<– Start at the beginning of the Climate Lab series

Hawai’i, Part 2 – In the Field

“The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.”

– William Shakespeare, As You Like It

Our brains are hardwired for absorbing stories and making sense of the world in the form of narrative. We evolved that way over millennia in order to hold onto data before there was writing. Our brains are so used to processing information in story form that they fill in missing details in order to make sense of incomplete data (whether we want them to or not). And while our brains are pretty bad at paying attention to and recalling raw data, they’re great at retaining stories and the concepts they convey. [1]

Hawai’i has a strong tradition of oral history that remains today in the form of chants, songs, dances, and “talk story,” which involves sharing one’s own history, experiences, and feelings. [2] During the week I was on Oahu for my climate adaptation leadership lab, we used talk story sessions to get to know each other and the residents we met during our field visits. And while I scribbled furiously in my notebook to try to hold onto all of the important information our hosts shared, it was the feelings and the lessons of their stories that stuck with me afterwards.

I felt like almost every story I heard that week involved some kind of unintended consequence from a careless act that rippled across the island, more often than not involving the introduction of an invasive species. Sometimes these consequences followed well-intentioned actions, which were sometimes based on practices that have worked well elsewhere, but it is ultimately the result, not the intention, that remains. And some of these shocking stories made it clear to me that for as many years as I have been involved in energy, health, and community engagement, I am still prone to creating easy, palatable stories for myself based on incomplete information.

The Price of Wind Power

I am a proud consumer of renewable electricity at home (90% wind), and I smile whenever I see fields of utility scale solar installations or banks of wind turbines as I drive along the Pennsylvania turnpike. Being a Pennsylvania native, I have long supported a transition away from fossil fuel extraction (a core component of our state’s industrial legacy, if not identity) to a clean energy economy that generates green jobs in energy efficiency and renewable energy production. Once I learned that we would be meeting with a community on Oahu’s north shore that had wind turbines nearby, a development that supports Hawai’i’s transition to 100% renewable energy, I was intrigued to hear more about the residents’ experiences.

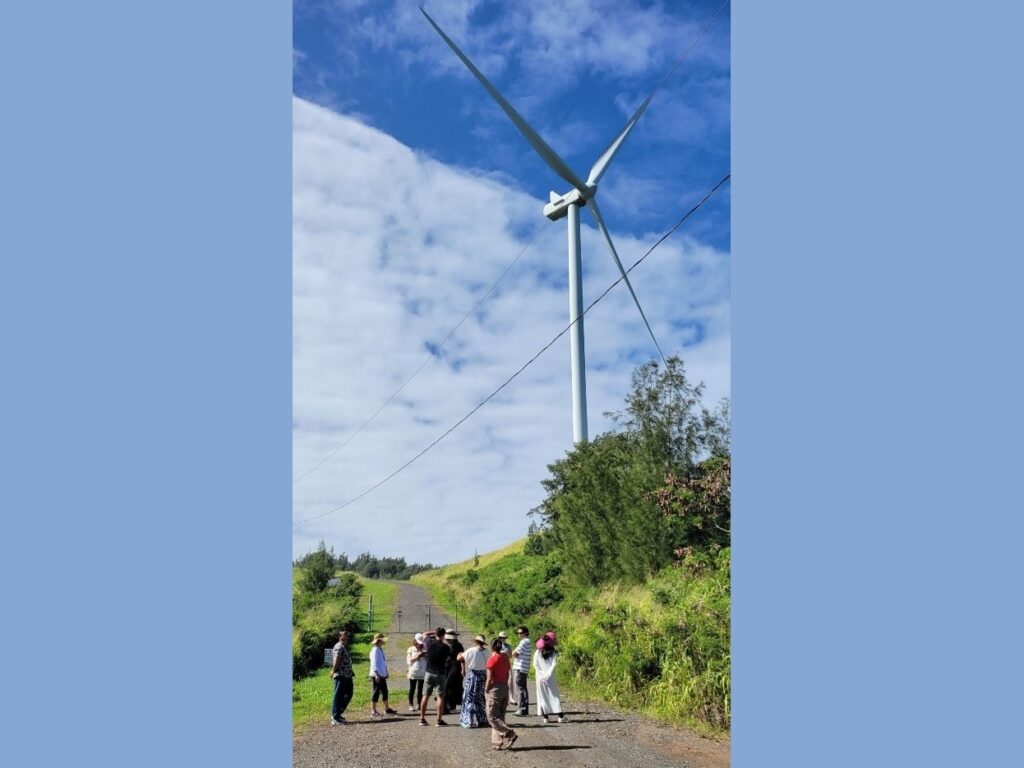

When we arrived in what struck me as a very blue collar town, I was not expecting to hear stories similar to those I encounter on a regular basis back home, on the front lines of shale gas development. Among the 20 wind turbines surrounding the town of Kahuku are some of the tallest in the United States at 568 feet, and in their flickering shadows, a group of mothers has organized to advocate for the health of their community, particularly their kids. We were met by Sunny, one of the moms, who guided us to the elementary school and several homes in the town to hear from people who have begun experiencing negative reactions to the low-frequency noise and the strobe light effect created by the spinning blades. Several people described developing symptoms including vertigo, tinnitus, tachycardia, sleep deprivation, and migraines since the turbines were constructed – and one mom explained how her symptoms disappeared while vacationing on the mainland. Although I couldn’t find it in my notes, I also remember someone talking about epilepsy, which is a real enough concern that there are existing guidelines for reducing seizures among individuals with photosensitivity near wind turbines. [3]

Image courtesy of East-West Center: [4]

The legitimacy of “Wind Turbine Syndrome” has been debated for years, but working in the field of public health and regularly speaking with frontline residents who feel they’re not being taken seriously, I was suddenly struck by unexpected echoes of my work back home. After a quick skim of the available literature on “wind turbines” and “health impacts” in Google Scholar, it is clear there has not actually been much research conducted on the subject in the last decade. Some studies are inconclusive (which, based on how these studies are constructed, means that they didn’t find a connection, not that they’ve proved there isn’t a connection), while others have noted that sensitive members of the population may experience unfavorable health effects, such as physiological and psychological reactions, sleep disturbances, and difficulty concentrating, but that those outcomes are rare. [5]

While these moms in Kahuku have been told that there is no proof of causation between wind turbines and adverse health impacts, it is important to remember a few things about public health research: 1) correlation (not causation) is enough to justify caution in the eyes of public health professionals, and 2) demonstrating causation using epidemiologic studies (which examine broad trends across a population) is extremely difficult to do, especially when you’re working with small sample sets (which is usually the case with rural communities). But regardless of what the studies say, nothing changes the fact that the community’s concern for their kids is real – and no matter who you are, having your emotions dismissed is a demoralizing experience.

All that said, several of the articles I skimmed indicated that there is no evidence of health harms when wind turbines are sited appropriately, which is one weighty disclaimer, especially considering that we learned during our visit that two of the Kahuku turbines are sited closer to property in the community than legally allowed. And again, it is difficult to determine a “safe” distance from industrial infrastructure, even after extensive study. Therefore, those required minimum distances, “setback distances,” are more likely to be established by what policymakers determine to be how much risk to the population they’re willing to accept. The setback distance for wind turbines in Hawaii is 1-to-1 (i.e. as far away as the structure is tall), and the community is pushing for a 1.25-mile setback, but we were also told that a 3-mile setback would eliminate any new wind development on the island entirely – a non-starter for a state trying to achieve 100% renewable energy.

Image courtesy of East-West Center: [6]

The Value of People Power

Despite attempts at community organizing, and despite a desire to participate, it can be difficult to get involved in what can be an opaque process of speaking at public hearings or submitting written comments. On more than one occasion, we were told, public comment periods passed before community members even knew a project was proposed. And even when some of these moms knew what they had to do ahead of time, it wasn’t always possible to get time off of work or arrange for childcare. Feeling they had no other options, community members organized nonviolent civil disobedience to slow, if not prevent, the construction of a new set of turbines. [7] While the project eventually did move forward, one of our hosts told us that the high profile nature of their opposition helped scuttle a proposed project in a low-income community in another part of the island.

And the people who told us their stories were generally clear that they are not opposed to wind development; they are opposed to wind development where it negatively impacts their health, the environment, and the local wildlife (including the ‘ope’ape’a, an endangered Hawaiian bat [8]). I also didn’t realize before this visit that wind turbine blades can’t currently be recycled, meaning that parts of these behemoths towering over Kahuku in the name of green energy are destined for a landfill, location to be determined. [9] What we heard from these residents was that they’re good, hardworking people who feel they’ve been treated unjustly, and that they want to see thoughtful wind development that respects the land and the people of Hawai’i as much as they do.

I know enough about energy to know that there are costs associated with any source we use, including renewables. We need material resources to create energy, whether it’s methane gas fracked out of the ground or rare earth metals mined to create solar panels. I regularly preach the value of energy efficiency on this blog, pointing out that the cheapest, cleanest kilowatt-hour is the one not used, but that requires material resources too. (We had a lot of flame-retardant cellulose pumped into our attic three years ago for the purpose of saving energy. [10]) And any of these choices will have positive and negative impacts on different businesses and humans … and ecosystems involved in the supply chain.

Image credit: [11]

Ultimately my point here is that – as with any decisions we make – we need to weigh the consequences of those choices… but that is made incredibly difficult when we don’t have all the information. I thought I had a relatively informed perspective on wind power, but it took a 5,000 mile flight and meetings with impacted residents to understand how limited that perspective was – and it’s not realistic to expect everyone to have the time, energy, money, or desire to dive into every topic to make the “right” decision. So given that limitation, it is incumbent upon project developers, government entities, and industry operators (yes, even them) to ensure that community voices are centered in energy development work from the beginning. If they’re not, the project will be far less likely to meet with success on a number of fronts.

~

And speaking of success, next week we will continue with a look at a community-driven project happening just down the road from Kahuku.

Thanks for reading!

The Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab [12] is a program of the East-West Center, [13] with support from the Japan Foundation. [14]

As always, content on this blog reflects my personal views, and not those of any organization with which I am associated.

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zGrf0LGn6Y4

[2] https://allgoodtales.com/storytelling-traditions-across-world-hawaii/

[3] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18397297/

[4] https://www.flickr.com/photos/eastwestcenter/albums/72177720315300633/

[5] https://europepmc.org/article/med/38104341

[6] https://www.flickr.com/photos/eastwestcenter/albums/72177720315300633/

[7] https://kawaiola.news/cover/kahuku-where-the-salt-winds-blow-and-the-turbines-turn/

[8] https://www.nps.gov/havo/learn/nature/hawaiian-bat.htm

[9] https://www.nationalgrid.com/stories/energy-explained/can-wind-turbine-blades-be-recycled

[10] https://radicalmoderate.online/my-cabin-doesnt-leak-when-it-doesnt-rain-part-1/

[11] https://www.civilbeat.org/2021/04/kahuku-wind-farm-case-goes-before-hawaii-supreme-court/

[12] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/projects/indo-pacific-leadership-lab

[13] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/

0 Comments