<– Start at the beginning of the Climate Lab series

As we progressed into the final stretch of our year-long Climate Lab, members of our cohort were still wrestling with the concept of a final deliverable that showcased our learning but also served as a useful tool for others. My theory as to why we were having so much difficulty is because of how open-ended the assignment was. Many (if not all) of us have spent significant time in classrooms earning advanced degrees, in non-profit spaces delivering outputs for specific grants, and/or in government-adjacent roles demonstrating progress toward highly scrutinized initiatives. I don’t want to speak for everyone in the cohort, but in broad strokes, when someone is used to discrete, sequential, rubric-laden tasks, it can be very difficult to approach an initiative that has far less structure.

Image credit: [1]

I have loved being in the classroom my whole life: aside from my passion for learning new things, I have also found the order of the academic environment to be very comforting, with its hierarchy of expertise, objective grading system, and clear “right-and-wrong” ways to do things. (Of course I’m simplifying things here, as anyone in academia will tell you, but it’s to make a point.) Arriving at the stage in my career when it was my turn to make decisions based on incomplete information, with no clear “correct” path forward, was a challenge for me – and it still is. And my point is that whether we’re talking about intentionally ambiguous guidelines for an individual assignment or reaching a career phase that involves generating new knowledge, it’s that unknown next step that presents the challenge. And those examples serve as microcosms of the big one that we’re all dealing with, whether we know it or not: climate change.

Don’t Believe Everything You Think

In a recent blog series, I described how artificial intelligence is currently incapable of taking lessons from one area and applying them to another; it still needs humans to do that. [2] But just because humans have that ability doesn’t mean it’s easy – or that we always do it. If I fail to apply an obvious lesson effectively in a certain situation (e.g. “get community buy-in on a community-focused project”), I can see clearly after the fact why it failed, and that failure serves as an excellent teacher for next time – assuming there is a “next time.” Furthermore, getting it right “next time” still doesn’t help the people “this time.” And the Climate Lab sessions leading up to our third and final in-person session in Japan demonstrated that a significant obstacle to getting it right “this time” is an attachment to things we believe to be “correct.”

I was incredibly excited to return to Japan for the first time since the pandemic. I was also unequivocal when asked what I thought we should explore while we were there: Fukushima, including rebuilding efforts along the coast and how the public perception of nuclear has impacted availability of clean energy there and worldwide. Long-time readers of this blog know that Fukushima has a very special place in my heart. The eight-part blog series I wrote after visiting the Fukushima exclusion zone in January 2020 covered social, environmental, economic, and ethical considerations of our energy choices, and I included it as a writing sample in my Climate Lab application. [3] While our Climate Lab travels in Japan ultimately took us elsewhere, our pre-departure sessions were loaded with relevant readings and discussions on the subject – and revealed some concepts I hadn’t explored around a solution I considered to be obvious.

Image credit: [4]

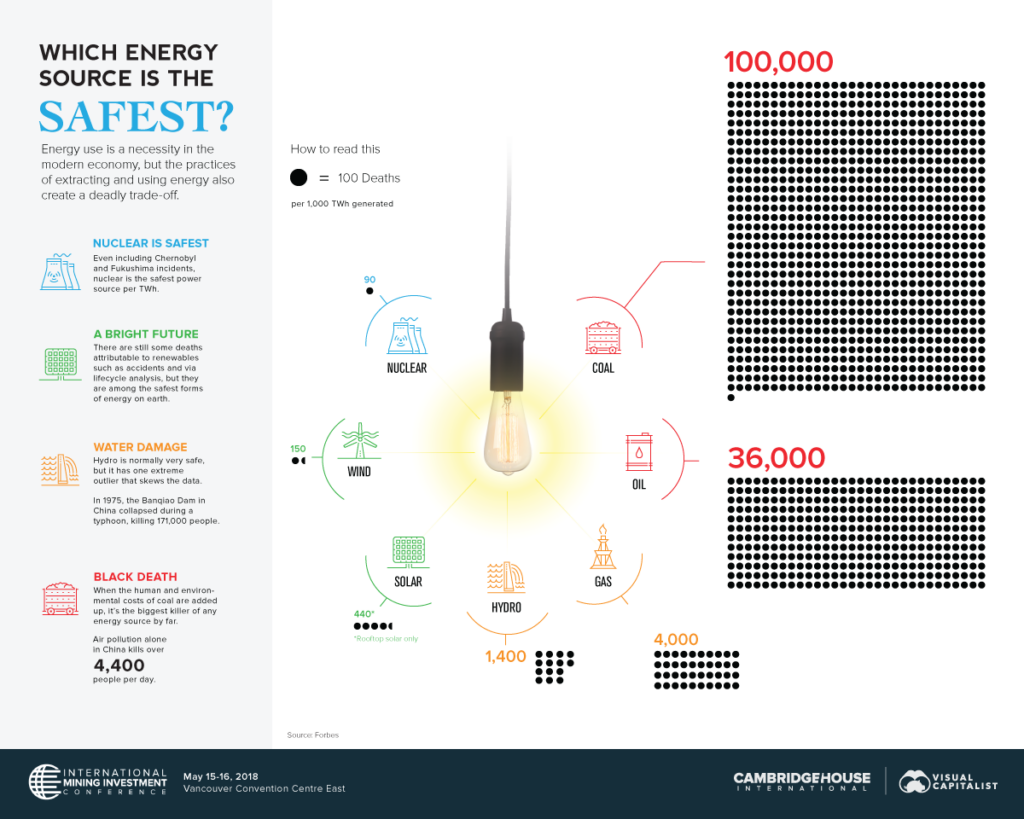

I regularly advocate for a “just transition to renewable energy” at my day job. The concept of ensuring effective social and economic support for communities that might otherwise experience adverse impacts from a transition away from a fossil fuel economy is described differently by the United Nations, [5] the US Department of Labor, [6] and basically any organization that provides a definition, [7] but the core sentiment is the same: ensuring that people who will be impacted will have a say in the decision. For me, personally, I believe that nuclear power has a significant role to play in this just transition to clean energy: it currently provides about 10% of the world’s electricity, and it is the safest [8] (or second-safest, depending on your calculations [9]) source of energy, based on number of deaths per Terawatt-hour produced (including modeled deaths from radiation exposure after Chernobyl and Fukushima). But if the transition is to be “just,” that means that potential host communities must have a say in hosting any type of energy infrastructure, even if it is the safest.

Vox Populi

My trip to Kahuku with the Climate Lab in January served as an excellent lesson in the importance of health equity in frontline communities even when the energy is renewable, [10] and that no form of energy generation is perfectly safe, even though some are far worse than others from a public health standpoint. In a world where energy demand is continually on the rise, it won’t be possible to eliminate health harms from energy generation altogether, but we can work to minimize as much harm as possible. Unfortunately, even that means that some harm will happen somewhere – likely in one place for the benefit of another, if history is any indication. In that situation, the question we should be examining is not what harm nuclear power (or any other power source, for that matter) causes, but who becomes expendable and why?

And that question meant I needed to check my own biases. For years I have argued that nuclear energy is the safest available; I have affirmed (when asked by a friend who was concerned about the technology) that I would have no qualms living next to a reactor. But imposing my perception of safety (grounded in statistics though it may be) on another community overrules the concept of just policy if it means leaving their concerns unaddressed. Fear is a huge motivator, and nuclear power is simultaneously one of the safest and one of the scariest sources of energy. The difference between reality and perception is key here: just the perception of disaster can result in chronic stress, which can contribute to other health problems. In short, a just solution involves more than simply deciding upon the safest form of energy generation and implementing it; it involves the much messier process of understanding and addressing the wide-ranging priorities and emotional responses of human beings.

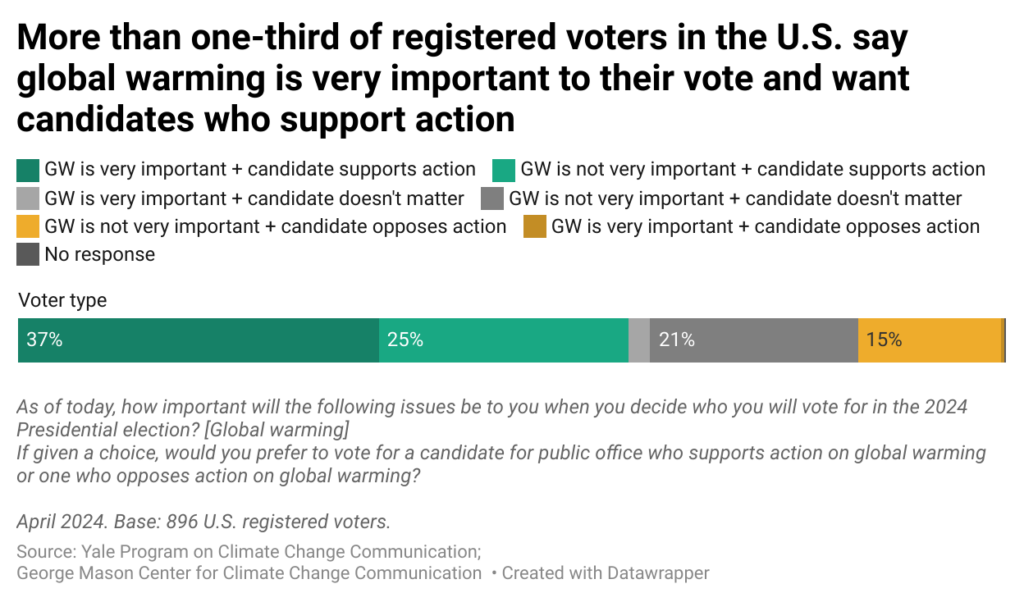

The power of human beings in large groups is incredible, often seen when common concerns that have been simmering for a long time bubble to the surface. We saw in the recent presidential election that common concerns – largely about economics, cost of living, and quality of life – drove a majority of Americans to vote for a candidate who (based on his own record and independent analyses of his proposed policies) will likely not alleviate those concerns. Humans, especially humans under stress, tend not to respond to crises with facts and logic but, rather, with perceptions and emotions. And I am beginning to believe that my own shortcomings as a leader stem from my propensity to operate with facts and logic and assume that anyone else will agree with me if presented with the same argument. (I also think that was a critical error on the part of the Democratic Party in the election.)

From the Ground Up

From years of community engagement work, I know (at least intellectually, if not intuitively) that successful efforts must start with correctly identifying and addressing the priorities of the residents. It is next to impossible to get someone to rearrange their priorities; if they feel they’re experiencing an existential threat, and you’re not speaking to it, you’re wasting your breath. That threat or concern may take any number of forms, and it is critical to remember that concerns like climate change (the existential threat of our time) could feel long-term and abstract to someone who sees making ends meet as an immediate, concrete priority. But, as I am fond of saying, these issues are not separate; in fact, they are often deeply intertwined.

Guest speakers to our bi-weekly sessions in the final months of the program described obstacles to broader climate action in the United States, Japan, and India. In some cases there were fossil fuel subsidies that couldn’t be removed because of the adverse impact on energy prices in low-income households; in others, there was the lure of good pay in the fossil fuel industry for workers with lower education levels. I’m painting with a broad brush again in order to make a point, but if many of the obstacles we are seeing in addressing climate change are economic in nature – and experienced at the household level – then it follows that we should be exploring options that alleviate those concerns, not simply looking at implementing top-down policy focused primarily on what fuel is used for generation.

Image credit: [11]

Don’t get me wrong: there is absolutely a need for ensuring significant emissions reductions across the globe, and we won’t get there without some sweeping, large-scale efforts. However, if the majority of American voters perceive strong climate policy as bad for their wallets (whether or not that is true), they will vote for someone who will limit climate efforts to the extent he can. What that means is that change will ultimately be driven by the people, for better or for worse. And the solution here cannot simply rely on educating people about a “right” or “wrong” choice – indeed, the “right vs. wrong” dichotomy actually shuts down our ability to evaluate complex, evolving situations. Instead, it must be a response to the immediate concerns of people who feel unseen, and it must not feel like they’re being asked to make a choice that is at odds with their interests.

~

In the coming posts, we will explore some of what those options might look like. But for now, I’d like to hear what you think – I shared a lot of opinions in this one and want to know where I made some incorrect assumptions.

Thank you for reading!

The Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab [12] is a program of the East-West Center, [13] with support from the Japan Foundation. [14]

As always, content on this blog reflects my personal views, and not those of any organization with which I am associated.

[1] https://mde.maryland.gov/programs/air/ClimateChange/MCCC/Pages/JTWG.aspx

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/man-vs-machine-ai-friend-or-foe/

[3] https://radicalmoderate.online/i-heart-fukushima-part-1/

[4] http://metals.visualcapitalist.com/safest-source-energy/

[5] https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/CDP-excerpt-2023-1.pdf

[6] https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/just-transition

[7] https://climatejusticealliance.org/just-transition/

[9] https://ourworldindata.org/safest-sources-of-energy

[10] https://radicalmoderate.online/climate-lab-hawaii-in-the-field/

[11] https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/understanding-pro-climate-voters/

[12] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/projects/indo-pacific-leadership-lab

0 Comments