<– Start at the beginning of the Climate Lab series

Fiji, Part 5 – Insights, Continued

If I have one true core competency, it is procrastination – and I’ll go a step further and specify that it is perfectionism-based procrastination. [1] I suffer from analysis paralysis, always feeling like I need more data before making an informed decision or even stating an informed opinion (on this blog, for instance). I recognize that it is impossible for a tiny human brain to hold the sum total of all human knowledge, but that hasn’t stopped me from trying. My drive for wanting to do that is (at least these days) a recognition that any decision I make will send ripple effects out into the world, and the more informed my decisions are, (hopefully) the more responsible and less harmful they will be.

Of course, the other side of the coin when it comes to perfectionism is the fact that it takes time and resources even to attempt perfection (since it can’t actually be attained – shh!) In the field of public health, where I spend my days, you can’t afford to wait for perfect information before making a decision about how to protect people: you have to make the best choice possible given the limited information available at the time, and then when more information becomes available, you can refine your approach. And so it is with climate change – if we waited for perfect information or a perfect plan, the tradeoff would be time, during which more irreparable damage would be done to our planet, with even more homes and lives lost in the process.

Unfortunately, it’s a given that when you’re working against the clock with increasingly higher stakes, critical information and perspectives will be left out, which can lead to serious oversights – oversights including unconsulted stakeholders, unconsidered consequences, and unasked questions. That’s why (as we read in one of our earliest assignments for the Climate Lab) it is incredibly difficult to build an approach that is both scalable and just. [2] Scalable action is necessary because the climate crisis demands sweeping changes on a short timeline; just action is necessary because every human deserves the dignity of being involved in decisions that will impact them.

Taking the lead vs. taking direction

Struggling to balance these conflicting aspects of problem-solving is a challenge that we’ve discussed throughout the program, but one major question hung over all of our interactions in Fiji: “who gets to make the decision?” Having spent years in community engagement work, I know that communities always understand their issues better than someone from the outside, and I also know (having been that outside person who comes with the best of intentions) that outside help is not always grounded in perspectives that are based on community-level experiences or priorities. Similarly, I have seen communities and nonprofits alike scramble for whatever limited aid money might be available and, in doing so, create a project or initiative that may not actually address a relevant priority for them or be helpful in a meaningful way.

Outside perspectives (with best practices and lessons learned from elsewhere) can absolutely contribute to more effective approaches – that was the focus of my blog post on diversity last fall, [3] and it’s something I encounter at work on a regular basis (it’s part of the point of having a board of directors). But in my organization’s case, there’s still clarity that I am still the one who sets the goals (with input, of course), and I make determinations about whether a certain course of action will help us achieve those goals. It’s far more complicated than that at the community level when you’re asking really difficult but really critical questions like “how do you define success in this situation?,” “whose definition is it?,” and “on what timeline are you evaluating success?”

During the visit to Daku, we heard about their need for a higher sea wall and better flood gates; we also heard that money for adaptation is difficult to obtain. It was unclear how long the new sea wall would last or how high the sea levels would rise during the course of its useful life; how many people would be helped and how expensive the venture would be. Those are objectively good questions, especially for an organization that might consider funding such efforts. But for a community that doesn’t consider relocation an option, it’s unclear if they’ve even asked themselves these questions – we certainly didn’t ask them.

During the visit to Anitioki, we saw the sea wall under construction, without the expertise of an engineer. Years of community work has led me to believe that communities should be able to make their own choices about a course of action whenever possible, with an outside organization (like my own) supporting their goals instead of taking the lead. But aren’t there situations like this one, in which content expertise (e.g. engineering) is necessary, or am I just assuming that these communities that have lived on that land for generations don’t know what they’re doing? That’s also a question we didn’t ask them.

“I’m from the government, and I’m here to help”

I absolutely recognize that for a community that is raising its own money for building materials, hiring an engineer is an added expense, possibly an unnecessary one for all I know. But the question I took away from that experience is how I can offer meaningful support when I see gaps in an approach (and that goes for Fiji, Pittsburgh, or wherever else in the world). Certainly if a person, community, or organization asks for help, that’s one thing; but if they don’t, that makes things more complicated for someone who wants to help. I have to ask: to what extent am I imposing my own values or perspectives on them with my “help”? And if I know for sure that they have made assumptions based on limited information, how can I (and to what extent should I) push back on those assumptions without discounting their lived experiences?

Despite my own professional qualifications, I don’t have the lived experience of some of the communities I work to help every day, and it is important to remember that their expertise is simply different than mine, not less valuable than mine. Interestingly, I experienced the flip side of that situation while in Fiji when I checked my email and saw that I had received some difficult questions from a potential funder. I know this person wanted to see an initiative of ours succeed, but receiving critical feedback – even challenging questions – can be a difficult experience. Knowing that the reason for these questions was not to take over our project but to help increase our chances of success helped me reframe the situation.

Consequently, I returned to our classwork with the thought that if I see a need to humanely stress-test assumptions in a community, listening to their needs and goals first, and then asking relevant probing questions, not dictating solutions, seems like a valuable place to start. Questions asked by someone with a different perspective (a higher-level view, a longer timeline) don’t inherently represent a challenge to your goal, though they can feel that way. Depending on who is asking the question and why, more thoughtful discussions – informed by more diverse perspectives- may result in an augmented goal, but possibly one that is broader and can garner more support.

With all that said, it is critical to note that there are absolutely times when the approach is not fair because of a power imbalance so extreme that it skews the goal toward something that isn’t in the best interest of everyone who will be impacted. I was recently talking about the value of getting more diverse perspectives to the table when a teammate commented that it’s important to remember whose table it is in the first place. It’s an excellent point because I’ve seen many times in my own work that just because a process is designed to appear equitable, it doesn’t mean it is. So the question remains: what’s next?

Where do we go from here?

At the end of our week in Fiji, instead of giving a presentation on what we had learned, our cohort decided instead to take the time to host a series of mini talanoa sessions with our attendees, rotating them to different tables and hearing their perspectives of our work thus far (looking back to Hawai’i, looking around in Fiji, and looking ahead to Japan). Themes from those conversations served as an effective summary of our learning to date and lay the groundwork for our efforts to come. The following concepts especially resonated with our group:

- Structure is important for dealing with conflict and issues, but voices outside the structure that aren’t explicitly brought in won’t be heard

- Communicating decisions and rationale back down the levels of government is as important as communicating concerns and requests upward

- Centering culture and tradition in conversation, while weaving in relevant facts, is valuable for establishing a stable foundation from which to develop solutions

- Options for climate change adaptation cannot be evaluated in isolation – a holistic view of different stakeholders, priorities, and possible impacts is essential

The challenge laid at our feet for the remaining months of the program was to create something of value to give back to the communities we’ve met and/or to pass along to the next cohort in the program so they can hit the ground running in October. Certainly, I do not have the expertise to develop equitable, meaningful, and lasting solutions specifically for Fiji – nor should any of us in our cohort be thinking about dictating a path forward after everything we’ve heard about the importance of centering community voices in this kind of work. But I wanted to explore the concept of developing an equitable decision-making framework: not an answer, but a tool for arriving at an answer.

To be clear, I don’t particularly enjoy when someone points out my inaccurate assumptions, errors of logic, or blind spots, but I absolutely recognize the value of that pushback in making me a more effective leader. My priority at work is the success and wellbeing of my organization, but I also recognize that we will be more effective in achieving our mission if we coordinate with other organizations that share higher-level goals (which was the crux of my graduate research [4]). Recognizing that I have benefitted from difficult questions that stress-test my assumptions, and recognizing that more valuable questions are more likely to come from a more diverse set of stakeholders, it seems that this tool should take the shape of some kind of framework for guiding unlikely partners through the process of identifying common goals and crafting strategies and tactics for achieving them together.

Thus far, I haven’t moved much past the idea generation and early research stages of this project, though I have some good benchmarks identified. I have no idea if or how it would be adopted, or if it would be useful for anyone other than myself. But it will be a starting point, and given the dwindling timeline of this program, it will absolutely be heading out into the world before I have it perfect and polished – and, if that means I can get valuable feedback on my approach as I’m developing it, I also see why that’s a good thing.

~

I had many more thoughts to share in this post, but they will have to wait for another time. After the week was over, our cohort went our separate ways with many things to ponder before our next virtual session. Meanwhile, Christian and I stayed to explore Fiji, which is where we’ll pick up next time.

Do you have thoughts or suggestions about my project? I’d love to hear your ideas below.

Thanks for reading!

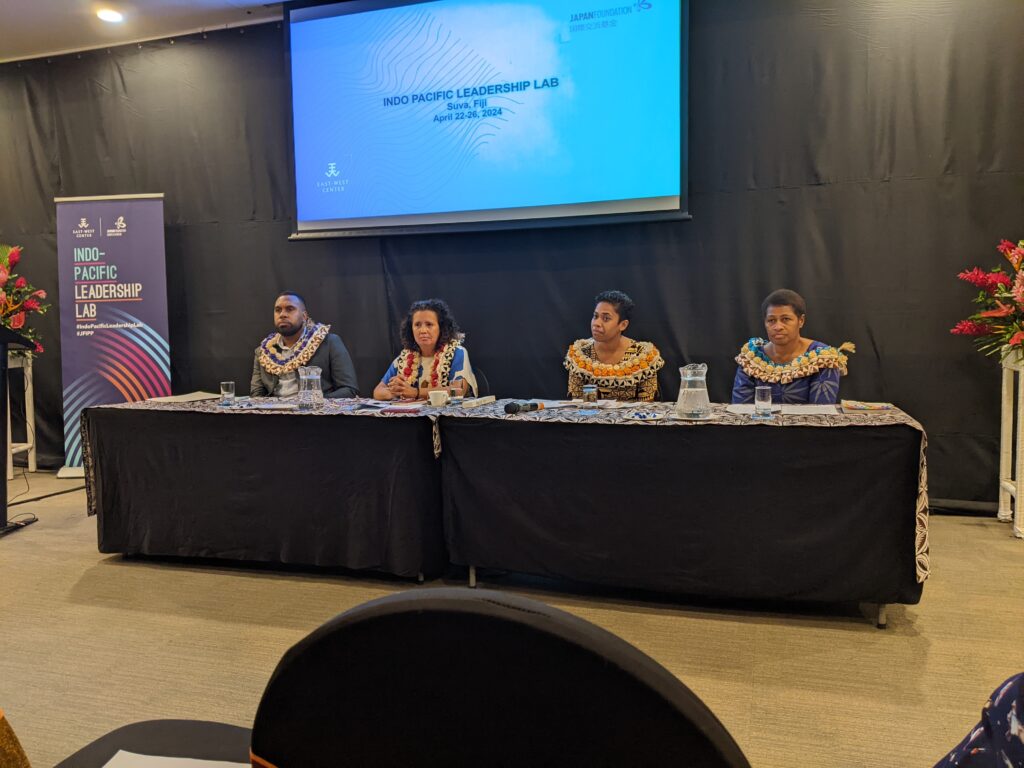

The Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab [5] is a program of the East-West Center,[6] with support from the Japan Foundation.[7]

As always, content on this blog reflects my personal views, and not those of any organization with which I am associated.

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/climate-lab-planning-for-change/

[3] https://radicalmoderate.online/climate-lab-diversity-inclusivity-and-equity/

[4] https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137011435_10

[5] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/projects/indo-pacific-leadership-lab

[6] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/

0 Comments