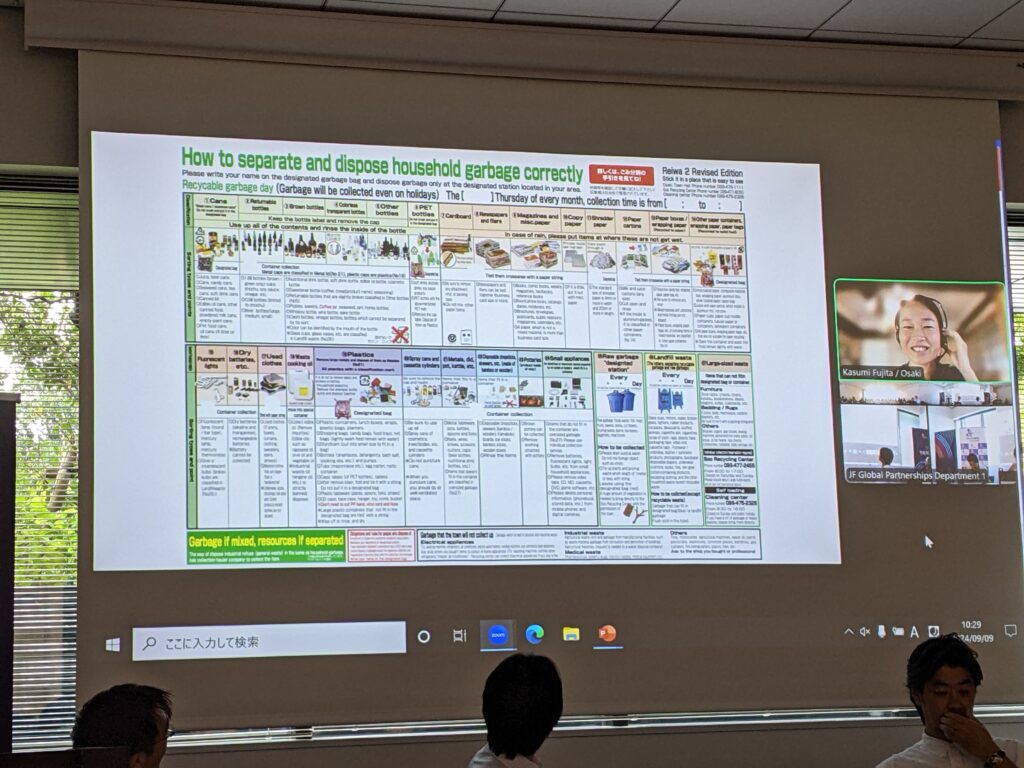

Less than an hour after I elicited some giggles about the personal impact of Nishiaizu’s seven trash categories in my opening remarks, our cohort met a representative from Osaki, a town in the southwestern prefecture of Kagoshima that has achieved a recycling rate of over 80%. Ms. Kasumi Fujita, who spearheaded the town’s recycling program, explained that the average recycling rate across Japan is less than 20%. Osaki collects no fewer than twenty-seven categories, with a very small amount of waste actually going to the landfill: if it can be recycled or composted, it is. Consequently, the town did not have to build an incinerator, as they had originally planned, and they have extended the life of their one landfill for another 40 years. [1]

Fujita-san explained that each municipality governs itself, and there is not a lot of top-down policy from the national government pushing improvements like these across the country, despite the clear benefit of better waste management while living on an island. Even in Osaki, education efforts to encourage participation have represented a long process, and they continue to host small discussion groups to teach the younger generation about the importance of this work and to figure out ways to sustain and improve upon it. And, with all credit due to the amazing work of Fujita-san and the people of Osaki, there is absolutely room for improvement – not so much on the waste management side, but on the consumption side.

Coming from Pittsburgh (by way of Fiji, in this program), I experienced no small bit of horror at the sheer amount of single use plastic packaging in Japan. When I lived there I used to believe, as many do, that recycling is a realistic and effective way to deal with plastic waste. It is not, and there is a wealth of detail worth exploring in any of my “Plastic-Free July” posts. [2] Instead, the real issue to address (which will also help with waste management efforts) is reducing consumption in the first place. It’s a topic that came up multiple times over the course of the week, in meetings with representatives at multiple levels of government – municipal, prefectural, and national. And I was reminded each time that public perception, attitudes, and behavior are all incredibly difficult things to change, no matter the cost of staying the same.

The Only Thing Certain is Change

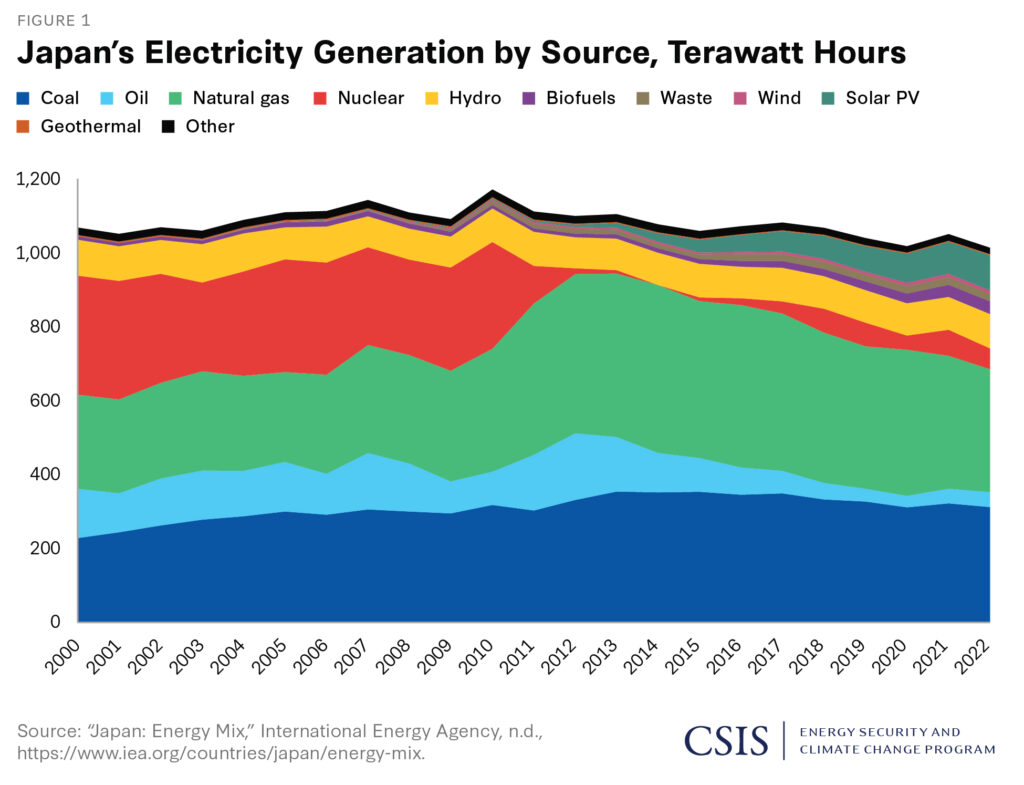

The truth is, I wasn’t even expecting to focus on plastic during my time in Japan with the Climate Lab; I was expecting conversations about energy generation (especially given our pre-departure coursework on decarbonizing Japan’s electricity grid). But the two are inextricably linked, since the oil and gas industry is looking to plastic production as an economic life raft as more countries move away from fossil fuels for energy. The more the world transitions toward renewable energy, the harder the marketing push we will see from the plastics industry telling us that plastics are essential to maintain our quality of life and that plastic recycling is a realistic solution for offsetting our consumption, with no downsides whatsoever. Again, those utterly false and greenwashed claims are a subject for another time, but the issue of consumption (no matter the product) remains a central issue when it comes to sustainability.

Image credit: [3]

The transition toward clean energy in Japan represents a complex challenge but also an immediate one. Speaking in very broad strokes, when discussing climate change at the international level, there is generally a dichotomy between countries that emit larger amounts of greenhouse gases and countries that feel larger impacts from climate change. In short: there are countries that can make significant global impacts by mitigating their emissions and countries that must adapt to the consequences of other countries’ emissions; the more mitigation happens, the less adaptation has to happen. (Similarly, the less mitigation, the more adaptation.) That’s not to say the United States isn’t already experiencing devastating impacts from climate change – we absolutely are [4],[5] – but countries facing disproportionate impacts tend to be small island nations. [6]

Japan, interestingly, has a foot in each camp: it is among the world’s top five economies [7] with the seventh-highest global CO2 emissions in 2023, [8] but it is also an island nation feeling acute impacts of climate change. One of the biggest opportunities – and challenges – Japan faces when it comes to decarbonization is its reliance on imported fossil fuels. Until 2011, nuclear energy represented about one third of its grid mix, but it is understandable why faith in that safest of energy sources has chilled. Nevertheless, it does appear that nuclear will still represent part of Japan’s ambitious path to achieving net zero emissions by 2050, along with a tripling of solar capacity. [9] Certain large members of the tech sector are also looking to offset their own growing energy use with new deployments of renewables as well as energy efficiency and demand-response measures that can reduce and smooth consumption, respectively. [10]

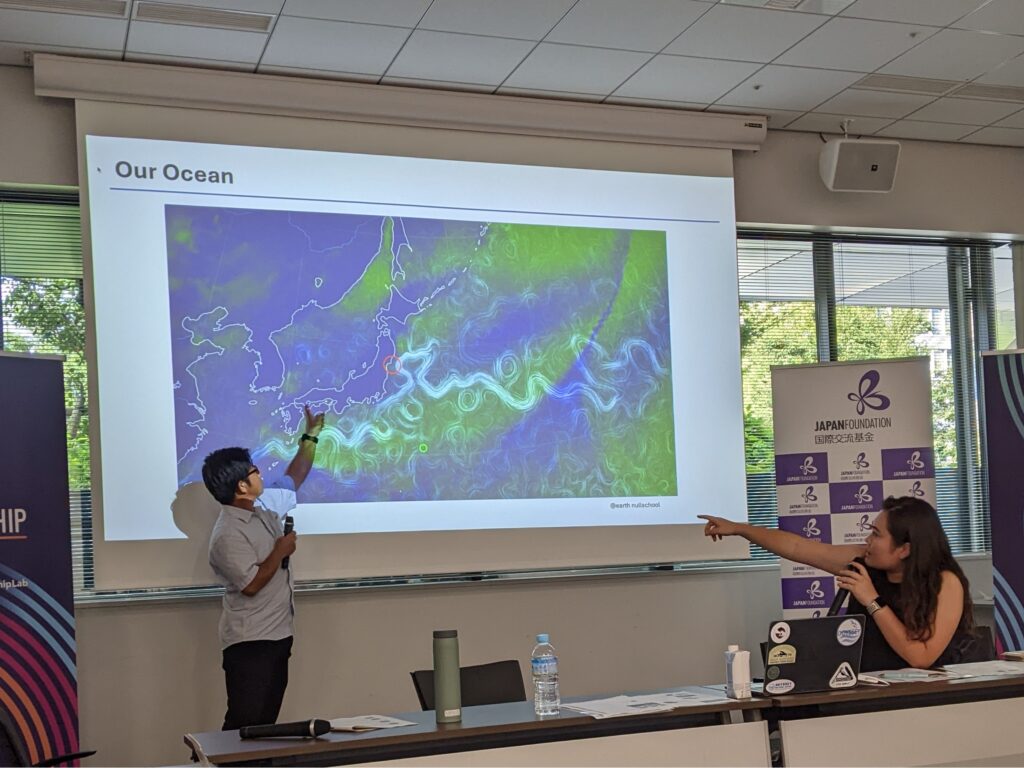

But while Japan mitigates emissions, its residents must also adapt. Changes in weather have not only impacted safety and housing, but food and culture. I experienced first-hand the importance of tradition in Japanese society, as well as strong connections between place, livelihood, and identity – and all of those things are threatened with climate change. On our first day in Tokyo, we met a seaweed farmer, Mr. Futoshi Aizawa, who has won awards for his nori (the dried sheets of seaweed you may have eaten wrapped around sushi). [11] But changes in ocean temperatures and nutrients are contributing to an unfavorable environment for this essential Japanese food: he explained that while 10 billion sheets were produced in 1998, that number dropped to 4.5 billion in 2020. His efforts now include adopting practices from other countries, such as a regenerative aquaculture system studied in Palau, [12] and doing community-based education around the intersection of Japanese culture and heritage, local ecological knowledge, and environmental stewardship.

~

Japanese cultural identity is woven together tightly with the concepts of place and purpose, as is the case with many nations throughout the Pacific. But for many of these societies, their traditions, their homes, their people, and their very existence are at risk with as little as a 1.5 C rise in global temperatures. As we prepared for our last week together in the Climate Lab, we were encouraged to explore with open minds: to look for similarities with home and other places we had visited during the year, to get outside our comfort zones and challenge our own assumptions, and to remember that a critical component for progress is trust.

Tune in next week when we will look at some of the lessons we learned on the ground in Tokyo and further afield.

Thank you for reading!

The Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab [13] is a program of the East-West Center, [14] with support from the Japan Foundation. [15]

As always, content on this blog reflects my personal views, and not those of any organization with which I am associated.

[1] https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/03/1148011

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-2024-what-do-we-mean-when-we-say-recycling/

[3] https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-japan-thinks-about-energy-security

[4] https://www.cnn.com/2025/02/13/weather/california-rain-wildfires-burn-scars-threat-hnk/index.html

[5] https://www.cnn.com/2025/02/13/weather/california-rain-wildfires-burn-scars-threat-hnk/index.html

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_GDP_(nominal)

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_greenhouse_gas_emissions

[9] https://www.japan.go.jp/kizuna/2024/01/together_for_action_japan_initiatives.html

[11] https://nihonmono.jp/en/article/12197/

[13] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/projects/indo-pacific-leadership-lab

0 Comments