<– Start at the beginning of the Climate Lab series

Working in public health and being personally concerned with climate change, I understand – conceptually – that the issues I’m trying to comprehend and address are complex. However, we humans have a tendency to reduce complexity and create certainty out of complex and uncertain situations. [1] We do it for comfort, if not self preservation, and I can absolutely attest to how easy and comforting it is to slide into a world of my own making where there are simple good/bad, right/wrong labels to apply to people and their actions, and where I can quickly feel better about myself and the choices I make.

It is such an incredibly seductive situation, and I have recently noticed that the more anxious I get about the state of the world, the more I spend my limited, precious time watching YouTube videos in which comedians make fun of the foibles and missteps of various political figures. Is spending my time that way a distraction from the things that are producing stress? No. … a simplification of them? Yes. … a useful way to spend my time? Absolutely not – because these situations are anything but simple, and believing that they are (and believing that my limited perspective is the “correct” one) is utterly counterproductive to what I am trying to achieve in my work, both personally and professionally.

“Simplify, Simplify, Simplify”

In my Climate Lab sessions, we had spent time looking at ways leaders effectively deal with complex situations – defined as situations in which changing one thing changes other things too (intentionally or unintentionally). [2] Appropriate leadership skills and organizational approaches for situations like that are critical, and so is having an informed understanding of the different interrelated factors to be addressed in those situations. Unfortunately, humans are fundamentally incapable of having the level of omniscience required for properly addressing complex situations, even if we’re actively trying to work against our tendency to simplify for the sake of our own comfort. That said, we do have some tools available to help us develop a greater level of awareness.

Image credit: [3]

I was disappointed that I didn’t have a dedicated class about Systems Thinking back in grad school. Apparently the cohorts immediately before and after mine both did, but mine only covered the subject briefly in the scope of a more general course (whose name I can’t even remember). The week or so my grad school cohort spent on the subject of Systems Thinking theory was fascinating, which was why I was so excited to hear we would have a dedicated session in my Climate Lab coursework. Once again, one 90-minute class is not enough to do justice to an entire field of study, but this time I’m in the position where I’m looking to apply my learning in the context of real-world scenarios, not just complete an assignment for a grade before moving onto the next thing.

At its core, Systems Thinking is a method for understanding how different factors are interrelated within a system and how they interact with each other to create different outcomes. When working to unpack a given issue, it can be incredibly easy to overlook factors that have exacerbated the problem and what unintended consequences may result from a given course of action. Applying systems thinking models helps us understand complex situations from the standpoint of how we got to where we are and how we can move forward as effectively and equitably as possible.

Fuzzy Logic

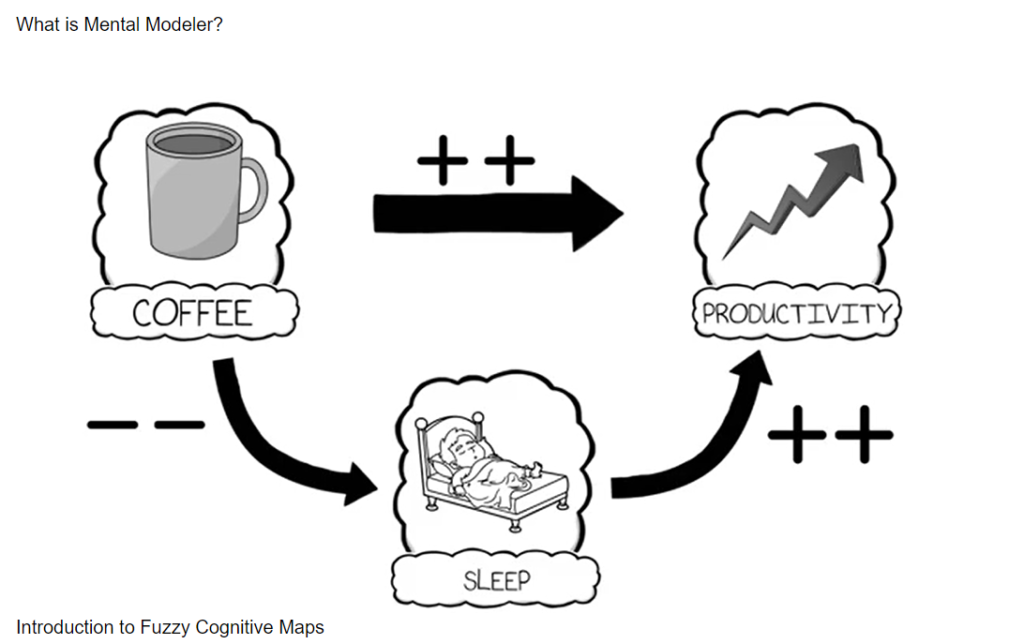

There are many different models and frameworks that can be used to support a system analysis, and they range from very data-heavy and analytical to very… not. Sitting somewhere in the middle of that spectrum is the Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping approach, which integrates aspects of qualitative and quantitative models. It is particularly useful in situations where there is high uncertainty and little empirical data, which is frequently the case in the field of public health.

The process of applying this model to a given issue (such as the example we used in class, which was the effect of climate-led displacement on mental health in Bangladesh) is to identify the components of a system (e.g. jobs, food availability, community ties, infrastructure, income, water availability, access to health care, and interpersonal relationships), and then determine how each of these components is related to the others. There may be positive relationships, such as an increase of jobs leading to an increase in income, or negative relationships, such as an increase in storm severity leading to a degradation in infrastructure quality.

Image credit: [4]

Each of those relationships, once identified, can then be weighted as having a low, medium, or high impact in order to better assess how the entire system might shift given a change in one component. Some cases may include a feedback loop, where individual components reinforce each other (such as limited job availability leading to people leaving a community, which leads to fewer businesses opening there, which leads to less job availability, and so on, resulting in a downward economic spiral). It should be noted that feedback loops don’t only consist of vicious circles: “virtuous circles” (upward spirals) also exist, and mapping these complex situations can help reveal ways to enable them.

Work Smarter, Not Harder

Identifying these components and relationships is fairly intuitive, and the more diverse the group, the more robust the model becomes as new perspectives and priorities are added. It should come as no surprise that these maps have the potential to become incredibly complex, with positive and negative impacts appearing across different relationships. When I was learning about these systems in grad school, my assignment involved a simple, hand-drawn map on notebook paper. Unsurprisingly, it was a mildly annoying situation to have to edit a completed map after coming to a new realization – not an impossible barrier, but enough to limit my desire to keep asking “what am I missing?”

In our Climate Lab session, I was very excited to learn about interactive online tools, such as MentalModeler, [5] which enable the creation of complex maps without destroying an entire eraser to constantly update a static pencil sketch. It may sound inconsequential, but lowering the barrier to add components and relationships to a map will help ensure that said map continues to evolve over time, becoming more useful in the process. But even more exciting than just creating the map in this tool is using it to run analyses of what you’ve created, with quantitative summaries of the various impacts resulting from a given change. This functionality makes “what if” scenarios incredibly easy (and dare I say fun?) to run.

It should go without saying that these models are tools, and the usefulness of the outputs is dependent on the quality of the inputs. As mentioned above, we humans don’t have perfect, objective information, and we often tend toward simplifying situations in favor of what makes us comfortable. It is incredibly important to recognize our incomplete knowledge and implicit biases – and then to address those limitations by increasing the diversity of perspectives and expertise we bring to the table. The earlier you can identify gaps in an approach, the better: it is far easier to shift things around in a model on a computer screen than it is in an entire department of people who have been hired based on an incorrect assessment of a situation.

The goal is not to fail, but to get comfortable with the idea of failing… because we’re human, and we will – and that’s how we improve.

Image credit: [6]

Real-World Applications

Of course, complete information is the ideal, but it’s important to remember that it’s not actually possible to achieve in reality. I recognize my own tendency to wait until something is perfect to reveal it to others (like many of these blog posts), but perfection is as time consuming as it is unachievable. As with the Fuzzy Cognitive Model, our approaches need to be as comprehensive as we can manage in the limited time frame available (which, for climate change, is short), but also flexible in order to incorporate new information as we go – and that information needs to come from stakeholders who may not necessarily agree with or even like each other.

Systems thinking relies on honest feedback from everyone impacted by a given decision, and sometimes just the act of building a model opens the door for conversations that were not previously happening. The people involved in the conversation don’t have to agree – in fact, the result will probably be stronger if they don’t. Stress-testing assumptions, raising alternate viewpoints, trying unconventional approaches, and learning from failures are all necessary components of successful innovation, uncomfortable as they may be to experience in the moment. And it’s also important to remember that as hard as you try to address a situation in a thoughtful, methodical, proactive, equitable manner, most likely everyone will be at least a little disappointed and lose out on something.

Looking back at my experience in grad school with a more seasoned and administrative perspective, I have to wonder if the decision to remove a dedicated Systems Thinking course from the class of 2011’s curriculum was an attempt to tweak the program based on feedback, but was ultimately deemed unsuccessful (hence why they brought it back the following year). If that was the case (and that’s a huge, speculative “if”), that piece of information resulting from trial and error benefitted the MBA program overall in future years, but it was based on a detriment experienced by my class. And given that thought, it’s a great reminder that progress isn’t linear, and long-term success is built on some short-term failures – or at the very least, long-term success is built on the recognition that improving the process as a whole requires prioritizing long-term successes over short-term successes.

~

I will leave it there for now, but I am excited to explore applications of these ideas in more detail in the context of our Climate Lab cohort’s in-person session in Fiji, so stay tuned for that…

Thank you for reading!

The Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab [7] is a program of the East-West Center, [8] with support from the Japan Foundation. [9]

As always, content on this blog reflects my personal views, and not those of any organization with which I am associated.

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/climate-lab-its-complicated/

[3] https://quotefancy.com/quote/1585074/George-E-P-Box-All-models-are-wrong-but-some-are-useful

[4] https://www.mentalmodeler.com/#resources

[5] https://www.mentalmodeler.com/

[6] https://www.jimmlasser.com/fail-harder-wall

[7] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/projects/indo-pacific-leadership-lab

[8] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/

0 Comments