<– Start at the beginning of the Climate Lab series

Around the end of my time in grad school, I remember attending a conference at which we heard an amazing keynote address from sustainability thought leader Paul Hawken. [1] During his time on stage, he shared a lot of fantastic, relevant information that now (more than a decade later) escapes me. What I do remember was that as he neared the end of his presentation, describing the vast interconnectedness of our world, the sound of a violin quietly joined his voice. He left us with the thought that the beautiful, rich sound of a Stradivarius violin is considered to be – in part – a result of the Little Ice Age in Europe in the 14th century: slower tree growth produced smaller tree rings, therefore more consistent density throughout the wood, and therefore a resonance distinct from modern violins. [2]

His presentation was not about violins, of course, but as the music swelled at the conclusion of his speech, I felt held in the moment. His illustration of our world as a complex web of cause and effect inspired me to consider the fact that even I could make a difference with my actions. I turned to my classmate Becky and expressed how incredible the presentation was and how full of purpose I felt. She very matter-of-factly looked back at me and asked: “OK, so what are you going to do differently tomorrow?”

What Will You Do?

I was floored. I had no idea how to answer her question. Even if I could make a difference, as Paul Hawken had just told everyone in the room, I had no idea what my next steps would or should be. We had spent a year together in our sustainability-focused MBA program learning relevant theories, tools, and practices, but I was at a loss for what – specifically – I could do to translate this sense of passion for protecting our world into meaningful actions that could help achieve that goal. Maybe it was a lack of real-world perspective, or maybe I was still waiting for someone to grant me the formal title change from “student” to “leader.”

Does the role of “leader” need to be granted by someone else? Do you have to consider yourself a leader to exercise leadership? To both questions I emphatically say no.

Photo courtesy of: Jyothsna Wudayagiri Singadivakkam

Becky’s question has resurfaced several times over the years, more often when I am feeling inspired by something I recently learned. That mentality permeates this blog: even if I don’t have an answer, my next step is to learn more until I have a clearer path forward. And that question has played a central role in conversations among my Climate Lab cohort, especially after returning from the first leg of our travels in Hawai’i. A major component of this lab is not just to learn from the program and from each other, but to apply that learning back home in our own work, and then share what has and hasn’t worked with each other, so we can continue to learn in an adaptive and iterative way.

In the last few posts in this continuing Climate Lab series, I wrote about my own reflections from our time in Hawai’i, [3] but revisiting those experiences as a group after returning to our respective homes reinforced some concepts that resonated with many of us:

- challenging traditional expectations of what leadership is – and recognizing when it’s OK to step up or let go as a leader,

- focusing on understanding the decision making process, rather than simply following the leader or the decisions themselves,

- getting comfortable with trial and error – and recognizing that failure is not only inevitable but necessary for meaningful improvement, and

- connecting narratives to reality in an effective way to illustrate lessons learned and ways to apply those lessons in the future.

Several of us noted that our teams back at work were curious, if not excited, to hear about what we had learned in Hawai’i. I gave a presentation to my team that closely followed the structure of my blog series (since writing about this experience is helping me to process and incorporate what I’ve been learning!) But there was still the question of “so what?” which is rapidly becoming the central question being posed to us in our Climate Lab cohort. It was clear that what I bring home shouldn’t just be a presentation for my team to sit through, but rather a framework for us to improve our effectiveness as an organization.

Complexity Leadership Theory

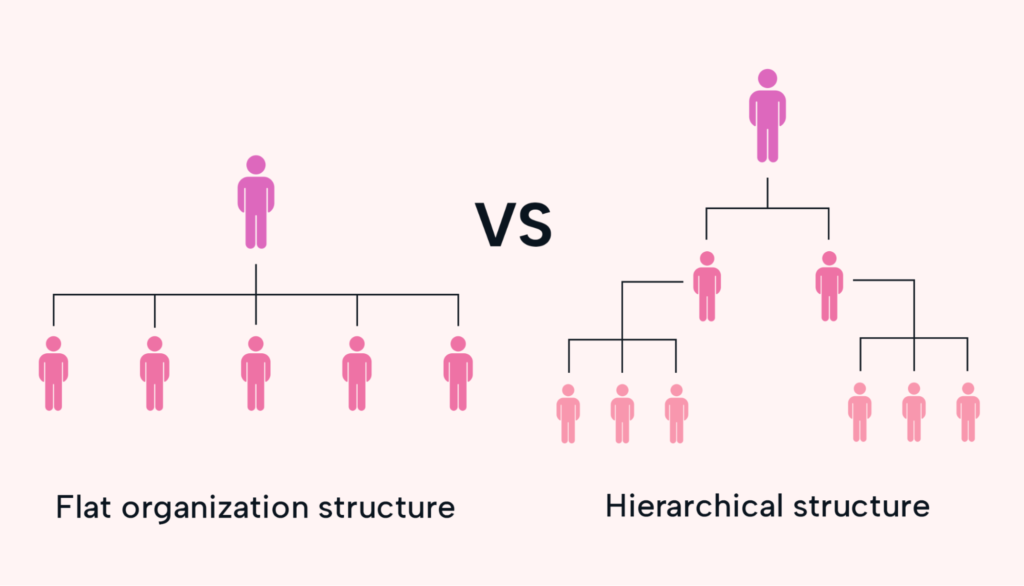

Understandably, shifting organizational culture is no small task. Speaking just for American work culture, we have some deeply ingrained ideas about what org charts, work days, and individual responsibilities should be. Fortunately, we’ve seen many workplaces become more flexible with those concepts over the course of the pandemic, but a lot is still determined by the type of organization we’re examining: are we looking at a small, nimble, flat startup or a large, bureaucratic institution with a lot of inertia? The size, structure, revenue sources, and even the purpose of the organization can have a huge impact on culture, including which of the concepts listed above can even be applied to – and adopted by – the organization.

The answer, I hope, is yes – because that’s what we’ll need to do to generate climate change solutions that work at the global level.

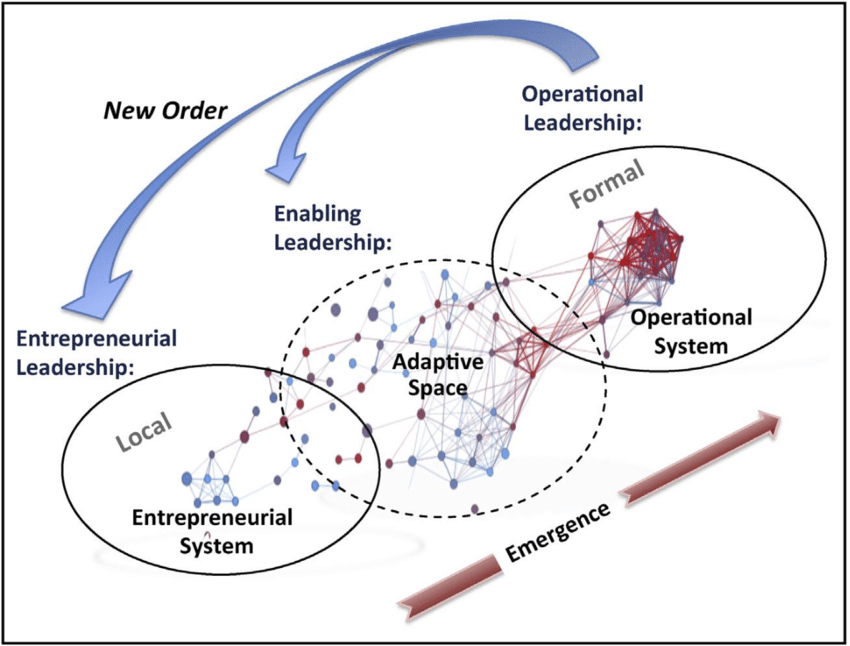

Image credit: [4]

We have already established that our work to create solutions for climate adaptation involves aiming at a moving target. Consequently, one of our first virtual sessions post-Hawai’i focused on the concept of Complexity Leadership Theory (CLT), which recognizes necessary approaches for dynamic (not static) environments. [5] We have also established that part of our work is to apply our Climate Lab lessons where we can back home, so part of learning about CLT involved evaluating the dynamics within our own organizations and how we approach dilemmas as leaders.

A note on definitions: our discussion involved making a distinction between “complicated,” which is something that requires simplification, and “complex,” which requires an understanding that when you change one thing, it changes something else, and so on. An organization navigating complicated (not complex) issues may appear bureaucratic, hierarchical, and slow to change, while an organization navigating complex (not complicated) issues may by necessity appear more collective and nimble in its approach, as it has to respond to sudden and unpredictable changes resulting from interactions between different elements of the system. Given the complexity of factors and the ticking clock associated with climate change, our next step as a cohort was to evaluate the traits associated with the more adaptive responses and to determine how we can create more adaptive cultures within our own organizations.

Applying Lessons

In examining our own leadership behaviors, we asked some difficult questions of ourselves and of each other. Most notable for me was the question of how much of my leadership style relies on managing interactions vs. formally leading; or, to put it very simply, on asking vs. answering questions. It is very important to me to promote open discussion and provide opportunities for others to step up, but it can be incredibly difficult when time is short and stakes are high to leave space for questions, alternate ideas, and dissent. And I don’t think I’m alone in deferring to formal titles, roles, and hierarchies in times when decisions need to be made quickly. In fact, I feel like I am still inclined to wait for someone to give me something to do if I don’t hold an official leadership role (not unlike how I felt at that conference in grad school).

Image credit: [6]

I believe there are absolutely times when respecting the established chain of command is critical (immediate life-or-death situations, perhaps), but I also believe those instances are relatively few and far between in most lines of work, and that there still needs to be a debrief afterwards to get clarity on why certain decisions were made and to better understand the process used to arrive at those decisions (and whether the process worked or not). Part of the problem when we’re talking about humans is that our nervous systems have evolved to respond to life-or-death threats, and they’re very bad at differentiating between an unpleasant tiger and an unpleasant email. [7] And when stressors appear (no matter the source), our bodies try to protect us by sending us into fight/flight/freeze mode, which can be one of the worst things for us when dealing with workplace problems.

I know, for myself, that stress contributes to a scarcity mentality (especially given my focus on making sure my company has enough money coming in the door so my teammates can do their jobs), and a scarcity mentality makes me want to fight over slices of the funding pie, which pulls me away from collaborative, big-picture thinking with potential partners. I know that collaborative, big-picture thinking is critical to developing realistic, implementable solutions to climate change, but that, first, requires getting over the “I win/you lose” mentality and, second, requires admitting what I don’t know (or worse, risking being wrong when confronted with new information), which is really scary for people in leadership positions.

But I keep coming back to this idea that no one has all the answers, and no one is tasked with figuring out one solution for everything on her own (because there is no one solution, either). When asked what I could do to foster a more effective approach to dealing with complexity in my organization, I suggested that I could lead by reflecting questions back to my team, either as a way to encourage them to voice their own perspectives if they haven’t already or as a way to gently guide them to perspectives that they haven’t considered yet. (I know from experience that any good therapist uses that same technique!) And while I already make use of questions when I don’t have a good sense of which way to go, I’ll be curious to see what happens when I use them to proactively challenge my own assumptions.

~

There will be more to come on this journey of self-exploration and application of lessons in the weeks and months ahead. In the meantime, thank you for reading!

The Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab [8] is a program of the East-West Center, [9] with support from the Japan Foundation. [10]

As always, content on this blog reflects my personal views, and not those of any organization with which I am associated.

[3] https://radicalmoderate.online/climate-lab-hawaii-insights/

[6] https://www.usemotion.com/blog/flat-organizational-structure

[8] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/projects/indo-pacific-leadership-lab

[9] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/

0 Comments