Part 3 – Where Power Resides

This post follows from last week’s look at why we appear to have become so politically polarized as a country. Part of it is individual perception and the fact that our regular diet of news from social media (which is tailored to each individual) insulates us from dissenting opinions while simultaneously feeding us stories from specific sources, limiting our view of the whole picture and further entrenching us in our own opinions.[1] The other part is, I believe, the reality that in allowing more centralized power in the executive office, our democracy becomes more of a winner-take-all system, which makes each subsequent presidential election all the more crucial – and heated.

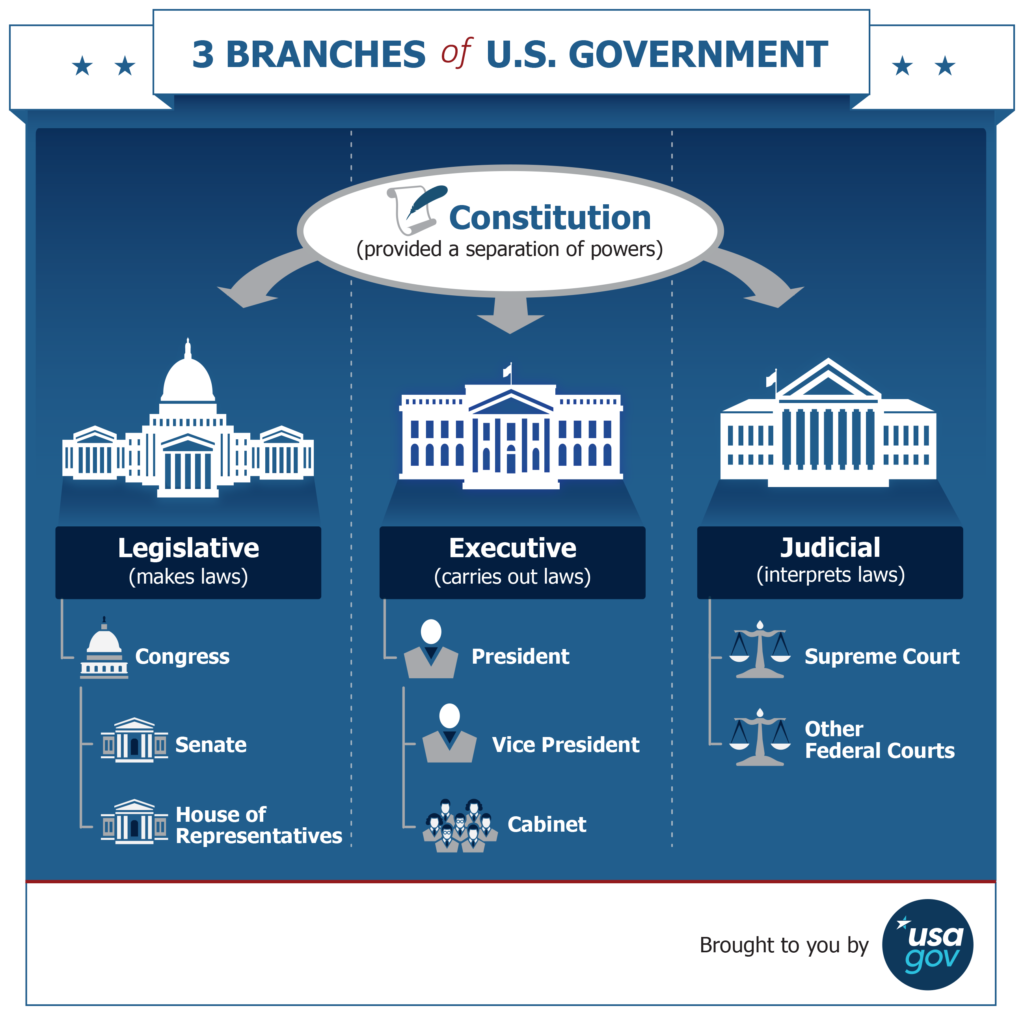

Given the way our government was constructed to have checks and balances between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, I have always found it curious how many voters put so much stock in the presidential election and pay little attention to anything else, particularly down-ballot races and elections held in the intervening four years, which impact local and/or state issues. I am consistently surprised at how few people know who their representatives are and at the even smaller number of people who have actually reached out to them to express their opinions. Yes, it takes more work to do the research and contact your local elected officials on issues that matter to you (believe me – I know), but it also helps to ensure proper representation.

I’ll add a disclaimer that I’ve only been been what I would call “involved” in politics for the better part of one decade, by which I mean actively participating in research on issues and subsequent outreach by email, phone, and office visits to my elected officials. I have not spent a lifetime studying the history of our government and the interplay of our parties, so I admit to limited perspective here. (If you are a student of history and/or political science, I would love to hear your thoughts below!)

Image credit: [2]

Centralized Power

That being said, to my eyes, there appears to be a correlation, if not more causative relationship, between our increased focus on the presidential seat and the control we allow that office to have. In part 1 of this series I mentioned the general shift right in our economic policies, but also the general shift upwards from small-government libertarianism to large-government authoritarianism.[3] This week as many people across the country are already receiving mail-in ballots and filling in bubbles, we’re going to look at the consolidation of power in the executive office.

You may remember from civics class that the US government has three branches: the legislative (congress), which makes laws; the executive (president), which carries out laws; and the judicial (supreme court), which interprets laws.[4] I try to stress every year during election season how absolutely crucial down-ballot races are. The president sets the overall tone for the country during the four to eight years he is in office and has power over government agencies, but it is the legislature that makes the laws. Putting all of our attention on the office of the president is dangerous and enables a more authoritarian system, no matter who sits in the White House. It also leads to more severe pendulum swings as the party in power shifts.

It could be argued that we have seen significantly more power consolidated in our executive branch in the past few years, which I would guess may be some combination of perception and reality. Certainly over the last two decades, responses to terrorism, economic recession, and disease outbreaks have called for a more coordinated approach at the top, meaning more control and more spending. When the president has the backing of both chambers of congress (which has happened for at least two years with every president since Clinton), his power is supported and, understandably, magnified.[5] In the case of a divided government, the president’s goals may be harder to achieve without the backing of both the House and the Senate (such was the case with Reagan and Bush Sr.), but there is another tool available: the executive order.

Image credit: [6]

Executive Orders

The executive order is not law, but rather a directive that manages operations of the federal government. It is subject to judicial review and may be overturned by the Supreme Court if it is deemed unconstitutional. Nonetheless, it can be incredibly powerful: among famous executive orders are Teddy Roosevelt’s creation of national forests and Franklin Roosevelt’s internment of Japanese-Americans.[7] In 2001, conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation, raised concerns about Clinton’s use of the measure, quoting the US Constitution, the Federalist Papers, and French philosopher Montesquieu on the importance of the separation of powers.[8]

“There can be no liberty where the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person.”

– Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu

Our current president is a fan of the executive order, having issued 187 as of the writing of this post.[9] And while he certainly doesn’t come close to the record (FDR had 3,522 during his 12 years in office), he has been issuing 10 to 15 more on average per year than his most recent three predecessors, and has in four years issued more than our first 15 presidents combined. It is interesting to note that Trump’s average of 46.5 per year is more in the ballpark of Bush Sr. (41.5 per year) and Reagan (47.6 per year), who both dealt with a divided government for all 12 years of their combined terms.[10]

Court Seats

One other power the president has that is of great importance to the function of the government is the nomination of judges – not just in the Supreme Court, but in appellate and district courts as well.[11] The senate has had a Republican majority since 2015, at which point it effectively delayed confirmation of judges nominated by Obama, allowing Trump to take office with 88 district court vacancies, 17 appellate court vacancies, and one Supreme Court vacancy, all of which were quickly filled.[12] At this point, the confirmation hearing of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Supreme Court replacement will likely take place before the election. [Note: At the time this post went live, the senate would remain at home until October 19 after a COVID-19 outbreak among high-ranking members of the GOP, narrowing the potential window for a confirmation hearing before Election Day.]

Image credit: [13]

There has been what seems to be additional fervor surrounding Supreme Court nominations over the past four years, more than I remember in prior presidencies, but I fully admit that may be a matter of perception. According to Pete Buttigieg, “every single time there is a vacancy, we have this apocalyptic ideological firefight over what to do next,” so I would trust that this issue is not a new one.[14] While the role of the judicial branch is to interpret – not create – law, we tend to see a presidential litmus test relating to interpretation, i.e. which laws will be interpreted in what way, most notably relating to Bill of Rights issues and Roe v. Wade.

In doing research, I was intrigued to find that the Supreme Court used to be a lot more partisan and a lot less powerful. Nineteenth century Americans were more concerned with the power that resided in the court than they were with its level of partisanship. In the early 20th century, the court’s powers grew, and simultaneously so did concerns about it being a political entity – the idea being that if the court were apolitical, it would be trustworthy.[15] I would venture a guess that a balanced court may appear from the outside to be non-partisan, but that it is not, nor can it be when justices are hand-picked based on their political leanings. That raises my concerns as well if the powers of the court have grown along with the dubious assumption of non-partisanship.

There are some suggestions on the table for how to better handle the periodic fight over filling these all-important empty seats, such as expanding the bench or enacting term limits, but this is not a problem that will be solved in the next month.[16]

~

As we go into the next month, it is important to remember that there are forces at play actively trying to divide us – and benefiting from that discord. Empathy is a tool I will be calling on frequently, reminding myself that as much as I have learned, there is always more to uncover. Over the coming month especially, when I disagree with someone, I will seek to understand the reason behind it, to learn what the other person’s hopes and fears are. So to start, I would ask that you let me know what you think – especially if you disagree with anything I’ve said here.

Click here for information on my (and maybe your) ballot races:

Thanks for reading.

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/november-2020-elections-part-2/

[2] https://www.usa.gov/branches-of-government

[3] https://radicalmoderate.online/november-2020-elections-part-1/

[4] https://www.usa.gov/branches-of-government#item-214495

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divided_government_in_the_United_States

[6] https://www.britannica.com/topic/federalism

[7] https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/faculty-articles/249/

[8] https://web.archive.org/web/20081019235518/http://www.heritage.org/Research/LegalIssues/LM2.cfm

[9] https://www.federalregister.gov/presidential-documents/executive-orders

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Executive_order

[11] https://www.uscourts.gov/judges-judgeships/authorized-judgeships/judgeship-appointments-president

[12] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2018/06/04/senate-obstructionism-handed-judicial-vacancies-to-trump/

[13] https://medium.com/thatrosschap/a-tribute-to-friendship-and-decency-a529b1877456

[14] https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/votervital/should-we-restructure-the-supreme-court/

[15] https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/supreme-court-politics-history/2020/09/25/b9fefcee-fe7f-11ea-9ceb-061d646d9c67_story.html

[16] https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/votervital/should-we-restructure-the-supreme-court/

0 Comments