Part 2 – Growing Food

In last week’s post we talked about the idea that buying local is the best way to help the environment.[1] The United Nations even recommends it as a way to lower your carbon footprint.[2] There are definite benefits of buying local, and we will cover those in this series, but lowering the transportation footprint of your food is not the biggest-impact decision you can make.

Life Cycle Analysis

Examining the total impact of any product involves a deep look into all of the resources used in production, transportation, use, and disposal. It is a complex process that involves a lot of data and/or assumptions. When I was in grad school, we had access to an incredibly sophisticated (and I’m sure incredibly expensive) Life Cycle Analysis software that would really come in handy for this blog. (Santa, if you’re reading this post, you know what to bring me for Christmas!)

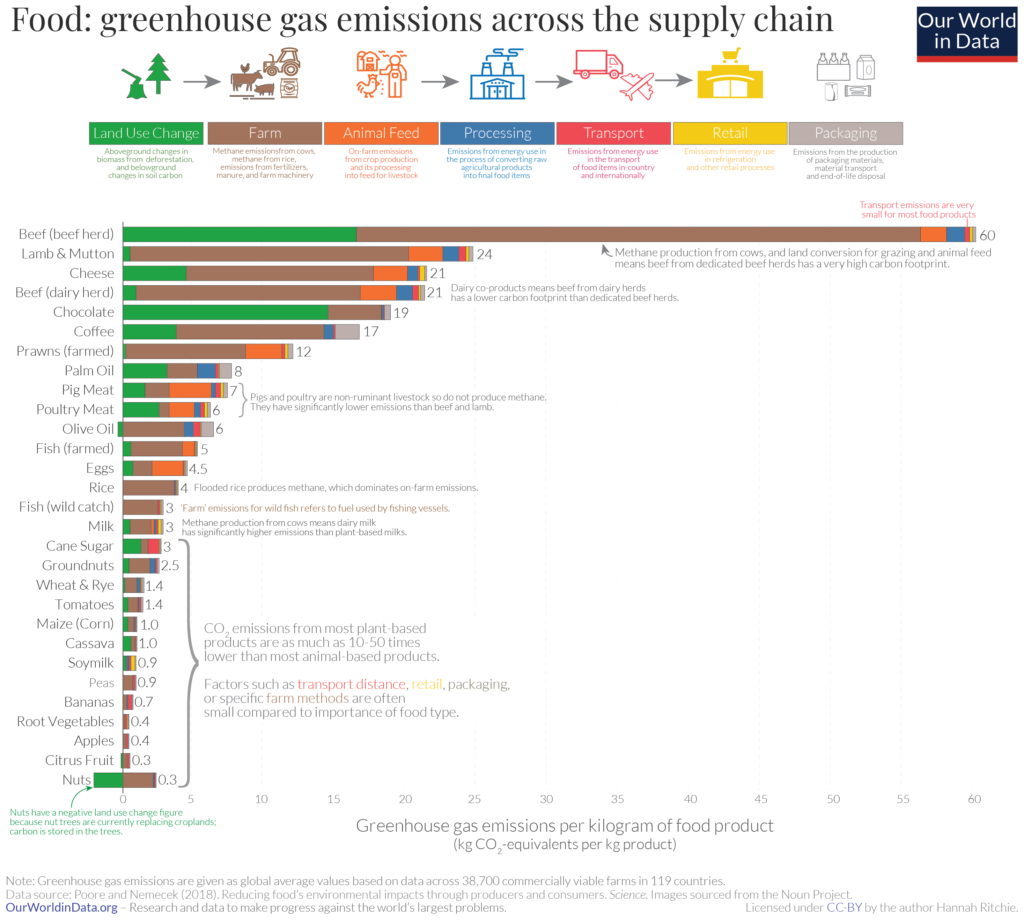

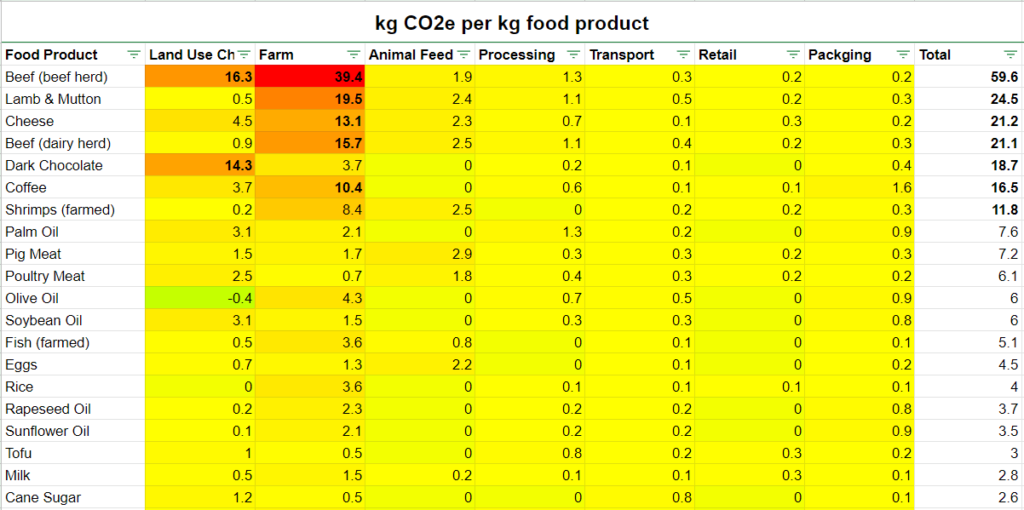

Organizations with access to vast quantities of data to analyze on this subject can look at several stages of food production and their individual impacts. The website Our World in Data [3] specifically examines the following…

- Land Use Change: aboveground changes in biomass from deforestation, and belowground changes in soil carbon

- Farm: methane emissions from cows, rice, etc.; emissions from fertilizers, manure, and farm machinery

- Animal Feed: on-farm emissions from crop production and its processing into feed for livestock

- Processing: emissions from energy use in the process of converting raw agricultural products into final food items

- Transport: emissions from energy use in the transport of food items in-country and internationally

- Retail: emissions from energy use in refrigeration and other retail processes

- Packaging: emissions from the production of packaging materials, material transport, and end-of-life disposal

Data in each of these areas come from a comprehensive study of 38,700 commercially viable farms in 119 countries, which examines food-miles, water footprint, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by food type.[4] The greenhouse gas units are measured in equivalent kilograms of carbon dioxide, or “CO2e” for each kilogram of food produced. Since different GHGs (e.g. methane, nitrogen oxides, etc.) have different impacts than carbon dioxide, listing them as an equivalent amount of CO2 provides an apples-to-apples comparison.

Image credit: [5]

Land Use Footprint

We’ll start off with by looking at Land Use Change. Clearing land for cattle to graze or for crops to grow can represent a huge environmental impact, as we see in Amazonian countries where “cattle ranching is the largest driver of deforestation, … accounting for 80 percent of current deforestation rates.”[6]

The biggest land use culprits we see in this food study are beef herds and chocolate, which are really off in a category of their own. (Before you chocolate fiends despair too much, keep in mind that these numbers are normalized by mass of food product, and that eating a quarter pound of beef is very different from eating a quarter pound of chocolate.)

As for the rest, all of the animal products are in the top half of the list, but there are some plant products up there as well, including coffee, palm oil, soybean oil, cane sugar, and tofu. Interestingly, we also see some items with negative land use GHG emissions, specifically those that involve trees (citrus, olives, and nuts) and vines (grapes), which absorb and store carbon.

Farming Footprint

Methane Emissions

This category is the real heavy-hitter on the list and represents more than twice the GHG impact of land use where beef cattle are concerned. Ruminant animals (e.g. cows, sheep, and goats) have chambered stomachs that allow them to process low-nutrient plant matter, such as grass. This biological feature also allows them to produce delicious milks and cheeses.

Unfortunately, ruminants create a large amount of methane. Methane is an extremely powerful greenhouse gas, 25 times more potent than CO2 in the long term (and far worse in the short term). Because of this biological feature, ruminant meats and cheeses are high on the list for carbon footprint. (You could elect to eat non-ruminant cheese, but horse milk is harder to come by and apparently not as tasty.)

It is interesting to note that there are plant materials on the list that create methane of their own, such as rice. Methane is emitted by flooded rice fields, but the total GHGs per kg of rice during farming is still only 10% that of beef. Most of the items that come in my CSA (e.g. apples, onions/leeks, potatoes, vegetables, root vegetables) are all grouped together at the bottom of the list, along with soy milk and barley (for beer!)

Data source: [7]

Farming Equipment

The reason most of these fruits and vegetables have any farming GHGs associated with them at all comes from the agricultural processes used to grow and harvest them. First, any gas-powered farm equipment will result in GHG emissions as a result of combustion. (Any human or animal labor used to till fields or harvest has an impact too, but we’ll stick to machine-powered farming for now.)

In my series on Roundup last year, I mentioned the unpopular argument that organic farming generally requires more tilling, and therefore the use of more fossil fuels to prepare the land. Roundup’s argument is that their product allows for less tilling and is therefore better for the environment, but that’s a debate for another time.[8]

Organic vs. Conventional

Interestingly, a recent Canadian study showed conventional and organic products coming out about neck and neck with respect to GHG emissions. Organic beef had slightly lower GHGs by weight than conventional beef, and conventional vegetables won out slightly over organic. There were several factors on each side that led to this conclusion.

Conventional agriculture uses synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, which take more energy to produce than organic fertilizers. However, organic fertilizers “tend to cause the release of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas, offsetting the lower emissions from energy use in organic production.”[9]

If GHGs are your concern, splitting hairs between organic and synthetic fertilizers should not be where you focus your attention. Just from looking at the data from land use, farming, and transportation over the last two posts, we can see that what you choose to eat has significantly more of an impact than how far it travels or whether it’s organic. Some analyses indicate that “going ‘red meat and dairy free’ (not totally meat-free) one day per week would achieve the same as having a diet with zero food miles.”[10]

While ingredients are clearly the most important factor in GHG footprint, next week we’ll look into some of the other categories to better understand some of the supply chain impacts, including preservation out of season and packaging. Until then, here’s another recipe to get you through the mountains of vegetables in your CSA subscription…

Generic and Out-of-the Ordinary: Recipe

I love soup because you can put pretty much any CSA veggies in it, but even I can only eat so much of it. I also desperately miss Chinese food, but I haven’t been ordering any lately because of the plastic packaging. Here is a recipe that solves both problems: it can use any number of vegetables that arrive on a regular basis, while also shifting the flavor palate eastward.

This recipe is heavily modified from what I found on food blog The Forked Spoon.[11] I’ve made it a couple times now and appreciate the flexibility it offers.

Bok Choy and Tofu

Ingredients:

- 1 Tbs canola oil

- 1 Tbs fresh ginger, grated or minced

- 3 cloves garlic

- 2 Tbs sesame oil

- 6 Tbs soy sauce

- 1 Tbs rice vinegar

- 4 Tbs honey or brown sugar (I skipped this)

- 2 tsp water

- 2 tsp corn starch

- a few spoonfuls of roasted chilies (depending on your spice preference)

- 4 cups bok choy (or other vegetables), chopped

- 14 oz firm tofu, cubed

Sautee the ginger and garlic in the canola oil for a minute, then add sesame oil, soy sauce, rice vinegar, and honey/brown sugar (if you’re using it). Stir until combined, then add water and corn starch. Stir until smooth, then add vegetables. Stir until veggies are soft, then add tofu and stir until it is coated.

Serve over steamed rice.

~

Can you cut out red meat and dairy for one day? I plan to go vegan one day per week, and I’ll let you know how it goes.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/community-supported-agriculture-part-1/

[2] https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/feeding-world-sustainably

[3] https://ourworldindata.org/

[4] https://ourworldindata.org/food-choice-vs-eating-local

[5] https://ourworldindata.org/uploads/2020/02/Environmental-impact-of-food-by-life-cycle-stage-768×690.png

[6] https://www.ecowatch.com/seasonal-and-local-food-2615393675.html

[7] https://ourworldindata.org/uploads/2020/02/GHG-emissions-by-life-cycle-stage-OurWorldinData-upload.csv

[8] https://radicalmoderate.online/roundup-and-glyphosate-part-4/

[9] https://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/local-organic-carbon-footprint-1.4389910

[10] https://ourworldindata.org/food-choice-vs-eating-local

[11] https://theforkedspoon.com/spicy-stir-fried-tofu-with-bok-choy/

1 Comment

“Examining the total impact of any product involves a deep look into all of the resources used in production, transportation, use, and disposal” – The Bethlehem Gadfly · December 4, 2020 at 2:01 pm

[…] Community Supported Agriculture, Part 2 […]