In my “Productivity Hack” series earlier this year, I mentioned that I had applied to a highly selective global leadership program focused on community-oriented solutions to climate change. [1] In that post I described the value of simply going through the application process, which gave me the opportunity to consider the past two decades of my studies and work in the context of where I am today and the change I hope to support in the future. For the record, I had no expectations of actually being accepted into the program, but that didn’t stop me from thinking about what my next steps might be in the fight to protect our planet and the people on it.

A few weeks after the aforementioned post went live, and the morning after an emotionally raw community meeting I attended for work, I had a moment of quiet time on my front porch in the morning sun, during which I felt compelled to state an intention – to whomever/whatever might have been listening – that I would go where I was needed to fulfill my purpose. I have had two such moments in my life before: one praying at a Hindu temple on New Year’s Day and the other walking through snowy woods outside Nagano, Japan. Each of those moments preceded an opportunity to step into a new phase of my journey in public health and environmental protection. [2]

Send Me Where I Need to Go

Of course, we all know the adage “be careful what you wish for.” I certainly got what I asked for both of those times: first moving into the nonprofit sector to develop energy efficiency and home health resources in low-income Pittsburgh communities, and then taking the helm of an organization that pushes for stronger public health protections in the face of oil and gas development on the local, state, and federal levels. These steps were big changes for me that felt nothing short of daunting at times and that really forced me to grow, professionally and personally. Rewarding? Of course. Challenging? Every day.

And now, I have gotten my wish yet again. Just a few days after that moment on my porch, I received a completely unexpected acceptance letter from the climate program in question.

Image credit: [3]

There were a few reasons why I did not expect that letter. To say nothing of my intense impostor syndrome, this competitive application process would ultimately result in a cohort of 16 participants from a list of about 30 eligible countries. On top of that, the program had been described to me as focusing on climate change adaptation strategies, and I believe my work is more closely tied to climate change mitigation. Finally, maybe the most obvious, is that the program is called the Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab, and Pittsburgh is notably not located in or anywhere near the Pacific.

All that said, I do believe there is connective tissue there, and I was grateful that the selection committee agreed with what I had to say on that front. In dealing with climate change and pollution, we cannot look at separate pieces in isolation, but rather must examine them as part of a broader system. The lifecycle of fossil fuels ends with greenhouse gasses accumulating in our atmosphere and plastic waste building up and breaking down in our oceans, but the lifecycle begins with extraction – and Appalachia is no stranger to fossil fuel extraction.

Industrial Legacy

The Marcellus and Utica shale plays, which lie underneath parts of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, and neighboring states, represent what is considered to be the second-largest fossil gas reserve on the planet, according to the American Petroleum Institute. Such a wealth of gas can be burned for heat or electricity generation, exported to other states or countries, [4] or used to create new products, such as plastics [5] or hydrogen fuel. [6] But climate scientists recognize that we are at a critical time when we need to be extracting less in the way of fossil fuels, not more.

Image credit: [7]

However, the situation is far more complex than that (and far more nuanced than I’ll be able to cover in a 1400-word blog post) once you look at the economic systems and regional identity in a part of the country that has been associated with heavy industry for generations, where there are legitimate fears of boom-and-bust cycles and of decisions being made in Harrisburg and DC by politicians who have never spent any time here. There is a lot of pushback against the idea of ramping down fossil fuel extraction because of a pervasive fear that such a move will destroy the economy and the fabric of rural communities.

One of the points I raised in the application process was that we cannot address the climate crisis with a transition away from fossil fuels without having an alternative in place – an alternative that represents clean, safe, well-paying, long-term, sustainable jobs. As long as we see continued manufactured demand for oil and gas products propping up the supply side, we will also see continued adverse impacts to the health of people living near fossil fuel infrastructure, to the safety of people in regions most heavily hit by climate change and pollution, and to the long-term wellbeing of the planet.

While I don’t necessarily think of my daily work as climate change adaptation, there are clear connections because none of these issues can be examined in a vacuum. The less we mitigate our impact, the more we will have to adapt to climate change. The more we demand a supply of fossil fuels and products made from them (including plastics and “clean” methane-based hydrogen), the more pollution we will deal with in the long run. The sooner we can develop economic alternatives and support our workforce through a just transition to renewable energy jobs, the less fear (and resistance) we will see about oil and gas jobs going away.

The Evolution of Engagement

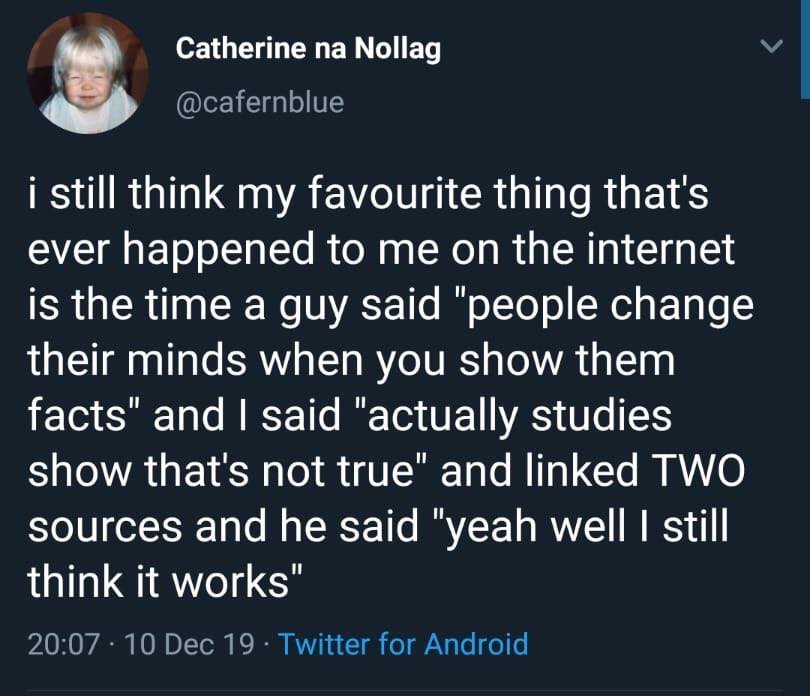

The economics piece was an especially relevant aspect of this issue in Pennsylvania this past week, as I saw its influence in several state-level decisions that left me feeling frustrated and discouraged. I have long believed at a fundamental level that as long as people have accurate information, they will be able to make informed, responsible decisions. Unfortunately, we saw that was not the case during the COVID-19 pandemic, laying the groundwork for a political crisis of faith for me. [8] Similarly, I just witnessed several examples in short succession demonstrating that that’s not the case in the context of my day job either, leading me to question the effectiveness of my contributions (or at least my approach) as the head of a public health organization.

Image credit: [9]

Intellectually I know that simply providing facts to someone who disagrees with you will not help to sway them; many times that approach will serve to make that person become even more entrenched in long-held beliefs, a phenomenon known as “belief perseverance.” [10] Humans are complex, emotional creatures, and we respond very strongly to fear and perceived threats to the status quo, self-assigned labels, and political/religious ideologies. I know that much of the anger and disappointment I felt this week was related to the gap between what I feel should be happening in Pennsylvania and what decisions are being made by politicians who don’t hold the same values or priorities… or data.

I fully recognize that I hold cognitive biases informed by my own life experience, and that something that seems like an obvious course of action to me may be a non-starter for someone else. I also recognize that comprehensive solutions to the climate crisis will require a wide range of perspectives and actions at the global, national, and local levels – there is no one-size-fits-all plan for the planet. To that end, I am very much looking forward to learning and sharing with the fellow members of my leadership lab cohort in the coming year, with what will no doubt involve a lot of trial and error. I also hope to document the process here as we go and will be curious to hear your thoughts and feedback as well.

~

Thank you for whatever you may be doing to combat climate change in your corner of the world. I’d love to hear about it below.

Thanks for reading.

The Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab [11] is a program of the East-West Center,[12] with support from the Japan Foundation.[13]

As always, content on this blog reflects my personal views, and not those of any organization with which I am associated.

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/the-greatest-productivity-hack-part-4/

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/new-years-resolutions-and-the-courage-to-be-disliked/

[4] https://radicalmoderate.online/renewable-energy-and-energy-independence-part-1/

[5] https://radicalmoderate.online/plastic-free-july-2022-part-3/

[6] https://radicalmoderate.online/hydrogens-rainbow/

[7] https://e360.yale.edu/features/for-low-income-pittsburgh-clean-air-remains-an-elusive-goal

[8] https://radicalmoderate.online/face-masks-and-social-distancing-part-4/

[9] https://m.facebook.com/DavidSuzukiFoundation/posts/10157914583673874?comment_id=10157924512468874

[11] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/projects/indo-pacific-leadership-lab

[12] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/

0 Comments