Part 3

“Ki”

Miyazaki’s heroines have been described as projecting their inner harmony outward into a damaged world. [1] In writing this series (and even in making my San costume for Halloween), I’ve had a lot of opportunity to think about the role I play in this world and what outcomes I want to support with my own actions. So much of how that manifests itself – aside from my day job – is through this blog (which is somehow approaching its sixth anniversary). Because writing is so important to me, I frequently explore various aspects of writing techniques, especially how to do it more effectively. As long-time readers will know, one of the biggest lessons I took from my Climate Lab [2] over the last year is the value of storytelling in conveying information.

Image credit: [3]

The human race has been telling stories for 150,000 years, and our brains have evolved to engage with the data in stories in a way that we still can’t engage with pure data alone. The stories we share and how we share them fundamentally shape how we view and engage with the world around us, which is why effective storytelling is such a vital tool in challenging and polarizing times. Interestingly and unsurprisingly (as is the case with any tool), how we wield it can make things better or worse. That is why we will wrap up this series on Miyazaki’s movies with a look at the story structure itself and why – in addition to his strong female characters and his more nuanced approach to complex subject matter – the stories themselves feel different (as well as why that’s important).

“Sho”

In the western world, particularly when it comes to Hollywood movies, we’re used to a three-act structure in our stories: setup, conflict, resolution. Although I was a theatre kid and familiar with the general arc of stage productions, I first heard about this concept explicitly in an interview with George Lucas at the beginning of my “Star Wars” VHS set. Lucas described the original trilogy as a play in three acts: “in the first act you introduce everybody; the second act you put them in the worst possible position they can ever get into in their lives, and they’re in a black hole, never able to get out; and in the third act they get out.” [4]

That structure, based on Joseph Campbell’s concept of “The Hero’s Journey,” forms the basis for the vast majority of the stories (particularly the movies) we consume: the hero goes on a journey, faces an obstacle, and comes home transformed. [5] It’s predictable; it’s simple; it’s conclusive. It’s comforting in its familiarity and its moral absolutism. (It’s why Christian and I watched “Lord of the Rings” so often during 2020.) But it’s also fundamentally different than what we get from Miyazaki because his stories follow a (literally) foreign narrative structure.

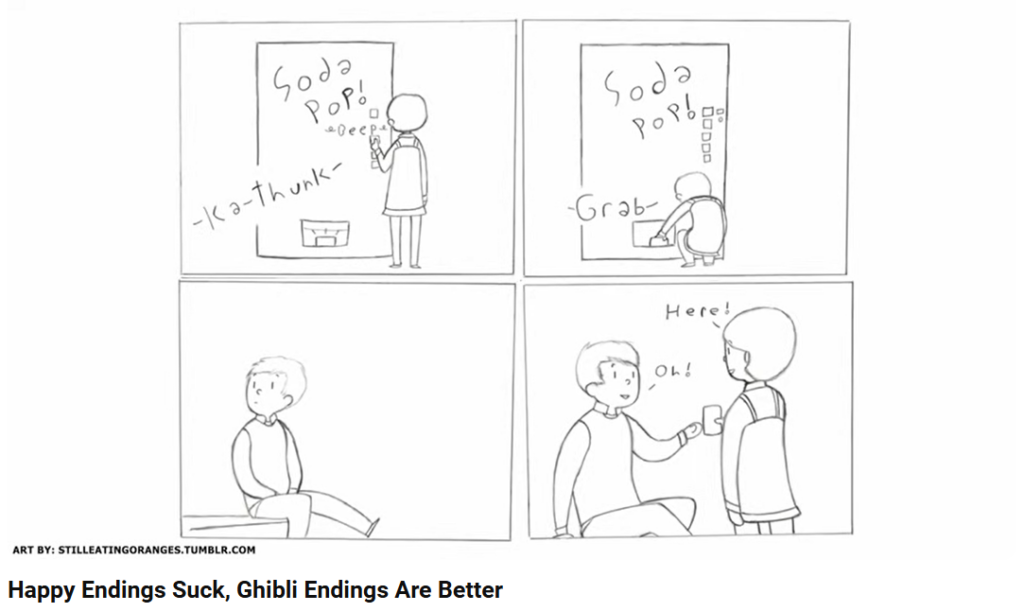

Image credit: [6]

“Kishotenketsu,” as it is called in Japan, is a storytelling tradition from ancient China that spread throughout the region and lives on today in the movies of Studio Ghibli. Instead of using three acts to depict a conflict, this form uses four acts to depict a change. Act one, or “ki,” introduces the characters / situation; two, “sho,” provides development; “ten” introduces a twist or tension, which can be seemingly unrelated to what came before; and “ketsu” demonstrates the outcome / results from that twist. Without a major conflict driving the plot, these movies can feel unsatisfying to some viewers because they lack the finality and narrative conclusiveness to which we’ve become accustomed. [7]

But for other viewers, it can feel much more realistic because it doesn’t wrap everything up with a perfect bow at the end: it leaves unanswered questions and parts of the story open to interpretation; it provides a lot more space for character development and depth (as we covered in Part 1 of this series [8]), as well as for ambiguity and exploration of contradictions (covered in Part 2 [9]). In short, while a three-act, conflict-driven narrative allows audiences to be intellectually passive, a four-act, change-driven narrative invites us to think.

“Ten”

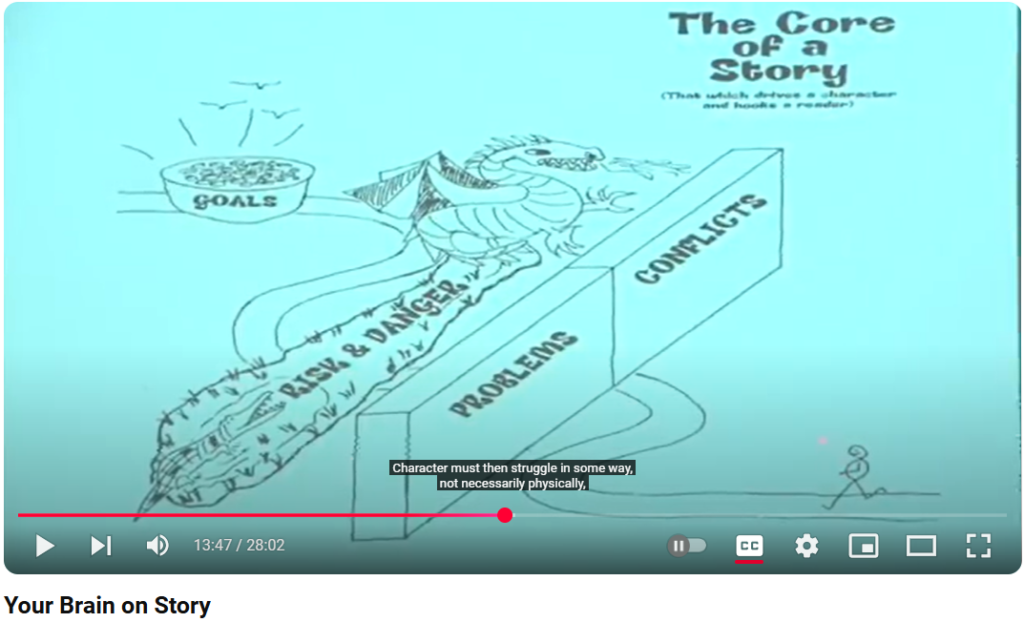

But here’s where it gets interesting. The human brain absorbs and retains data to the extent we can make logical sense of it in story form. Because of how our brains have evolved to function, they will actually distort information we receive (ignoring, augmenting, even reversing pieces of what we hear) in order to assemble it into a cohesive narrative. A Department of Defense study examining how humans respond to story demonstrated that humans naturally anticipate a story arc in which a protagonist overcomes problems and conflicts, facing risk and danger in the process, in order to reach a goal. Because that is the expected story structure, we will simply start putting data wherever it needs to go to fill in the gaps. [10]

Brené Brown de-escalates emotional triggers that arise out of ambiguous situations with the phrase “the story I’m telling myself is…” [11] with the understanding that our brains are doing the best they can to make sense of whatever they receive. She understands that it is a highly imperfect and highly personal process that makes our brains jump to whatever conclusions they can find in order to fit seemingly disparate pieces of information into a clearer picture. And if the picture we expect to see is informed only by our standard three-act, conflict-driven, good-vs-evil narrative structure, we will be far more likely to create a story for ourselves that fits that mold – a story with polarization, moral certainty, and in which good guys must win and bad guys must lose.

Image credit: [12]

What that all means is that data does not – and cannot – ever speak for itself. As a storyteller, if you do not quickly provide a story to make sense of the data (and even sometimes if you do) your audience will fill in the blanks themselves and may arrive at conclusions you don’t want. That lesson is one of my biggest struggles professionally, especially coming from a science background and assuming everyone else will share my perspective when it comes to available data. That is why telling a story effectively is not simply providing relevant content but organizing it in a meaningful way, with a clear understanding of what you want to convey and with whom your audience is likely to identify.

“Ketsu”

About a year ago when I watched a TED talk on strong storytelling in leadership [13] (along with a couple other YouTube videos in that particular rabbit hole), I fundamentally changed how I presented information to audiences both at my job and on this blog. I would begin pieces I was writing by answering the three questions “what’s the context?”, “what’s the conflict?”, and “what’s the outcome?”, thus creating my own little three-act play. (Long-time readers should easily be able to recognize it in the format of most of my 2024 blog posts.) It’s a strong and useful approach to storytelling, particularly when it’s critical to demonstrate a clear problem-action-solution progression. However, it can’t be the only option for us, especially in situations that are complex and evolving, which represents most of what we encounter in our daily lives.

Learning about Miyazaki’s use of kishotenketsu while working on my Halloween costume, I was reminded of a marketing workshop I attended at an energy conference almost a decade ago. We learned “the three words that are guaranteed to make your writing better”: “but,” “therefore,” and “meanwhile.” [14] This trio is not a direct corollary to kishotenketsu (and it can be used effectively in the three-act format too [15]), but it allows for more narrative complexity, parallel structure, and open-ended storytelling. You can find it throughout investigative journalism (particularly on NPR) if you look. (And it influenced the structure of the blog posts in this series – let me know if you noticed a difference!)

Image credit: [16]

I’m not saying the three-act, conflict-driven arc is always bad and kishotenketsu is always good – there are roles for each. What is worth considering is that the kishotenketsu arc provides a much more realistic mirror to our lives. The truth of our world is that we’re not in a zero-sum game on a finite timeline: we live in a world of nuance and complexity, and while “good/bad” rhetoric is great for getting humans to give you their attention and energy, it’s less effective for arriving at meaningful long-term solutions.

The ends of Miyazaki’s movies often find us seemingly back at square one, but with personal growth and new knowledge on the part of the protagonist(s). That’s not a bad thing; it’s a realistic thing – and I think it’s a good thing for us to consider difficult times with more of a Miyazaki-esque perspective: not with an eye toward winning or losing but toward making progress, even if only in our tiny spheres of influence.

Thank you for reading!

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QCUKgF3aOsQ

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/tag/climate-lab/

[3] https://www.followthemoonrabbit.com/studio-ghibli-storytelling/

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l0BxWKZpkzg

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hero%27s_journey

[6] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qf-oLlAPDsc

[7] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qf-oLlAPDsc

[8] https://radicalmoderate.online/the-world-of-miyazaki-strong-women/

[9] https://radicalmoderate.online/the-world-of-miyazaki-paradoxes/

[10] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zGrf0LGn6Y4

[11] https://youtu.be/5RsPjFnNdw4

[12] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zGrf0LGn6Y4

[13] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJfGby1C3C4

[14] https://www.vox.com/2015/4/1/8327255/writing-advice-tips

[15] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1GXv2C7vwX0

[16] https://tedlassogif.tumblr.com/post/677268438126854144

0 Comments