<– Start at the beginning of the Climate Lab series

Climate Lab: Japan, Part 4 – Insights

Our experiences in the Climate Lab were eye-opening, whether during our virtual sessions learning about theory and practice, our in-person discussions learning from each other, or our time in the field learning from people who are feeling the impacts of climate change first-hand. Good travel, just like good education, puts you outside your comfort zone and helps you think about things from a different perspective (a central component of ecotourism. [1]) And the fact that I was able to have these experiences as part of a diverse group of leaders is why the three weeks we spent together on the ground in Hawai’i, Fiji, and Japan were so precious.

Bridge Between Nations

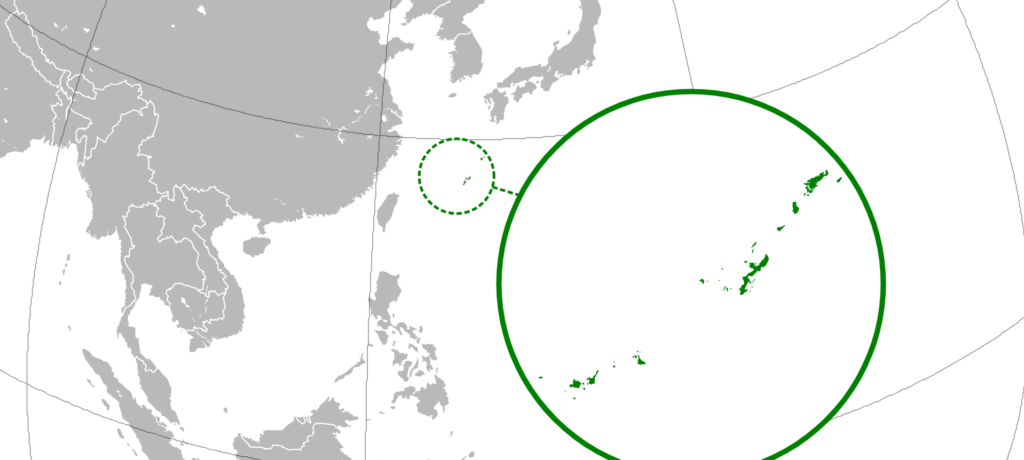

Ecotourism is the best word to describe some of our visits in these countries: at its core, it promotes a deeper sense of curiosity as well as an awareness of impacts associated with tourism, through the medium of cultural exchange and experiential learning, and ultimately encourages people to ask how they can contribute to a net positive wherever they go (which I try to keep among my goals when I travel). And when it comes to cultural exchange, I was surprised to see so much diversity in Okinawa, especially in contrast to what is still a very insular society on the Japanese mainland. The diversity wasn’t just apparent at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (where 80% of its nearly 300 PhD students are foreigners) [2] but in the general public as well.

Image modified: [3]

Okinawa’s largest industry is tourism, making up more than 80% of its economy, [4] and in order to support that industry, hospitality and entertainment companies need labor – preferably cheap labor. Consequently, there is a large immigrant population, which was approaching 27,000 in the summer of 2024, and is made up largely of those hailing from the US, China, Vietnam, and – curiously – Nepal. [5] Many of these workers live in low-income communities near the tourist destinations where they are employed, and those communities tend to see lower involvement with local activities, higher rates of welfare assistance, and greater need for childcare during off-hours. As a result, some community-based outreach organizations strive to provide support to these residents, who might not have access to other resources.

The municipal hall in the Wakasa neighborhood of Naha knows the value of a strong community network and hosts holiday parties and movie screenings so people can meet each other, skill building classes for first aid and disaster preparedness, and enrichment activities for kids (including a jazz orchestra) who need somewhere to go after school – all at no charge to its residents. Since there are often cultural, if not language, barriers in multinational communities, the Wakasa Kominkan tries to create events with a common goal that is relevant to multiple audiences. Speaking as someone who once felt very much like an outsider in Japan, language and culture classes provide a fun common ground with other foreigners, as well as useful skills and a connection to what is now home.

Cultural Evolution

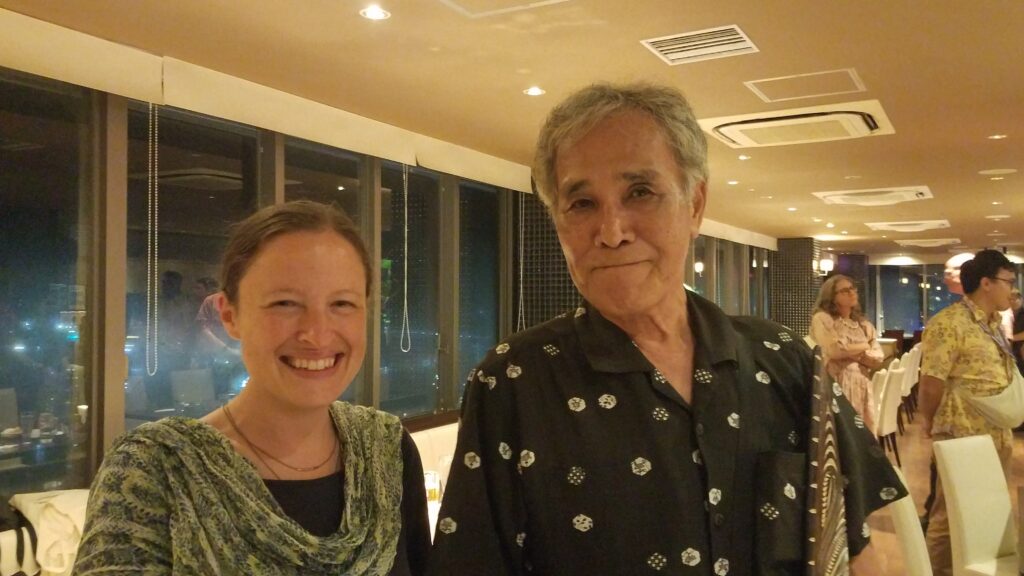

Okinawa is notably diverse compared to mainland Japan, which, again, felt like a very foreign concept in a country I thought I knew. (There are also many Okinawans who have emigrated throughout the world – at a notable rate, if conversations with residents are any indication. [6]) This former kingdom, for all the invasions, colonization, and devastation of war it has experienced over the years, is still very welcoming to foreigners… while also still very connected to its own heritage. Culturally it feels like those two attributes should be mutually exclusive, and we were curious as to why. We gained some insight into that question on our last night there, when we were hosted for dinner by former Vice Governor of the prefecture, Takara Kurayoshi. [7] Among his many accomplishments, he is a history professor and led the reconstruction of Okinawan landmark Shuri Castle after a fire in 2019. [8]

We rotated members of the cohort through his table in groups so everyone had a chance to speak with him. He was incredibly well-traveled and had a personal anecdote about pretty much everyone’s home country – he’s even been to Philadelphia. Over dinner, one of my classmates asked how Okinawan culture and traditions are still so present in a place with such high immigration, and whether native Okinawans are afraid of losing their culture over time in what is becoming more of a melting pot. Mr. Takara explained to us that there is an expectation of everyone who works in government there to study some kind of traditional Okinawan skill, presumably to preserve them but also to foster a common appreciation for them. He, himself, is a very talented singer and performed a folk song for us before the night was over.

Now, I have known plenty of first-generation Americans over the course of my life, and very often their parents are insistent that they learn the family’s language and culture, sometimes going so far as to enroll their kids in special classes on the weekends. The resulting tug of war is permeated by an intense fervor to preserve the culture (on the part of the parents) and sometimes a complete unwillingness to be involved (on the part of the kids), usually leaving both parties unhappy. I explained this situation and asked if there was the same dynamic in Okinawa. There was a little bit of a language barrier, so I wasn’t sure if his response represented the situation broadly or just his perspective, but he spoke about the importance of the younger generation learning about culture while also approaching it in their own way and making it their own.

Once again, I felt like the rug had been pulled out from under me. Having studied shamisen, dance, tea ceremony, aikido, and Japanese language when I lived up north, there was a very specific way to do something – there was no changing it or putting your own spin on it. I personally didn’t mind that rigidity too much (at least not at first) because I saw those art forms as perfect and unchanging, like something in a museum. But something I’ve learned in recent years as I’ve grappled with my own perfectionism is that perfect, unchanging things are dead. Latin is the quintessential example of a dead language: knowing it has its uses, but it is not generally spoken. English, on the other hand, is still evolving over time, which much chagrins the grammar sticklers among us but also allows room for shifts in culture, as well as creativity and innovation. (I think of Shakespeare, who invented some words and phrases we still use today.)

Yes, And…

My favorite example of a modern take on a traditional art form in Japan is the musical group Yoshida Kyodai (the Yoshida Brothers), who play a traditional style of shamisen popular in the north. They are exceptionally talented at performing traditional pieces but also write their own songs, inspired by rock, blues, jazz, and dance music. [9] Although I heard occasional protestations that their music wasn’t traditional or Japanese, their popularity indicates that those are not barriers to enjoying their music: when my friend and I saw them in concert almost 20 years ago, our age and nationality put us in the distinct minority among an audience full of kimono-clad Japanese grandmas. Exposure to a new take on a traditional art form can be a gateway into learning more about the art form itself (it was for me), but what I took from the conversation with Takara-sensei was that serving as a gateway doesn’t have to be its only value: that new form of expression can have value in its own right. And for as judgy as I can be about new things I don’t like or understand, I believe I get what he was saying.

Image credit: [10]

In school, I never enjoyed history class because it consisted of rote memorization of dates and names. In middle school, we learned about the Battle of Gettysburg [11] but also sewed Civil War uniforms in our home economics class and made wooden rifles in shop class before traveling to the battlefield and sleeping in canvas tents before reenacting Pickett’s Charge. As an adult, I’ve spent years participating in the Society for Creative Anachronism, [12] exploring aspects of life in the European middle ages by learning traditional skills and occasionally modifying the process for our modern world. In short, I have always needed something relatable if not fun to pull me into a subject – and anyone who has only known me as an adult would never believe that I haven’t always loved history.

From the perspective of science (my chosen field of study), participation is the point. You have to learn the basics, the history of the discoveries, etc. but then the end goal is to continue expanding and evolving the sum total of what we know about our world: you fill in a gap, you test an assumption, you corroborate a finding. Science doesn’t function without change, without people carrying it forward, but because the pace of scientific progress is slow, it can seem to be static for those who don’t understand the scientific method. [13] (And that slow pace can sow distrust of the scientific community in times of emerging issues, be it a global pandemic or a changing climate – but more on that later.) For now, my hypothesis is that for whatever subject of study you can name (including traditional cultural arts), you have to find a way to connect with it that is meaningful for you in order to enjoy it, and you have to enjoy it to do something meaningful with it. And to quote Shakespeare (via my AP English teacher), no profit grows where pleasure isn’t gained.

To wrap up this “bridge between blog posts,” I will share that this insight from the wonderful conversation I had with Takara-sensei is central to everything else I’m talking about here – and everything I do in my work (professional or otherwise). What resonated with me was the difference between commitment to keeping a beloved culture alive vs. attachment to specific, unchanging vestiges of a culture that become increasingly unrelatable over generations. Living things do change and evolve over time, whether we’re speaking literally about biological beings or figuratively about languages, cultures, or bodies of knowledge. And that awareness is critical when it comes to expanding perspectives: it isn’t about forcing someone to appreciate or believe something they don’t (like making a kid eat broccoli); it’s about finding a point of connection, something that the other person can appreciate or understand in the context of their own experience and working from there to build a bridge.

As a result of that approach, similar to what I said in my recent post on paradoxes, [14] what we see is not an opposition of conflicting sides where you can only pick one, but instead an expansion of perspective to include aspects of both. And we will cover more of that next week as I attempt to wrap up this series on the Climate Lab in Japan.

But for now, thank you for reading.

The Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab [15] is a program of the East-West Center, [16] with support from the Japan Foundation. [17]

As always, content on this blog reflects my personal views and not those of any organization with which I am associated.

[1] https://ecotourism.org/what-is-ecotourism/

[2] https://www.oist.jp/about/facts-and-figures

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryukyu_Kingdom

[4] https://www.jetro.go.jp/ext_images/austria/images/OkinawaGOTF2024/OkinawaProfile.pdf

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryukyuan_diaspora

[7] https://www.jpf.go.jp/e/about/award/50th_anniversary/message/2004-01.html

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shuri_Castle

[9] https://yoshida-brothers.jp/profile/en/

[10] https://www.reddit.com/r/tumblr/comments/mg9p10/tbh_bae_idgaf/

[11] https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/gettysburg

[12] https://www.sca.org/

[13] https://radicalmoderate.online/face-masks-and-social-distancing-part-1/

[14] https://radicalmoderate.online/the-world-of-miyazaki-paradoxes/

[15] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/projects/indo-pacific-leadership-lab

0 Comments