Part 1 – The Scientific Method

When this post goes live, it will be five months plus six days since I started my new job as executive director at a public health organization. When this post goes live, it will be five months minus six days since our team began working from home 100% because of the pandemic. During this time, due to the nature of my work, I have had unprecedented access to a variety of experts: researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and ivory tower academics, public health policy specialists and health care providers who have seen a host of lung-related health problems in their patients over the years.

It has been an educational time for me, to say the least. I have had to learn about the operations of our company under “normal” circumstances, while also getting up to speed on what we need to do to ensure the safety of our staff and clients. Throughout all of this, I have not forgotten for a second that being in the top spot means that I set the tone for the organization, and that I am solely responsible for anything that goes wrong.

Now would be a good time to remind readers that this blog is a work entirely of my own and does not represent the position(s) of any organization that I represent, either as an employee or board member.

How we know what we know

Because of my job and because of the fact that all of my family members are in one high-risk group or another for the coronavirus, I have knowingly and unabashedly erred on the side of caution whenever possible. I have been in a physical quarantine bubble with my husband and cats for five months, but also a philosophical bubble with friends and colleagues who follow updates on testing rates and confirmed cases, compare strategies used in different countries, and read medical studies about transmission, symptoms, and lasting impacts of the disease.

Image credit: [1]

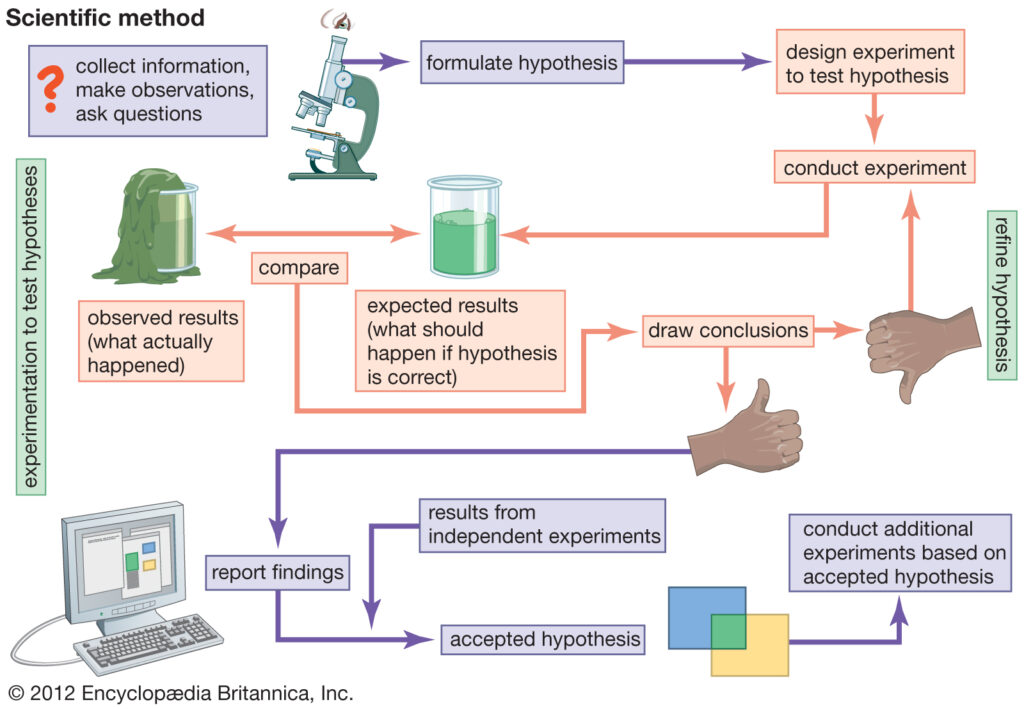

Coming from a scientific background myself, I appreciate that the scientific method doesn’t always follow a straight line, and what we think we know can change based on new information. This topic is something we discussed in my physics classes in college: the idea that we think of science as black and white because the things we learned in science class, such as gravity and classical mechanics, convey unrefutable certainty. That wasn’t always the case, though. We got to our understanding of classical mechanics through years of trial and error: dropping balls off of towers and rolling them down inclined planes to observe what was happening, draw conclusions, and test hypotheses. If we are dismayed by a lack of consensus in the scientific community (e.g. Is butter bad for you or not? Do artificial sweeteners cause cancer? etc.), it is because it takes time to gather information and perform tests that prove or disprove hypotheses, particularly where impacts on human physiology are involved.

However, as I have come to learn in my job, a public health crisis does not afford the luxury of time. Whether you’re talking about the outbreak of disease or impacts of a new chemical, if human health is being impacted now, it is the role of public health officials to take action quickly to prevent further harm. Doing this effectively is a balancing act that requires making educated guesses while working with the best information available. Any suspected paths of transmission must be shut down quickly to prevent further sickness, so experts can test different vectors of exposure and then modify their guidance as needed. Sometimes hypotheses are correct, and sometimes they aren’t; either way, something is learned, new questions are asked, the process is adjusted, and experts move to the next piece of the puzzle. When compared to learning “straightforward” laws of physics in a classroom, watching the scientific method in real time can be incredibly frustrating and disheartening, especially when the stakes are so high.

Backlash against science

While I didn’t expect everyone in the country to be in perfect alignment on how to deal with preventing the spread of the novel coronavirus, I never could have imagined that the response to a global pandemic could become so heavily politicized, that elected officials would be ignoring guidance from their top science advisors, or that a small but significant percentage of the American public would prioritize guidance from said elected officials over said science advisors.

I don’t know many people personally who are opposed to wearing masks, so it has been difficult to understand how wearing them has become such a political statement. Even my dad (the person I go to most often to understand the perspective of people more conservative than I) is angry at people who refuse wear masks in public. With the understanding that a lot of what I’m about to say is conjecture and generalization, I can appreciate that we live in a scary, uncertain time, and that there are emotional and psychological reasons why people would refuse to wear masks when going out in public. It doesn’t mean I agree; it means I understand.

Image credit: [2]

When my dad and I talked about the mask orders (and resistance to them), our conversation started with the concept that people don’t like to be told what to do, and yes, I’m sure that’s part of it. It makes sense that in a pandemic when we don’t have all the facts, including how long the virus will be a part of our daily lives, when we’re being told to stay inside and not gather in large groups, when people are losing their jobs and the economy is tanking, something as small as choosing whether or not to wear a mask can feel like one tiny way to retain some measure of control over one’s daily life.

It goes deeper than simple contrarian behavior, though. There is a level of desperation apparent in people who don’t comply with mask orders, as we have seen in those who are deeply angry, enough so that they berate employees,[3] grandstand about flouting regulations,[4] or resort to physical assault.[5] I in no way condone behavior of this sort, and people breaking the law must absolutely be held accountable, but I also want to examine the underlying issues of the steps that lead to a customer firing a gun at a store clerk over the mask order, as happened in my hometown last week.[6]

The Psychology of Uncertainty

Of course events like these are the exception, not the rule. The vast majority of Americans (71%) believe that masks should be worn all or most of the time in public places.[7] But it is disturbing that violent opposition happens at all and that a vocal minority gets such a disproportionate amount of the news time. I personally think that one of the biggest factors at play is here is that humans are extremely averse to uncertainty. Studies have shown that it is less stressful to have certainty of a bad future event than lack of certainty around whether or not something bad will happen.[8]

We also know that even when presented with facts, people are unlikely to change strongly-held positions. Confirmation bias is a real thing, and humans experience a rush of dopamine when processing information that supports their beliefs.[9] It feels good to listen to people who agree with you; it provides comfort, even if it’s not rational. But that too makes sense because anxiety suppresses rational behavior.[10]

In a time when we are still learning about the novel coronavirus, the world’s top epidemiologists don’t have all the answers, and that is scary. We’ve seen prominent scientists change position over whether or not masks are effective (we’re seeing that they don’t do much to protect you from others, but that they can protect others from you if you don’t know you have it).[11] Changes like that have eroded public trust, especially among people who don’t understand that trial and error is a huge part of science and public health.

We still don’t know everything about how easily the virus is transmitted, what percentage of people can be positive but not display symptoms, or how long the antibodies last if you’ve had it. These are all things we’re learning, but not having the clear answers that can only come with 20/20 hindsight can be terrifying. And for that reason, it is more psychologically comforting to cling to the false narrative of certainty that we’ll all be fine than it is to accept that we simply don’t know yet.

Tune in next week as I talk about my own Covid-19 scare and the steps we took at my house to protect our family.

~

I’d love to hear how you feel about the prevailing guidance on masks and social distancing. Please remember to be respectful to your fellow humans. We are all in this together.

Thanks for reading.

[1] https://www.britannica.com/science/scientific-method

[2] https://www.bakadesuyo.com/2019/12/change-someones-mind/

[3] https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/woman-slams-starbucks-barista-over-mask-rule-then-he-gets-n1232213

[4] https://popculture.com/trending/news/woman-banned-kicked-out-trader-joes-not-wearing-face-mask-suffers-sore-throat-week-later/

[5] https://www.pennlive.com/crime/2020/05/pa-man-accused-of-repeatedly-punching-female-store-clerk-for-telling-him-to-wear-face-mask-called-it-marshal-law-cops.html

[6] https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/04/us/man-gun-pennsylvania-cigar-shop-masks/index.html

[7] https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/06/25/republicans-democrats-move-even-further-apart-in-coronavirus-concerns/

[8] https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-right-mindset/202002/why-uncertainty-freaks-you-out

[9] https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/02/27/why-facts-dont-change-our-minds

[10] https://www.forbes.com/sites/briannawiest/2020/04/08/the-psychological-reason-why-some-people-arent-following-covid-19-quarantine-orders/#7cab4df06905

[11] https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2020/06/417906/still-confused-about-masks-heres-science-behind-how-face-masks-prevent

0 Comments