<– Start at the beginning of the Climate Lab series

This week’s post, the first to go live since the outcome of the 2024 presidential election, was meant to serve as a break from US politics – a breath of fresh air after weeks and months of nail biting. And while this post will take us back to discussions and assignments from my Climate Lab this past summer, these concepts are most definitely connected to things that are happening now – related to the election, what happens next, and my own efforts toward political depolarization (which have already raised some hackles over the past week).

Reflections

Upon our return from Fiji, [1] our Climate Lab cohort took a considerable amount of time to think, write, and talk about what resonated with us while we were there and after we came home. For me, the biggest question remained: “who gets to decide a course of action?” When we talk about equitable decision-making there is a lot of focus on including diverse voices at the table. The problem that remained, particularly in the Fijian villages we visited, was the tension between whether it’s the government making the final decision about what happens to them (from climate adaptation aid to relocation) or the village making the decision concerning their own future. In neither case will all relevant information be available to the decision maker, as I’ve raised in previous posts about finding solutions to complex situations. [2]

And further complicating this question, as we discussed it with our own multinational perspectives, is that decisions aren’t always made based on the same facts or perceptions. For example, not everyone has access to relevant data (I noted, thinking of the biased news sources in the US), not everyone with that information believes that climate change is happening (noted a classmate in Japan), and some people believe that climate change isn’t man made but instead a punishment from the gods (noted a classmate in Indonesia). It’s possible that if we all had the same information we would come to the same conclusions, but it’s far more likely that, based on our own lived experiences, we wouldn’t. It is very hard for the human mind to comprehend something we haven’t already experienced, which is why it’s so easy for us to slide into opposing camps based on what we know… and so hard for us to question whether we see the whole picture.

Image credit: [3]

Lived experience shapes our perception of the world. For me personally, I tried very hard to understand the fear and frustration of communities being impacted by sea level rise, more frequent flooding, and more intense storms. I also (silently) questioned whether their goals of building taller, stronger seawalls would work, and for how long. I wondered if it was ethical to impose my perspective on them, not having had their lived experience; I also wondered if it was ethical not to speak up if I had information that could demonstrate that a certain plan wouldn’t work or wouldn’t work for long. I was in Fiji to learn, not to take action (yet), but I had to ask myself: “if I’m truly trying to help, how do I approach this situation without seeming like their priorities aren’t also a priority of mine?”

Perceptions

One of the primary reasons I didn’t pursue a career in academia (despite the fact that I love researching, writing, and teaching) is that I wanted to be out in the world doing something about the problems we face, taking action and driving change. Of course, now that I see how complex some of our problems are, I recognize that barging in with a solution that doesn’t consider all the factors at play – including cultural norms, religious beliefs, or the priorities of those involved – can make things far worse. (It’s something that makes sense in theory, but after years of community engagement for my job, I will admit that I’m still learning that lesson.)

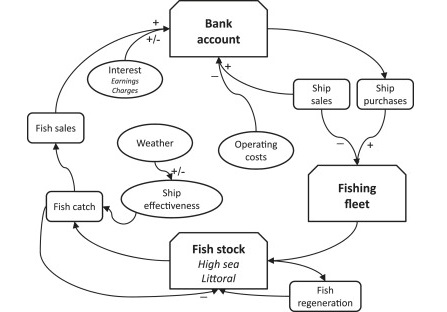

Interestingly, one of the reading materials in Week 1 of the Polarization Detox Challenge I’ve undertaken [4] was a writeup of psychology experiments in which well-intentioned participants made bad situations even worse with poorly informed, short-sighted solutions. Furthermore, the tendency upon seeing the negative outcomes of their choices was often to double-down on the same poor decisions. [5] I’ll just mention that if you’re sitting there thinking you’d do better, I participated in a fishing simulation during orientation week for my Sustainable Business Practices MBA program, and we absolutely destroyed the ocean ecosystem (as does every incoming cohort, every year).

Image credit: [6]

Balanced with the need for equitable problem solving is the fact that we need to act quickly. There have been many voices decrying how much harder climate efforts will become as a result of America’s November 5 decision, which will likely put us outside the possibility of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. [7] At the same time, some looking for silver linings are pointing to efforts happening at the state and city levels and in the private sector – efforts that can continue to spur green innovation and adoption of renewable energy sources. [8] I do believe there is something to be said for trying things out on smaller scales, stress-testing them, improving upon them, and expanding upon them as they become more effective. I won’t lie about my disappointment (to put it mildly) with the results of the election, but neither will I miss this opportunity to be as effective as I can in my own spheres of influence to drive connection and cooperation wherever I can, across stakeholder groups and across sectors.

The day I turned 40 (after some celebration and contemplation on my part), our cohort discussed the importance of fully understanding context in problem solving, as well as the ethics of community engagement, the importance of lived experiences, and the role of emotions in decision making. Certainly, emotions played a role in our presidential election: everyone I spoke to before the election cited fear over something, and they felt that their candidate would address that fear (regardless of data to the contrary, regardless of unintended consequences they may or may not have considered). Stories elicit emotions far more effectively than data (and I should specify: I know that stories are qualitative data; when I use the term “data” here, I’m talking about numbers, statistics, and all things quantitative), so it shouldn’t be a surprise that one of the themes that kept surfacing in our Climate Lab was the role of narrative in catalyzing action.

Actions

During our time in Fiji and the sessions afterward, we were asked to think about what we were going to do with this information, these lessons, our insights. Specifically, we would be tasked with creating a deliverable that could be useful in the course of our work and/or to our fellow classmates and/or to the next cohort to help them hit the ground running. In envisioning such a project, my mind kept returning to the idea of how to get seemingly opposing camps working together toward a common goal; creating some kind of connective tissue between stakeholders that (at best) don’t normally work together or even have animosity toward one another. My thoughts converged on a way to center community priorities but effectively pair them with relevant outside expertise to address their goals.

Image credit: [9]

It should be no surprise that I’ve focused my attention on getting people to work together at a time when my country feels more divided than ever. In the name of identifying and working toward common goals, the idea I posed for my project was something I called an “equitable facilitation framework.” The idea is to create a process in which a diverse set of stakeholders identifies an issue and a way to address it that recognizes multiple perspectives in identifying a solution and overcoming challenges to implementation. Recognizing that something like what I’m envisioning probably already exists (indeed it does! [10]), my project may ultimately be something more along the lines of writing a case study or theorizing how that framework could be applied to some of the complex problems we’ve seen on the ground during the course of our program.

As of the writing of this post, I’ve assembled a list of contacts to interview about this concept, particularly to point out what I’m not considering or where my assumptions fall short. Other things have demanded my attention in the months since I started these efforts, but it is still my intention to continue this work – even if it is only helpful to me. If it’s helpful to someone else, great – and if you’re interested in hearing more, there will certainly be more to come in the future.

~

For now, I’d like to hear from you about ways that you’ve had success in working toward common goals with an unexpected partner.

Thanks for reading!

The Indo-Pacific Leadership Lab [11] is a program of the East-West Center, [12] with support from the Japan Foundation. [13]

As always, content on this blog reflects my personal views, and not those of any organization with which I am associated.

[1] https://radicalmoderate.online/climate-lab-fiji-in-the-classroom/

[2] https://radicalmoderate.online/climate-lab-systems-thinking/

[3] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/training-exchanges/indo-pacific-leadership-lab-fiji-workshops

[4] https://startswith.us/pdc/

[5] https://docs.google.com/document/d/1IJgbrGSlUjyfel6bOlB07NaXGXHtECwqnzaXP4jtjE0/edit?tab=t.0

[6] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0964569111000780

[9] https://www.centerforsharedprosperity.org/

[10] https://www.centerforsharedprosperity.org/

[11] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/projects/indo-pacific-leadership-lab

[12] https://www.eastwestcenter.org/

0 Comments