Part 3 – Transmission and Testing

Because we’ve had so much uncertainty around the novel coronavirus (how many people show symptoms, how easily it’s transmitted, and even what the long-term health impacts are), I have erred on the side of caution wherever possible, much to the exasperation of some friends and family members. But I also know how irresponsible and guilty I would feel if I had contributed to the spread of the virus, and that I could never forgive myself if I did anything to damage my parents’ health.

Again in this post, I will be mentioning my job, which is executive director of a public health organization. This post represents my own views, not the organization’s. I am not a medical expert, and any scientific findings I share reference the appropriate source.

Transmission and Impacts

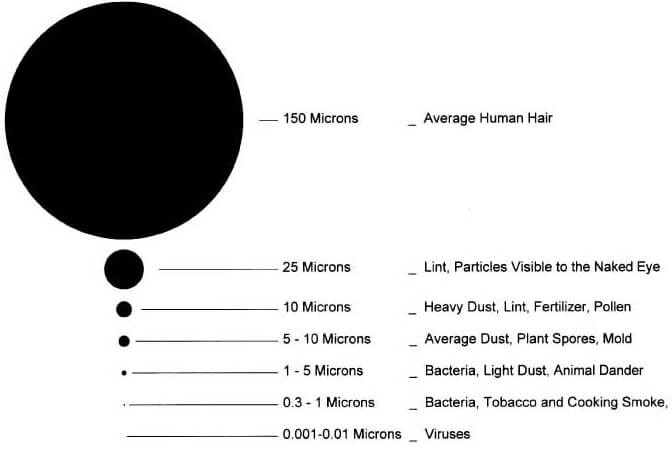

Guidance is evolving as we learn more about the virus. According to the World Health Organization (at least as of July 9, 2020), it appears that infected people can transmit the virus through saliva and respiratory droplets (5-10 microns in diameter), “which are expelled when an infected person coughs, sneezes, talks or sings.” At some point this summer, I remember hearing news that scientists believed the virus could also be airborne, spreading through transmission of “aerosols” (microscopic droplets smaller than 5 microns) in certain settings, which can pose a risk when combined with droplet transmission in crowded indoor spaces, such as “choir practice, in restaurants, or in fitness classes.” Infected surfaces have not been ruled out, but it is difficult to study that type of transmission in isolation from droplets and aerosols.

With respect to who could be transmitting the virus, “SARS-CoV-2 transmission appears to mainly be spread via droplets and close contact with infected symptomatic cases,” but “early data from China suggested that people without symptoms [either positive cases who never develop symptoms or positive cases before they develop symptoms] could infect others.” Therefore, the best mode of action to prevent transmission is “identifying suspect cases as quickly as possible, testing, and isolating infectious cases.”

Image credit: [1]

Unfortunately, widespread testing is still not an option in the United States, so the best way to prevent the spread is to assume anyone could have it and take necessary precautions. Again, the WHO says “given that infected people without symptoms can transmit the virus, it is also prudent to encourage the use of fabric face masks in public places where there is community transmission and where other prevention measures, such as physical distancing, are not possible. Fabric masks, if made and worn properly, can serve as a barrier to droplets expelled from the wearer into the air and environment. However, masks must be used as part of a comprehensive package of preventive measures, which includes frequent hand hygiene, physical distancing when possible, respiratory etiquette, environmental cleaning and disinfection. Recommended precautions also include avoiding indoor crowded gatherings as much as possible, in particular when physical distancing is not feasible, and ensuring good environmental ventilation in any closed setting.” (Emphasis mine) [2]

While the main focus of the COVID-19 conversation seems to have been around mortality rate (whether or not it will kill you), we are beginning to see the possibility of lasting health impacts of the virus as people recover, or don’t. Common symptoms that can linger over time are fatigue, cough, shortness of breath, headache, and joint pain, but more severe, permanent organ damage is a possibility as well, including:

- lasting damage to the heart muscle, increasing the risk of heart failure or other complications;

- long-standing damage to the tiny air sacs in the lungs, with scar tissue that can lead to long-term breathing problems;

- brain damage that can cause strokes, seizures, and a condition that causes temporary paralysis; also indicated is an increased risk of developing Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s;

- blood clots and blood vessel problems, which can affect the lungs, legs, liver, and kidneys, as well as causing heart attacks and strokes. [3]

I am lucky to be young, healthy, and at low risk for the disease – but the same cannot be said for my family. For months I said that I wasn’t afraid of contracting COVID-19 myself, but I was afraid of passing it to others. With emerging information about permanent damage to the lungs, heart, and brain, I’m starting to worry about myself as well. I find so much joy in singing and running, for example, that I can’t even imagine not being able to do those things anymore.

Test Availability

I had been trying to get home to visit my parents since March, when my mom started a round of chemo treatments. I wanted nothing more than to help with shopping, chores, and keep her company while she was going through a difficult time. Of course, my dad was with her, but he’s got health issues of his own, and I didn’t want either of them having to go out and put themselves at risk. However, with so much still unknown about asymptomatic transmission, I didn’t want to risk unknowingly passing something to them myself.

Image credit: [4]

Unfortunately anywhere I called to schedule a test said that only people with symptoms could get an appointment. The alternative was to quarantine fully for two weeks – Christian and I would have to stay in completely, with no grocery shopping, no food delivery, and no going into work. Although Christian was willing to take Paid Time Off to do that for me, I still had to go to the office once a week to meet with our accountant and sign checks (as I was still in the process of hiring someone who could deputize for me in my absence.)

Around the end of July, I started to feel a little sick. At first I thought I was under-hydrated after a long day of gardening, but the headache, muscle aches, chills, nausea, and sore throat persisted for several days. Upon mentioning it to Christian, he noted that he had had a headache and muscle aches a few days before mine started. We had only been to the store and to work; we had both been so careful for so long. It was incredibly frustrating.

The upside was that if this had to happen, the timing could not have been better: I had just gotten my new deputy director added to our bank account at work, so I could isolate myself at home without negatively impacting our business operations. Plus, I could finally get a test scheduled, as I was exhibiting symptoms. I knew there was a delay in 1) getting the test, and 2) getting the results, so I also knew I needed to be careful while waiting it out.

In-Home Isolation

Considering the possibility that I might just have a cold and not COVID-19, I was well-aware that this could be my chance to finally see my parents. Given that, I didn’t want to risk contracting it between when I scheduled the test and when I got the result (especially since Christian was still going into the office), so we began social distancing in our own house.

Citizen science at its best: demonstrating mask effectiveness with flammable aerosols

Image credit: [5]

We researched CDC guidelines on what to do if you suspect someone at home has it, and that includes (to the greatest extent possible) sleeping in separate bedrooms, using separate bathrooms, wearing masks if you must be in the same room, and frequently washing your hands and disinfecting surfaces.[6] Some friends of mine have waited up to two weeks for test results, so I emotionally prepared myself for the long haul. (After two weeks of isolation, they may as well have just quarantined instead of getting a test – and if given the option again, I will opt for the quarantine.)

My doctor’s office has a drive-thru testing tent set up outside: pull up, confirm your identity, sign the paperwork, and get the test, during which a nurse sticks a flexible plastic swab up each nostril, far beyond the point of comfort, and twists it on the way out. The test itself has been described as “unpleasant,” and I would say that is a gross understatement. If a trip to see my parents weren’t on the line, I wouldn’t have even let her swab the second nostril. I was able to hold my head still and breathe steadily through my mouth as instructed, but I reflexively coughed in the her face during the second swab and apologized profusely. It seems that is not an uncommon reaction: she said that’s why she was wearing a face shield.

Amazingly, one day later, the doctor called me back with my results: negative. I packed some clothes, my laptop, and my cat, and headed east to see my parents for the first time in over 5 months, and that is where I have been writing this entire series.

~

Next week I’ll wrap up the conversation (for now) with my own reflections about various responses to the virus and my own political crisis of faith.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://www.pickcomfort.com/water-quality/micron-rating/

[2] https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/transmission-of-sars-cov-2-implications-for-infection-prevention-precautions

[3] https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/coronavirus-long-term-effects/art-20490351

[4] https://www.kob.com/albuquerque-news/covid-19-doctor-explains-how-the-nasal-swab-procedure-works-/5678373/

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x6cTDGqcUpA

[6] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/if-you-are-sick/care-for-someone.html#face-covering

0 Comments