Part 4 – Supplying Food

My mom tells a story about how when she was young, family from England came to visit. Apparently the first thing they wanted to do was go to a grocery store and see all of the fruits, vegetables, and meats available, despite the season. We are amazingly spoiled for choice today — across the globe, but particularly in the US — and we are able to get pretty much whatever ingredients we want without thinking about when they’re typically available or how far they’ve traveled to reach us. It also makes us more likely to let them go bad before we notice.

Between land use impacts, methane produced by ruminant animals (such as cows and sheep), animal feed, and the processing of animal carcasses, there is a significant impact from meat and dairy products, as compared to vegetables. However, meat, dairy, and vegetables can all pack a punch in the carbon footprint arena when it comes down to the energy required to grow or preserve foods out of season, not to mention what happens when we don’t make use of the foods we buy.

Out-of-Season Footprint

I was shocked to find that meat products have seasonality to them, just like fruits and vegetables. It makes sense, but it had never occurred to me that animals taste different during different seasons, based on how their bodies respond to changes in food availability and weather. Because of this, livestock farmers try to time their slaughtering to maximize meat quality (and profit) and minimize their expense of feeding their animals longer than anticipated. However, many commercial slaughterhouses tend to operate throughout the year, evening out the seasonality of meat supply and their own operations (which benefits them, not the farmers).[1]

IF you’re going to eat meat, there are worse options than this.

Dairy supply sees seasonal fluctuations as milk production shifts with daylight, type and quality of feed, and pregnancy cycles of the cows. Milk quality (as indicated by fatty solids and microbial health) increases in order to provide the best nutrition possible for offspring,[2] and some farms choose to take advantage of that seasonality to give their cows (and their workers) an off-season break rather than producing milk year-round.[3]

Similarly, I never thought of eggs as a seasonal product, but hens lay less in the winter and ramp up their production in the spring. (Think of Easter eggs: there’s a massive surplus beginning around April.) Egg size and quantity vary with the seasons, but you can trick the hens with artificial light, which (as with continuous milk production) calls ethics and animal welfare into question.[4],[5] But as long as there is year-round demand, farmers will work to provide year-round supply, whether through forcing production off-season or freezing the product until supply is low.

We see additional GHG impacts whenever food must be preserved (usually through freezing or refrigeration), both on their way to the consumer and once they make it home. This is the case for all perishables, but according to the Our World in Data breakdown, we see some larger footprints among a lot of soy and dairy (tofu, cheese, soymilk, milk, plus barley for beer) at the top, meats (lamb/mutton, beef, poultry, pork, and farmed shrimp) in the middle, and then the fruits and veggies at the bottom.[6]

Anyone who has shopped at a farmers’ market or subscribed to a CSA understands that fruits and vegetables are in-season at certain times, but with the advent of the supermarket, we haven’t had to pay much attention to when that is. Most veggies are pretty innocuous in all aspects of their carbon footprint, unless you’re talking about supplying them out of season.

“Eating animals in their proper season means eating meat at its best. It encourages more humane, organic farming practices. It also encourages us to think more about the animals that feed us—and hopefully, to appreciate them more.”

Quote credit: [7]

Forcing growth out of season in greenhouses or storing veggies out of season through refrigeration / freezing makes their carbon footprint skyrocket. One British study showed that importing lettuce from Spain had three to eight times lower emissions than growing it locally during the winter.[8] The Swedish study mentioned in last week’s post showed that importing tomatoes from southern Europe required one tenth the energy of growing them locally out of season.[9]

Importing fruit during the winter may be more environmentally friendly than growing them locally or freezing them until you’re ready to use them, but the best option for reducing your carbon footprint is adjusting your consumption to match what is seasonally available. In that way, shopping at local farmers’ markets or subscribing to a CSA helps ensure that you’re buying what is currently in season, nearby. As one food writer noted, “if you eat locally, by default you eat in season.”[10] While I wouldn’t bet money on that in every case, there is a better chance when you buy from a local farm than a supermarket.

Waste Footprint

Unfortunately, as we’ve been spoiled for choice and availability, we’ve also become more comfortable with letting food go bad. (I am no exception, especially when it comes to my record with CSA memberships.) Waste plays a huge role in the supply chain (and the GHG impacts) of our food.

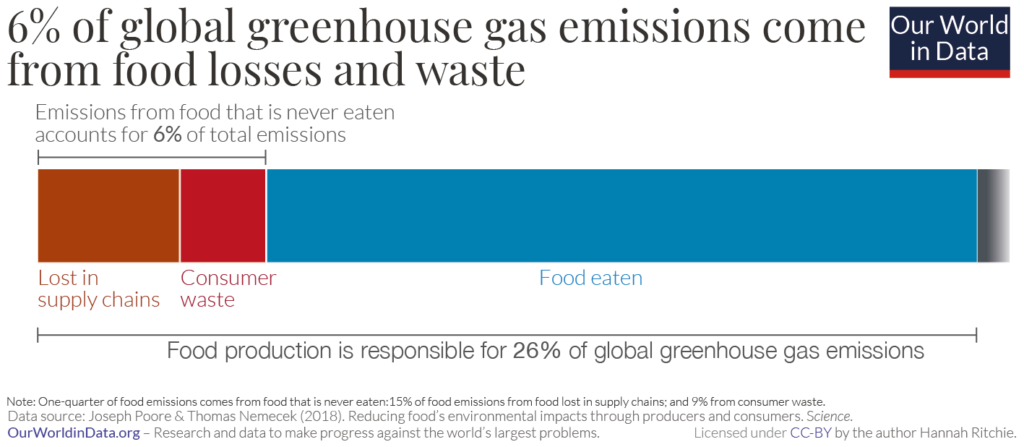

Returning to Our World in Data, we see that 26% of total global greenhouse gas emissions come from food production. Unfortunately, about one quarter of that (6% of the total) is related to food waste. In this context, food waste means spoilage, spills during transportation, or waste by retailers, restaurants, and consumers. All of the land, fuel to run farming equipment, fuel to process, package, and transport the food, and fuel to refrigerate or freeze the food is wasted if the food itself is wasted.[12]

In America alone, we throw away approximately 40 million tons, or $161 billion worth of food every year. We generally buy more than we can eat, and we tend to throw away food before it goes bad because we misunderstand “best by” dates on labels.[13] Food waste makes up 22% of municipal solid waste, and it creates more methane when it breaks down in landfills.

By making more deliberate purchases, buying only food we’re going to eat, we can save money and drastically reduce our food waste. We can also be sure to freeze or give away food that we’re not going to use right away. Composting (rather than throwing out) scraps and spoiled food keeps waste out of the landfill.

For me, getting more food in my CSA than I can reasonably use is probably the biggest down side for me – moreso than being obligated to cook almost every night or getting foods that I hate (like beets). And because food waste is such a huge risk in my kitchen, I’ll leave you with more of a suggestion than a recipe for now…

Last Ditch Effort: Recipe

The biggest casualty of any CSA box that enters my house is definitely the random leafy greens – be they lettuce, spinach, chard, and even cabbage. In the past I have thrown away would-be salad ingredients that were long past their useful life, cursing myself for not getting to them sooner.

Determined not to waste any food this time, I have pulled sad, wilted heads of cabbage and lettuce out of my fridge these past few weeks and put them in the pan instead of the compost. Here you will find a tip and a “recipe” that make good use of these ingredients even after they appear to be gone. (Note: if it’s slimy or moldy, it actually is too far gone – toss it.)

Saved Greens

If they’re not too bad:

To save wilted lettuce (and other greens), place it into an ice water bath for 30 to 60 minutes until it reabsorbs some water and perks up.[14]

If they’re really bad:

For something that is beyond all hope for a salad or sandwich, chop it up and fry it in a pan with some olive oil, onions and/or garlic, season liberally with salt and pepper, and add some cooked pasta.[15] You’ll see in the photo above that I couldn’t resist a sprinkle of parmesan. I like to think that saving the lettuce offset my small cheese indulgence. (I’m sure it didn’t, but that’s what I’m telling myself.)

~

We’re still powering through, trying to use everything before it goes bad, and trying to make room before more arrives. Do you have any success stories of using an ingredient in a creative way before it was truly beyond hope? I’d love to hear about it below.

Thanks for reading!

[1] https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2013/11/seasonal-meat-beef-turkey-thanksgiving/

[2] https://www.imedpub.com/articles/the-effect-of-different-seasons-on-the-milk-quality.pdf

[3] https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/404/404-113/404-113.html

[4] https://www.nature.com/articles/177795b0

[5] https://www.ediblemanhattan.com/topics/food-dining/products-we-love/like-strawberries-eggs-have-a-season-and-its-now-check-out-these-farms-for-those-from-chicken-duck-and-quail/

[6] https://ourworldindata.org/uploads/2020/02/GHG-emissions-by-life-cycle-stage-OurWorldinData-upload.csv

[7] https://www.darcysmeats.ca/2014/02/09/a-guide-to-choosing-your-meat-by-season/

[8] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11367-009-0091-7

[9] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0921800902002616

[10] https://firstwefeast.com/eat/2014/06/high-life-decoded-seasonal-myths-meat

[11] https://ourworldindata.org/food-waste-emissions

[12] https://ourworldindata.org/food-waste-emissions

[13] https://www.rts.com/resources/guides/food-waste-america/

[14] http://www.eatingwell.com/article/291440/you-can-revive-wilted-lettuce-veggies-with-this-simple-trick/

[15] https://spoonuniversity.com/how-to/6-easy-ways-stop-wasting-wilted-greens

1 Comment

Expiration Dates – Radical Moderate · June 6, 2021 at 10:01 am

[…] [4] https://radicalmoderate.online/community-supported-agriculture-part-4/ […]