In honor of Halloween (thinking of zombies, vampires, and all of the horror movie monsters that just will not go away), this post is appropriately focused on plastics. Plastics are a ubiquitous evil in our society that are here to stay, whether we realize it or not. Our plastic clothes degrade in the washing machine, putting microplastics into our waterways; our plastic waste goes into landfills where it will sit for possibly centuries;[1] our plastic litter (including cigarette butts, drinking straws, and plastic bags) makes its way into waterways, harming marine wildlife.

Our society has become unbelievably dependent on plastics, particularly single-use plastics, and particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. The plastics lobby has fought hard to maintain the perception that we need single-use plastics for safety purposes in the pandemic,[2] despite the fact that fomite transmission (surface transmission) of SARS-CoV-2 is a lower risk for spreading the virus, especially when good hand hygiene is practiced.[3] But that’s another topic for another time.

Perceptions Persist

Because of the prevalence of plastic in everything we purchase, the result is a massive amount of plastic waste. The United States in particular was at the top of total numbers (42 million metric tons in all) and per capita numbers (130kg, or 286 lbs, per person) in 2016, according to National Geographic.[4] And the sad news is that far less of it gets recycled than we think.

Over the past few years, I’ve had conversations with a number of friends explaining that just because you say something is recyclable, that does not mean that it gets recycled. This unfortunate fact is especially true with plastics because they are so difficult to recycle. The ubiquitous “chasing arrows” icon indicating that something can be recycled was, in fact, developed by the plastics industry to increase use. Several big names in oil production and plastics manufacturing were behind the push for branding all plastics as recyclable,[5] and the common misperception that recycling is a “get out of jail free” card has lagged.

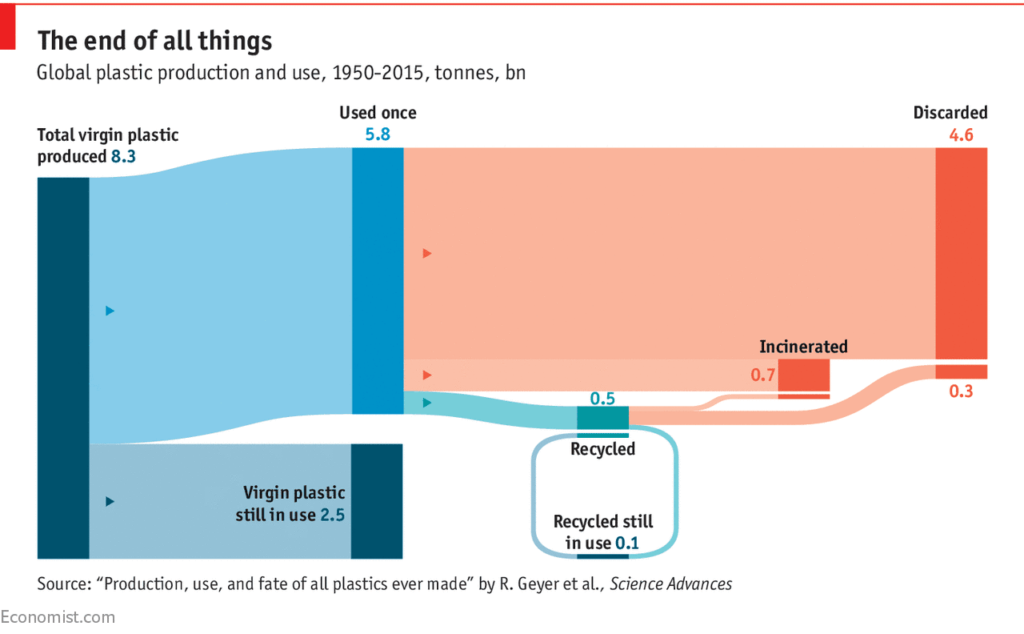

In fact, the opposite has happened. The planet is inundated with plastic waste because only about 9% of the world’s plastic gets recycled. Part of the problem is that it is difficult or expensive to recycle certain types of plastic, and consequently, much of it is landfilled or incinerated. Since it is so cheap to make new plastic, it is often more cost effective to trash existing materials rather than recycle them. Furthermore, as I learned almost three years ago (a revelation that helped to launch this blog), only certain types of plastic are recycled in most communities, including Pittsburgh. Fontline aired a fantastic summary of the problem with their “Plastic Wars” documentary last year.[7]

Plastic recycling for much of Pittsburgh and the surrounding communities is limited to #1 and #2 plastic bottles, jars, and jugs,[8] which are made from a slightly different plastic and cannot be recycled together with other #1 items. A former colleague who once ran a materials recovery facility (MRF) described the process to me and said that anything that fell outside the category of what was actually recycled was landfilled or incinerated.

He told me that the reason most municipalities opt for single-stream recycling (where everything potentially “recyclable” is collected in a mixed bin) is to make it easier for consumers. The more complex the process, he said, the less likely people are to participate. However, single-stream leads to consumers being less aware (which frequently means throwing everything in, whether it’s recyclable or not), and recyclers having much more work to do when sorting what comes in. While sorting machines are becoming much more sophisticated, it’s no substitute for education on the part of consumers.[9]

Recycling Options (or Lack Thereof)

Plastics are expensive to recycle, and the time it takes to sort them is often not cost effective, especially when virgin plastic is so cheap. For years the United States sent much of our plastic to China, where it was sorted by low-wage laborers. After China stopped taking it in 2018, we began to face a reckoning around what happens with that much waste, particularly when we can’t recycle it and other countries won’t take it.

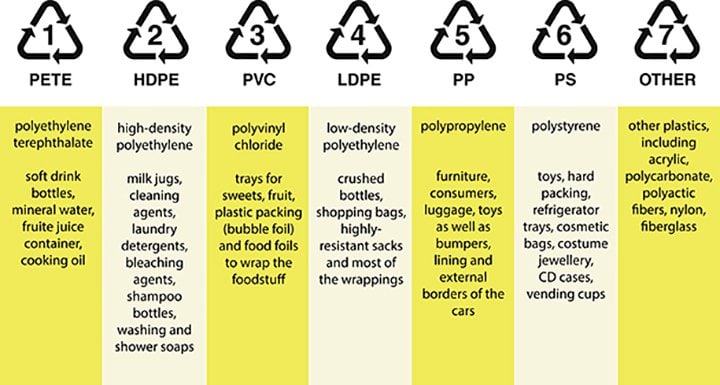

Plastics come in a variety of types, and they are grouped into categories based on their properties.[11] Some are far easier to recycle than others, which is why some programs are more common than others. #1 and #2 are the most commonly recycled plastic and are the extent of what most municipal recycling programs collect – and even then they likely have additional restrictions. #4 and #5 plastic recycling programs are rarer and are usually run through progressive grocery stores or recycling companies. I personally have never seen a program that recycles #3, #6, or #7.

I have been sorting our glass, cardboard, aluminum, and steel for almost three years now, since I learned how inefficient and inaccurate the curbside collection process can be. Fortunately, we live a few miles away from a recycler that takes all of these materials, so I make regular trips to drop off our recyclables. During that time, only #1 and #2 plastic bottles were going in our curbside collection. I recently heard that this company had started taking plastics. All plastics. Naturally, that claim was met with some skepticism on my part, particularly when their advertisement said that plastics #2 through #7 could be comingled.

As part of my research on this subject, I had a conversation with Boyd Jones at Michael Brothers Hauling and Recycling,[12] who was willing to talk to me about what they accept and why. He explained that they have some buyers that take all #1 plastic, regardless of shape. Everything I have ever heard on this subject says that all types of #1 cannot be commingled for recycling because they are fundamentally different plastics. This new information, including their buyer and what they do with the waste, definitely warrants further investigation.

Recycling vs. Repurposing

Regarding the rest of the plastic collection, Boyd explained that Michael Brothers recently found a buyer who wanted all plastics #2 through #7 as feedstock for a product they create: porous planks that are used for landscaping applications, such as French drains, green roofs, and retaining wall drainage. The ones on display at Michael Brothers’ Baldwin location were reminiscent of plastic funnel cake. Apparently this product was created through support from Dow, which raised my curiosity even more.

The company is called HydroBlox,[13] and their website says the product is recycled, which is a misnomer. Recycling implies that you are taking a given material (say, #5 plastic) and turning it back into the same material (#5 plastic). Noted in the plastic lifecycle image above, true closed-loop recycling is difficult and rare. Much of what we call recycling is actually something called “downcycling,” a process in which recyclable materials are made into lower quality products over time as the materials degrade. For example, the material requirements for a yogurt container are much more exacting than the material requirements for a park bench or a landscaping block.[14]

Downcycling, while not ideal, is not entirely bad either. It often means that some virgin resources can be spared in place of a repurposed material. (I touched on this a little bit in my asphalt shingle recycling research earlier this year.[15]) I do not know enough about the HydroBlox product at this point to give it a definitive yea or nay because I still have some questions, specifically…

- what impact does this product have on the addition of microplastics into waterways?

- what is the useful life of this product?

- what happens at the end of this product’s life? e.g. Is it landfilled or can it be melted down to create new planks?

I am glad that there appears to be a market for our hard-to-recycle plastics that can divert them from a landfill, at least for a while. I am always in favor of reducing demand for virgin plastics. For those reasons, I am glad that this option is available to residents in the area.

I do, however, want to stress (as I always do on this blog) that “the Three Rs” (reduce, reuse, recycle) are meant to be done in that order. Recycling – or something called recycling – is not a cure-all and cannot be looked to as a solution, but rather as a last resort. Reducing our dependence on plastic is essential: buying less in the first place and avoiding single use plastics whenever possible.

As with any good research project, I am coming out of this post with more questions than I started. I encourage you to stay curious and ask questions when you have them. I hope I will have more to share on this topic in the future.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://chariotenergy.com/blog/how-long-until-plastic-decomposes/

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-06-08/is-plastic-the-coronavirus-hero-the-plastics-industry-thinks-so

[3] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/surface-transmission.html

[4] https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/us-plastic-pollution

[5] https://www.npr.org/2020/09/11/897692090/how-big-oil-misled-the-public-into-believing-plastic-would-be-recycled

[6] https://learn.eartheasy.com/articles/plastics-by-the-numbers/

[7] https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/film/plastic-wars/

[8] https://recyclethispgh.com/item/what-plastics-can-go-in-pgh-curbside-recycling/

[9] https://www.npr.org/2015/03/31/396319000/with-single-stream-recycling-convenience-comes-at-a-cost

[10] https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2018/03/06/only-9-of-the-worlds-plastic-is-recycled

[11] https://www.greenmatters.com/renewables/2018/09/13/ZG59GA/plastic-recycling-numbers-resin-codes

[12] https://michaelbrothershauling.com/about

[13] https://www.hydroblox.com/

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Downcycling

[15] https://radicalmoderate.online/my-cabin-doesnt-leak-when-it-doesnt-rain-part-3/

0 Comments