Part 2 – Where We Live

Last week I mentioned that individual action and political action are valuable components of fighting climate change, but those things are not enough. Building operation is a huge, largely untapped area of opportunity for energy savings in our country. While our minds tend to go straight to rooftop solar when we think of sustainability-related improvements for buildings, the most impactful steps you can take for a building involve using less energy, rather than changing your fuel source.

I spend my days in energy efficiency, specifically working to improve building performance (and associated health issues for occupants). While I may have some biases because of my day job and the industry in which I operate, everything I say here is based on fact and presented as objectively as possible.

Again, I feel the need to put a disclaimer on here to say that I am sharing this information independently of my relationship with Conservation Consultants Inc.[1] My opinions are my own, and I am mentioning my employer only because of the insight I have gained through my job and how that relates to this topic.

Building a Better Way

Buildings in the United States account for about 40 percent of energy used in our country.[3] The total energy used to light, heat, cool, and power the buildings in which we live and work now surpasses the total energy used by all countries in the world other than China and our own. According to the US Energy Information Administration, the world average of per capita energy consumption in 2016 was 78 million Btu (British thermal units); the per capita average for the US alone in 2018 was 309 million Btu, almost four times the global average.[4]

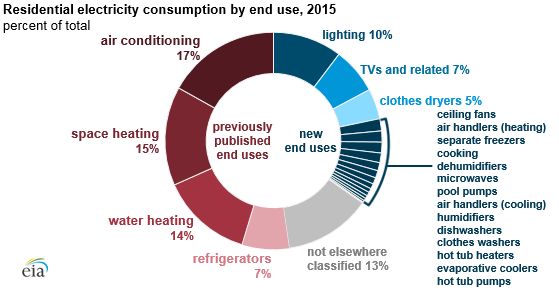

I used to work at a for-profit company doing energy efficiency calculations for commercial spaces, but that was several years ago, and that work was largely – but not exclusively – related to lighting retrofits (i.e. swapping older, less-efficient lighting for newer, energy-saving alternatives). While lighting can be a significant portion of energy savings, it is far from the only thing that can be done to improve a building’s performance. Lighting is usually the first thing to be addressed because of the comparably low capital cost and significantly quick return on investment. I will write more about the commercial sector next week, but for this post I want to focus on something a little closer to home.

I now work in the residential sector, and my non-profit organization has a lot of irons in the fire. We do political advocacy, helping elected officials understand the positive impact of energy efficiency; we partner with other organizations to promote best practices in the industry and align resources to create a more strategic process in improving homes; we serve private homeowners by examining opportunities for saving energy and giving them a road map should they choose to move forward with our recommendations; and we run outreach and education programs in neighborhoods that need the most assistance.

Barriers to Success

Slightly more than half of that 40% of building energy use comes from residential buildings,[6] and individual action on the part of homeowners is in some ways more achievable than it is on the commercial side… but in some ways not. As a homeowner, I can simply decide to caulk around my windows if they’re drafty or put insulated foam board on my attic hatch to keep warm air from escaping in the winter. But – and this is a big one – I can only do that if I know what to do and if I can afford to do it. There are huge barriers to energy efficiency on the residential side, and many of them prevent us from improving our housing stock, thereby using less energy, and thereby helping the environment:

- Every home is different. Different age, different layout, different building materials, and different occupant behaviors all contribute to the layered complexity of assessing opportunities for energy efficiency and with developing solutions. There is no one-size-fits all method when it comes to saving energy, and even if there were…

- Every homeowner is different. It is important to remember that not everyone has the same level of familiarity with the impacts of energy efficiency on climate or even the same priorities. Education usually starts at or near square one with many homeowners, and as soon as you move on to the next home, that education process starts over again.

- Health and efficiency are tied together. Houses are not perfect and can easily contain toxins that are hard to find, such as lead paint, radon, mold, and asbestos. Sealing up your home to save energy can make things worse for your health if you aren’t careful. Efficiency improvements need to be done mindfully, but many homeowners (and many contractors) don’t make that connection.

- Building codes may not be current and/or not properly enforced. Because of code adoption procedures at the state level, we typically see a four-year lag in adopting new codes in Pennsylvania.[7] However, these codes apply to new or significantly-renovated homes, not to existing homes – and that results in a growing gap between new and existing buildings. Additionally, just because a building meets code does not mean it is energy efficient. My coworkers have assessed plenty of atrocious newly-constructed homes that could do with thousands to tens of thousands of dollars of work simply to bring them up to what is considered average efficiency for the US.

- Energy efficiency involves upfront cost. This barrier is a huge one. While you will save money in the long run by weatherizing your home, you may not be able to afford the initial cost of an energy audit (which is a crucial first step so you know what specifically your house needs and what health-related problems to take into account), and you may not be able to afford the energy-saving measures themselves.

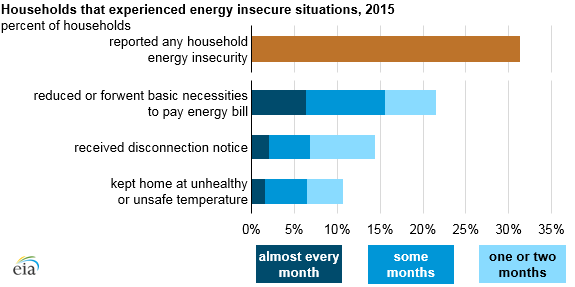

We see this issue a lot in Pittsburgh. We have some of the oldest housing stock in the country (ranked eighth for oldest homes, I heard at a conference recently), meaning many homes are inefficient at best; in disrepair and actively triggering health problems at worst. We also have the sixth-highest energy burden in the country, meaning that our residents pay, on average, 4.5% of their income on energy bills; our low-income families pay on average 9.4%.[8]

As part of my job, I interact with many of these families, and I know that it is hard to even broach this subject. If parents are working multiple jobs to put food on the table – and having to choose between electricity, food, and medical care – they don’t necessarily have the bandwidth to hear about energy audits and weatherization, even if those things can save them money down the road by reducing their energy bills and possibly even their medical bills.[9] (Pittsburgh neighborhoods have very high asthma rates, often triggered by the presence of mold in homes.)

It’s All Connected

It’s easy for me to swing from environmental justice to social justice when I talk about energy efficiency, especially in homes, because my work directly impacts both on a daily basis. The program I run provides no-cost services to low-income homes, and I am very proud of the impact we’ve had in multiple Pittsburgh neighborhoods. For a small set of homes, we have performed deep weatherization and health measures, helping them reduce their energy usage by close to 25%. For a larger set of homes in these neighborhoods, we have provided tools and support over the course of a year to help them weatherize their homes on their own and adjust their behaviors. The participants in that part of the program were able to reduce their energy usage by around 15%, and exit surveys indicated that participants felt that their homes were healthier and more efficient after taking part in the program.

If you would like to see more detail about the “Grassroots Green Homes” program, you can check out chapter two of the white paper that my organization published in fall 2017 after we completed the pilot round.[11] You can also check out the program’s YouTube channel for a set of instructional videos that cover all the tools and tips that were provided over the course of the program year.[12]

It is not my intention to use this post to brag about my own work, but rather to demonstrate the various impacts of energy efficiency in the home. Energy efficiency supports a healthy economy and job growth (90,000 jobs and growing in PA), individual health and financial well-being (limiting emergency room visits and lowering energy bills), and environmental health (using fewer resources, particularly fossil fuels, to power our buildings). The cheapest, cleanest kilowatt hour is the one that isn’t used, and while I fully support the development of renewable energy technology, I believe that energy efficiency – using less energy in the first place – should be the first step.

If I were to provide advice on something significant that you as an individual could do that goes beyond steps like eating less meat and riding a bike, it is this: take a look at opportunities to improve the efficiency of your house. Get an energy efficiency assessment if you can afford it or look into low-income weatherization programs if you can’t. Weatherize your home – whether you bring in a contractor to blow insulation or grab a caulking tube and some window plastic for simpler, cheaper do-it-yourself measures.

And tune in next week when we talk about commercial buildings – and how you might be able to sway your organization to make energy efficiency a priority.

Have you done any weatherization work in your home? Have you run into barriers that have prevented you from doing something you want to do? Share your story below.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://www.getenergysmarter.org

[2] https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/index.php

[3] https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=86&t=1

[4] https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=85&t=1

[5] https://getenergysmarter.org/community-projects

[6] http://www.c2es.org/technology/overview/buildings

[7] https://paeeconference.org/sessions/breakout-session-energy-efficiency-for-the-climate/

[8] http://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/publications/researchreports/u1602.pdf

[9] http://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/publications/researchreports/h1801.pdf

[10] https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/index.php

[11] https://getenergysmarter.org/sites/default/files/CCI%20Case%20for%20Healthier%20Homes%20-%20Final.pdf

[12] https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCTaiWD98b_Wp_VpJJaY9QlQ

0 Comments