<– Start at the beginning of the Climate Lab series

Climate Lab: Hawaii, Part 5 – Insights, Continued

“You must trust and believe in people or life becomes impossible.”

— Anton Chekhov

It is nothing short of a privilege to travel across the world and have an experience that shifts your perspective, and I feel incredibly fortunate to be one of the 16 fellows chosen for this climate lab cohort. The first third of the program has already changed how I look at my work and how I want to bridge gaps to create realistic, actionable steps that will lead to long-term benefits for the planet and the people on it.

But if the first piece of the equation is gaining the skills and perspective to make a change in the world, the second piece is figuring out how to do it – and implementing a plan is not simply a matter of creating the plan and saying “go.” There needs to be buy-in and feedback from as many parties as possible throughout the process in order to create something successful, but coordinating that many people or groups takes a long time, a lot of effort, and the ability to recognize that what you had envisioned might not be the best path forward. And all of that feels incredibly difficult, especially in what seems to be a particularly polarizing topic during a particularly polarizing time.

“Oft hope is born, when all is forlorn”

I will admit that there are many days when I feel some level of despair as I tackle difficult subjects in my work, personal life, here on this blog, and in this climate lab. By the end of our week in Hawai’i, we had been face-to-face with some dismal pictures about the future impacts the islands would face from rising sea levels, stronger storms, and longer droughts, as well as the human health costs of energy development – even renewable energy, which is supposed to be the “good” option. Consequently, it was a smart move on the part of our program to check in with us about how we were feeling and whether we believed – or hoped – that positive change was still possible. But, in the end, we were presented with this encouraging thought: hope exists in the face of despair, possibly because of despair (similar to how you can’t display courage without first being afraid).

Image credit: [1]

To be clear, when I say “hope,” I don’t mean the blind optimism that everything will somehow be OK, but rather the belief that things can be made better through action. There is a very powerful story in Jim Collins’ book Good to Great [2] that explains the difference through the lens of Admiral Jim Stockdale’s eight-year imprisonment in a POW camp during the Vietnam War. Stockdale explained that it was the optimists – the ones who thought “we’re going to be out by Christmas,” “we’re going to be out by Easter” – were the ones who didn’t make it. In Stockdale’s words, “You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.” And that is what Collins refers to as the “Stockdale Paradox.” [3]

Over the years, I have certainly lost the cockeyed optimist quality of my youth, with a healthy dose of cynicism filling those gaps. Nevertheless, I still get out of bed and go to work in the morning because on some level I have to believe that some action of mine can create a net positive benefit for someone else, somewhere down the road. I suppose if hope weren’t a factor, I wouldn’t be in this climate lab; the climate lab itself may not even exist, because why bother training us if there’s no hope in our efforts making a difference? But I also know that this work is difficult, and there are many times that I have felt hopeless after a hard day at work or simply watching the news. And that’s when I turn to stories to lift my spirits.

I’ve already mentioned the concept that when it comes to climate change, we’re writing this story as we go, with no clear idea of how it will end. But stories of triumph, no matter how small, remind us that our actions can make a difference. Hearing about others navigating times of uncertainty and adversity have always helped encourage me – and those stories don’t even have to be nonfiction: during pandemic lockdown in 2020, my husband and I certainly watched “Lord of the Rings” more than once. (That’s a quote from the book in the section header, by the way. [4])

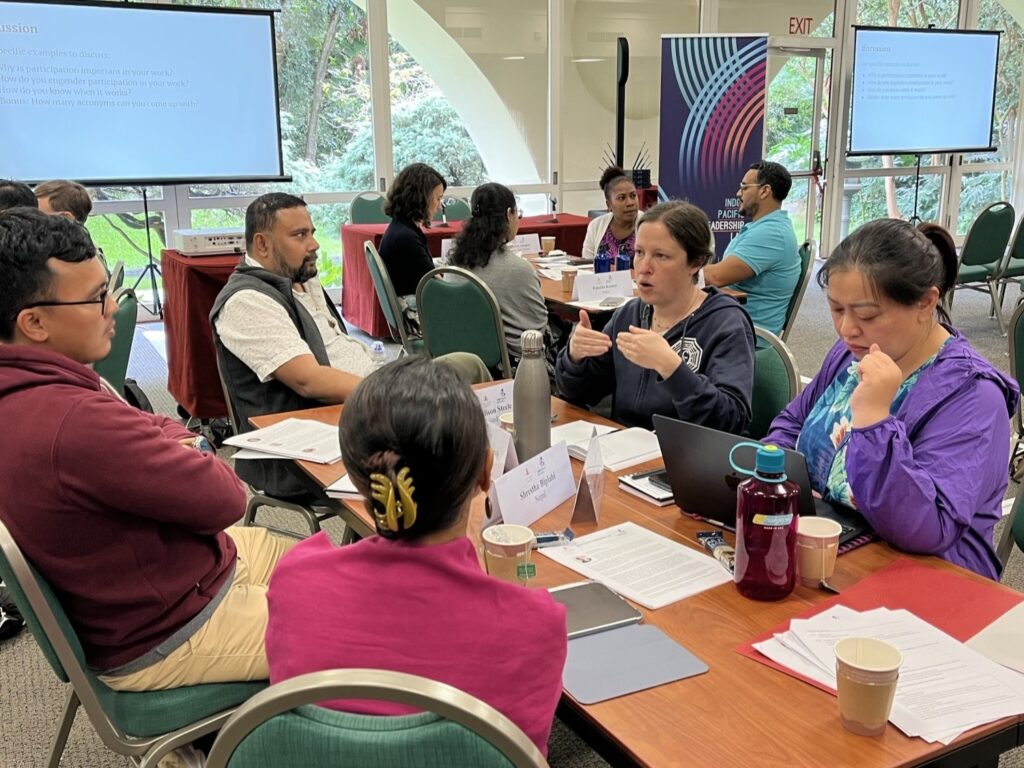

Image courtesy of East-West Center: [5]

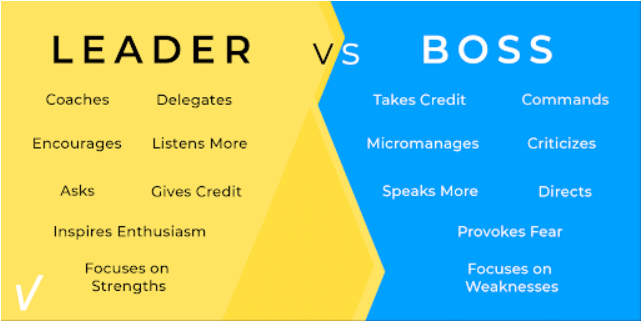

Leading From Behind

Stories are incredibly useful for conveying hope, and they’re not just a medium for learning; they’re also a medium for leading. A good leader should inspire others, but it’s not the leader that people should be following – it should be the common goal toward which everyone is striving, with that work enabled by the leader. And as the head of an organization, I cannot convey how much I appreciated it when someone in one of our classroom sessions said “Leaders are useless and inefficient. They have one job: to set the space so everyone else can do their jobs.” (I have often said that my job is to make sure that everyone else has what they need to do theirs.)

When we think about expectations for a leader (or at least when I do), descriptions like “perfect,” “complete knowledge,” and “incapable of failure” come to mind. That’s what we want from our leaders, but ironically, failures are necessary for creating a good leader. Mistakes are some of the best teachers, and the recognition of incomplete knowledge forces that leader to bring experts together from different areas. (Note: life experience is an important area of expertise that gets overlooked frequently.) In order to learn from mistakes and admit what we don’t know requires a willingness to lean into the discomfort of uncertainty, to be upfront about our own limitations, and to adjust the plan when new information comes to light. But that’s a difficult ask from anyone, especially when the expected standard is perfection.

The way I’ve tried to get around that in my job is by starting with what I don’t know. I am the head of a public health organization, but my background is in physics and sustainability. Nevertheless, it’s up to me to bring together people with relevant expertise, paint a picture based on what we know, and then figure out how to fill the knowledge gaps that remain. And because I readily admit that I don’t have all the answers, our approach involves more of a commitment to our goals, rather than an attachment to specific methods of achieving them. When it comes to creating plans, I rarely do that in isolation, primarily because I rely on the expertise of those on my team who have valuable, diverse perspectives and understand their jobs far better than I do.

Image credit: [6]

That approach leaves space for learning from mistakes and accepting the realities of failure, as well as understanding that life is messy and that there is no one “right” answer. It also has resulted in (I believe) far more success for our team than if I had simply dictated decisions from a vacuum, and that tracks with another theme in our climate lab discussions: the importance of decentralized power. I recognize that consensus isn’t always possible, but I strive for it whenever I can because these efforts are not mine alone. And I’ll admit that that’s something I wasn’t always able to say.

Passing the Torch

Being an only child (and an only grandchild), I’m used to being the center of attention, and I grew up believing that I could do anything I wanted to. Since I wanted to save the world, somewhere deep in the recesses of my brain I think I truly believed I could – single-handed, savior complex, and all. I think the biggest lesson I may be taking from this program is coming to terms with the fact that I won’t solve this problem myself, and that it won’t be solved in my lifetime. When we discussed that concept in one of our first sessions last fall, I felt truly disappointed and frustrated to think that we couldn’t just power through, and make it happen, and be done with it. But I’m coming to realize that it’s not my job to do it all; it’s my job to do my part, one piece of a massive, global effort – and, in a way, that’s starting to feel like a relief.

Thinking about addressing climate change as a group effort means thinking about who all can contribute now, and how, but it also means thinking about how efforts will continue to evolve in the future and what will be needed when new people step up as leaders. (As Doc Brown from “Back to the Future” would say, it’s a matter of thinking fourth-dimensionally. [7]) So as a leader, part of my work is to think about how we’re going to solve today’s problems, but it’s also important for me to think about how I can support others’ efforts to grow into positions of leadership for the future – and that means giving them the opportunities to try, fail, learn, and grow on their own, in as supportive an environment as I can manage.

Image credit: unknown closing reception attendee

It’s important not to think of leadership as a permanent, unchanging state of being. Leaders step up when needed, being available in a given function when it makes sense. But they also step back and allow someone else to bring value when that makes sense. It was strangely comforting to think that my leadership need not be forever, nor in the same form it is now. (And while I don’t have plans to go anywhere any time soon, it was a bit freeing to hear it put that way.) And given that state of flux, it seemed to me when considering this concept that leadership roles are far more frequent and accessible than we tend to think. Leadership is something that happens when certain abilities and certain needs cross paths at a given point in time – all that is needed is for someone to be there for that opportunity and have the will to take action. That type of “leadership moment” probably presents itself to more of us and more often than we realize, but many of us don’t necessarily think of ourselves as leaders (probably for some of the reasons laid out above) and consequently let those opportunities pass unmarked.

So, with that idea of “leadership moment” in mind, I will wrap up this extra-long summary of my time in Hawai’i with a question that was posed to us: the number of people who could have been born in your place is huge – what are you going to do with this opportunity?

~

There will be plenty more to share as this journey continues, but for now thank you for reading!

The Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab [8] is a program of the East-West Center, [9] with support from the Japan Foundation. [10]

As always, content on this blog reflects my personal views, and not those of any organization with which I am associated.

[1] https://www.reddit.com/r/lotr/comments/b84hbd/he_never_actually_said_that_he_would_destroy_it/

[2] https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/76865

[3] https://www.jimcollins.com/concepts/Stockdale-Concept.html

[4] https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/65317-oft-hope-is-born-when-all-is-forlorn

[5] https://www.flickr.com/photos/eastwestcenter/albums/72177720315300633/with/53573854754

[6] https://blog.valorperform.com/leadership-qualities

[7] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0088763/

[8] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/projects/indo-pacific-leadership-lab

[9] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/

0 Comments